By Jon Garaffa ’20, Humanities Council

The history of attention is emerging in an interactive computer program called PAN, made using a Rapid Response Magic Grant of the Princeton University Humanities Council. Supported by the David A. Gardner ’69 Magic Fund, Rapid Response Magic Grants bolster humanistic scholarship and community amid social distancing. The new software aims to generate interest in the subjects of history and attention. It presents a flow of primary source texts and images that users can control as historians might.

Leaders D. Graham Burnett ’93, Professor of History, and Izik Alequin, director of Brooklyn-based media startup Post-Traumatic Lab, created PAN to elucidate and dramatize historical shifts in the “attention economy.” The attention economy refers to attention as a limited commodity for which digital technologies compete. Despite the ready availability of information through the Internet, our capacity for processing that data has not increased. As our finite mental resources only allow us to consume so much information at any given time, the latest technologies vie for our eyes and ears.

“People’s experience of archival source material is increasingly mediated by digital technologies,” Burnett explained. “We wanted to try to experiment with interactive media to reproduce the experience of recovering something from the past. PAN isn’t a game, in the sense of something you can win, but it is something you play—ideally like you might play an instrument.”

Burnett and Alequin are pooling their expertise. A professor in the Program in History of Science, Burnett focuses on finding connections among science, technology, and the visual arts. Meanwhile, Alequin, who holds a Master of Fine Arts in Filmmaking from NYU Tisch, founded Post-Traumatic Lab after three years of freelance filmmaking.

In developing PAN, Burnett oversees the project’s historical and conceptual direction. Alequin crafts the user experience and user interface (UX/UI), scripts the engine that runs the project modules, and brainstorms new concepts with Burnett. Julian Chehirian, a PhD candidate in the History of Science who serves as the project’s graduate research assistant, helps to find and categorize source material texts used in the program, and contributes to its art direction.

The team wishes to raise public awareness of the historical process, including as applied to attention. Having studied attention for over a decade, Burnett is convening an international Workshop on Attention at the University this March. He also teaches several classes on the topic, including HIS 490: “The Attention Economy: Historical Perspectives.” In Fall 2018, students in this seminar created a collection of short films on the history of attention and media. Laying the groundwork for their current joint endeavor, Alequin and Burnett recently collaborated with a dozen other artists and filmmakers on a series of short films, “Twelve Theses on Attention,” that emerged out of the 2018 São Paulo Biennial about attention.

Burnett noted that historians can now use search engines to find digitized archival materials from anywhere in the world. This method supplants the traditional technique of locating and analyzing physical archival materials. Accustomed to virtual sources, budding historians will inevitably approach historical inquiry differently than historians of past generations. The project is investigating exactly how so.

“How do young people, who have spent much of their youth in immersive video games, or in rapid visual networks like TikTok, conceptualize the relationship between the past and present?” Burnett asked. “That’s what we are looking to figure out.”

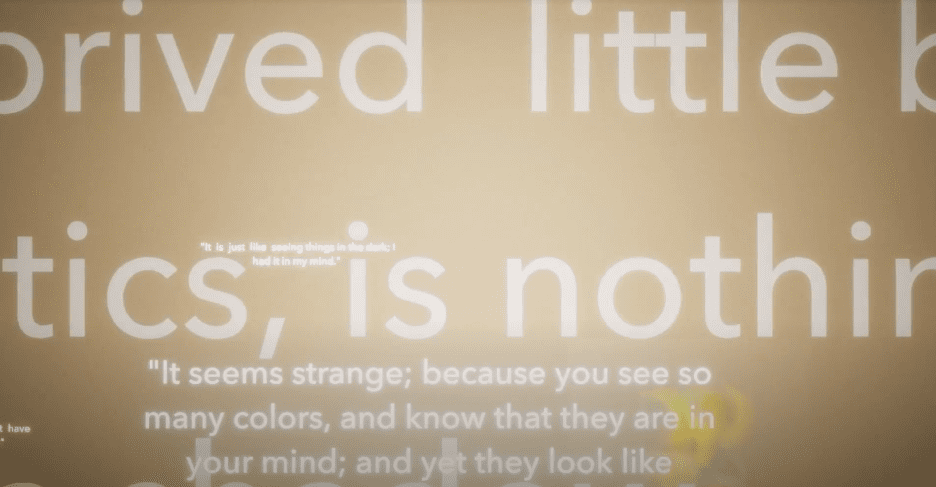

Currently in beta, PAN is an app for phones or tablets. It offers three modules, each dealing with an aspect of the history of attention. One module considers “free-floating attention,” a method in Freudian psychoanalysis that urges a therapist to pay equal attention to all parts of what his or her patient says. A second module covers the twentieth-century “Perky experiments,” in which viewers of an image came to believe that they were only imagining it. A third module, still in development, will examine the history of cursors, such as the bouncing ball above karaoke lyrics. All these modules seek to simulate historical practices of directing attention.

In addition, the modules reveal history through a modern and interactive lens. Burnett described how, in a demo of the Perky module, primary source text fragments flow across the user’s screen. By clicking on the text, the user can slow down the fragments and pull them closer to the user. Unable to keep every text, the user must select some, then work to read them, gradually composing a sense of the larger historical story even while losing much information forever.

“The engine reproduces the central problem that we have specified at the heart of historical inquiry: time sucks things away into oblivion,” Burnett said. “What the historian does is hold things against the flow of time, resisting oblivion for some duration.”

Hence, along with showcasing the topic of attention, PAN helps users understand the efforts historians make to preserve primary sources. The project’s name reflects the poetry and poignancy of historical inquiry, Burnett noted: “Prospectors pan for nuggets in a stream. Cinematographers pan across a landscape to establish a sense of place. The mischief god Pan pipes mysterious tunes of revel and disorientation. We wanted all of that to be in play.”

Through programming PAN, Alequin found great rewards in replicating the experience of a historian. “For me, not being a historian, it has been really interesting to intuit what that experience of being a historian must be like,” he said. “I have to ask myself how I can recreate this experience using the program’s features.”

Burnett and Alequin initially proposed the project as a series of brief documentaries, before deciding to switch to an interactive medium. The change allowed the team to better model time and the archival process, according to Burnett. To challenge traditional, linear notions of time as having a beginning, middle, and end, the engine allows the user to mediate between the present and the past. In real time, users’ actions affect the modules, which revive content from earlier periods in human history.

Furthermore, as opposed to a film, which does not depend on the audience’s input, the software’s output changes based on users’ choices. The options imitate those presented to players in a video game. However, there is no ultimate way to “win” or “beat” the program. Rather, PAN brings new encounters with history into the hands of the digital generation.