Documentary filmmaking and history combine in The Trenton Project

In April 2018, the city of Trenton will mark the 50th anniversary of violence that followed the assassination of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. To examine the civil unrest through two disciplines, documentary film and history, Woodrow Wilson School Documentary Film Specialist Purcell Carson and History Professor Alison Isenberg are leading an initiative called The Trenton Project.

This public humanities collaboration includes their course, URB 202/HIS 202/HUM 202/VIS 200: “Documentary Film and the City,” in which undergraduates make seven- to 10-minute films that together provide a kaleidoscopic perspective on 1960s Trenton. Carson and Isenberg are developing their own half-hour documentary to unveil next fall, and Isenberg is writing a book.

On Monday, April 9, 2018–the 50th anniversary of the shooting of Harlan Joseph–the public is invited to The Trenton Project Remembers April 9, 1968 to view clips from the documentary film, discuss research findings, and participate in this reframing of Trenton’s history. The course is supported by the Community-Based Learning Initiative and the Princeton-Mellon Initiative in Architecture, Urbanism and the Humanities, and Monday’s event is part of the 1968/2018 Cities on the Edge series sponsored by the Princeton-Mellon Initiative and the Humanities Council.

Uniqueness infuses Carson and Isenberg’s model. Urban history classes rarely include a filmmaking component, according to Isenberg. And community-based filmmaking courses rarely have students tackle different angles of a single topic, said Carson, adding that production opportunities like these seldom extend to inexperienced undergraduates outside film schools.

