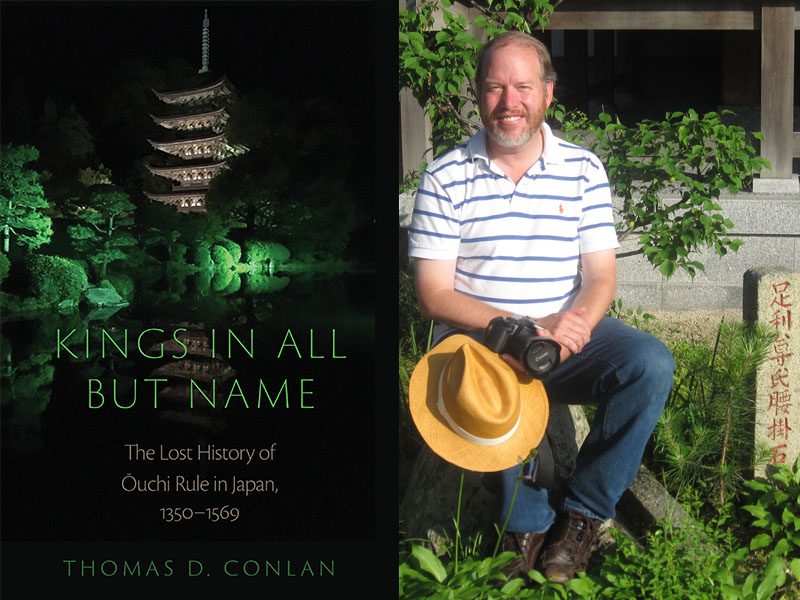

Thomas Conlan is Professor of East Asian Studies and History. His most recent book “Kings in All but Name: The Lost History of Ōuchi Rule in Japan, 1350-1569” was published in January 2024 by Oxford University Press.

How did you get the idea for this project?

During the autumn of 1995, when I was conducting my Ph.D. research on another topic I visited the city of Yamaguchi. At that time, I saw a beautiful five-story pagoda. It was built by members of the Ōuchi family in 1443. I marveled at its size, and the quality of its construction, which was equal if not superior to anything surviving elsewhere in Japan. After seeing it, and the remains of the surrounding town of Yamaguchi, a unique medieval settlement, I realized that Ōuchi were very significant and worthy of research in their own right. I started collecting sources pertaining to them from that time onward but did not start my research on them in earnest until 2011.

How has your project developed or changed throughout the research and writing process?

I originally thought that the Ōuchi were failures. A unique family of warriors who could not adapt to a changing world, and were accordingly destroyed in the mid-sixteenth century. Nevertheless, as my research progressed, I realized that they were innovative figures who promoted new mining techniques, and attempted to possess some of Japan’s major national shrines for their personal interests. Wealthy beyond belief, they oversaw an expansive trading network. In terms of religion, they deified some of their lords, and even attempted to move Japan’s capital to their city of Yamaguchi. In addition, I was surprised to learn that they were Korean immigrants who emphasized their Korean origins, and their ethnicity was widely recognized in both Korea and Japan.

What questions for future investigation has the project sparked?

Over the course of my research, I came to appreciate how Japan’s wealth came from vibrant commerce between Japan, Korea and China. I was surprised to learn that the Ōuchi oversaw innovations in copper smelting techniques in the early fifteenth century. This revolutionary development has been unnoticed because these transformations were not written about in textual sources, but can only be gleaned from archaeological data. I also realized that ancient and medieval Japan and Korea were tightly bound by ties of trade, and the movement of people and I hope to highlight these deep and pervasive exchanges in future work.

Why should people read this book?

All too often “traditional” Japan has been perceived as an isolated, agricultural land at the edge of Asia, but this book reveals a past that we did not know. This monograph will change how you understand Japan and East Asia as it shows that Japan was a multi-ethnic, integrated trading state. The pagoda that so entranced me was recently recognized in the New York Times list of of places to visit in 2024, with Yamaguchi appearing as the #3 destination.