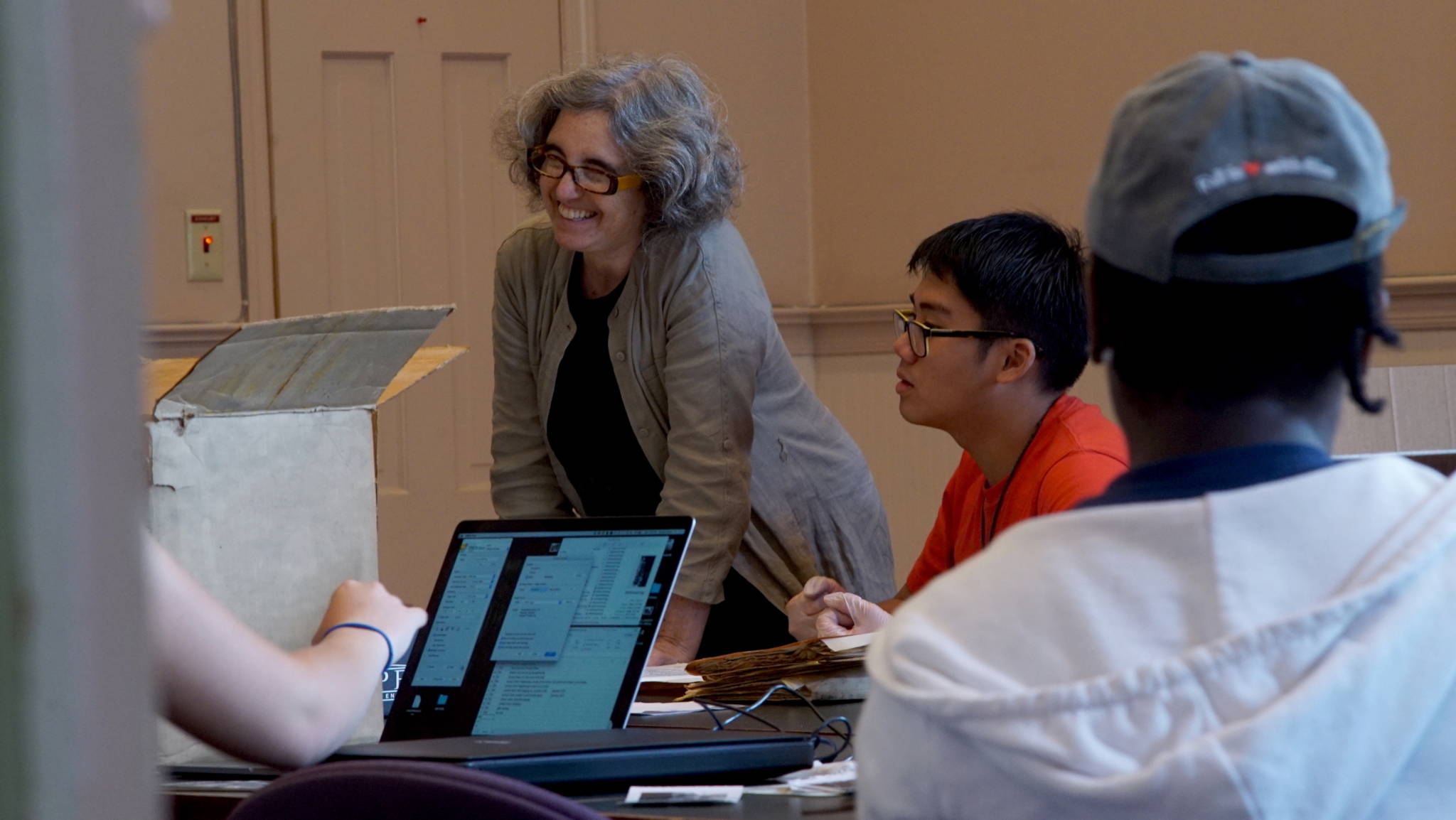

Alison Isenberg working with Princeton and Monclair State University students.

The Trenton Project began as Carson’s brainchild after her 2011 arrival at the University. Given a mandate to connect documentary film with public policy, she consulted the Community-Based Learning Initiative to find cases in which local city dwellers were grappling with issues like housing, employment, and safety. “As a filmmaker, I want myself and my camera to be in the places where these questions are being asked and answered right now,” she said.

Carson proposed the course, which Isenberg, as the new Director of Urban Studies, approved. Cross-listed under Urban Studies and Sociology, it launched in the fall of 2012.

At the same time, Isenberg was teaching HIS 388/URB 388: “Cities and Suburbs in American History.” Each semester, she discussed how historians had long neglected the wave of violence that shook hundreds of communities across the country after Dr. King’s death.

In November 2014, protests about the non-indictment of white police officer Darren Wilson, who had fatally shot Michael Brown, a black teenager in Ferguson, Missouri, boosted student interest in the 1968 civil disturbances. She felt compelled to investigate a puzzling case that she had presented for a dozen years as ripe for research: a New York Times report that during Trenton’s unrest, police shot college student Harlan Joseph for allegedly looting.

Isenberg learned that nobody had seriously researched him or the Trenton riots. Meanwhile, as Carson interviewed Trenton residents for The Trenton Project, they kept referencing the impact of the riots. Since Isenberg always attended Carson’s student-film screenings, conversations between the two revealed the intersection of their findings.

“We began to see that Harlan Joseph’s story was key to understanding what was regarded as a turning point for the community of Trenton, but had not been explored,” Isenberg said.

They decided to revamp The Trenton Project. The pair would make a film together. In addition, they would co-teach Carson’s course, moving it from Sociology to History by focusing on the 1960s in the fall 2016 and 2017 semesters. They have also organized several summer research workshops for undergraduates and graduate students.

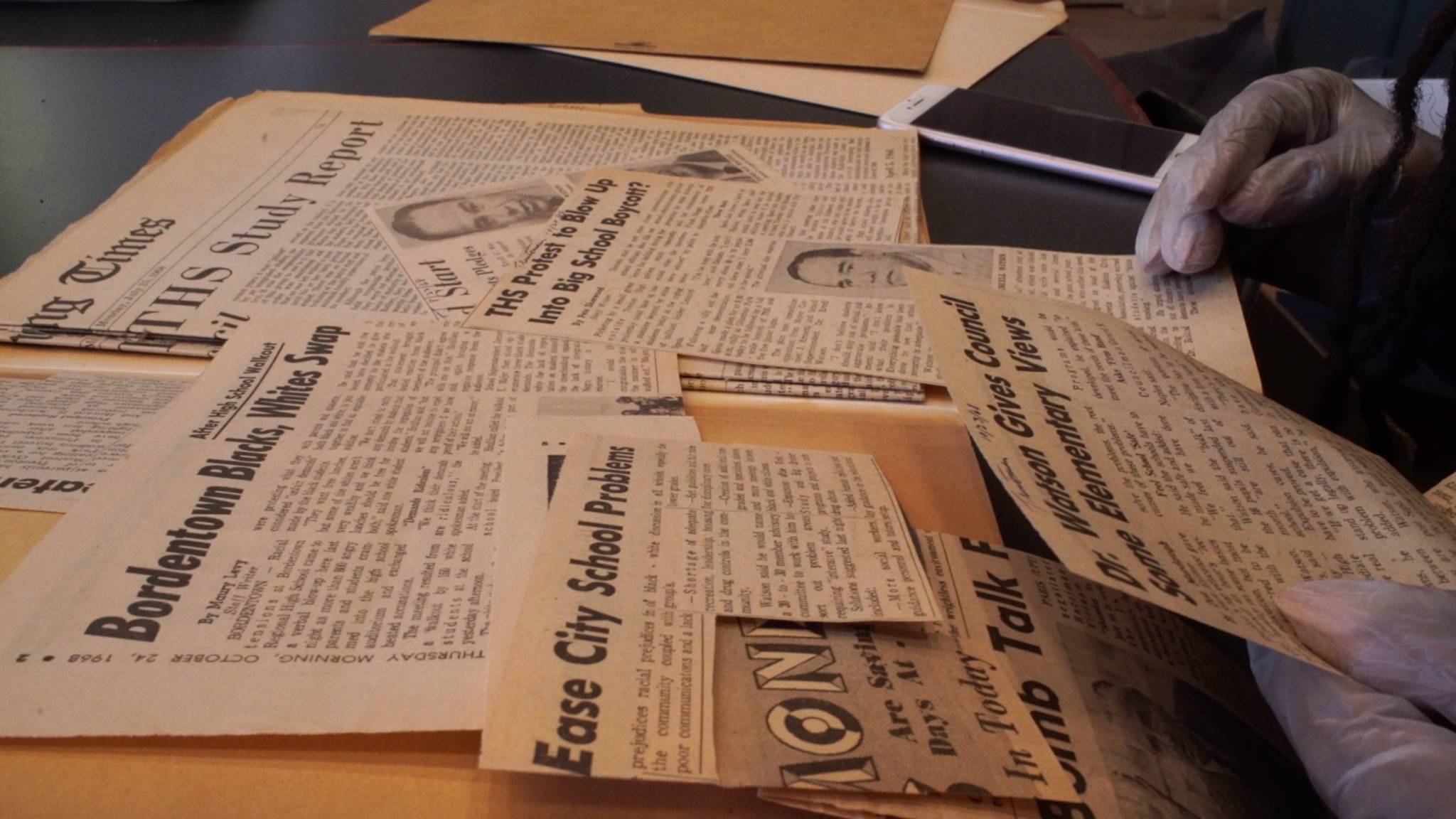

1960s records found in the attic and basement at Mercer Street Friends in Trenton. (Photo: Purcell Carson)

The interplay of documentary filmmaking and history has enlightened both instructors. According to Isenberg, the collaboration and student involvement has accelerated the scholarly process by intensifying and multiplying the amount of research accomplished in the past three years. Furthermore, whereas a historian might take 10 years to complete a book, a student video requires only four months, she said.

“The biggest challenge of writing a book is controlling the research, and then making it accessible and understandable so that people will want to read it as a story, and still satisfy what you see as the complexity of the story,” Isenberg explained.

Carson said that teaming up with Isenberg has taught her so much about how to conduct historical research, since few filmmakers have the time, budget, space, and schedule to dive deeply into a topic. For her part, Carson specializes in distilling the essentials.

“I come with a much more journalistic focus, where I’m driven by what people tell me. I talk to people, take what they say, and report that back. For this project, I’m also driven by the poetics, ethics, and visual representation of memory. In the end, what we’re trying to make is a work of art,” she said. Toward these ends, often with the students, they have interviewed nearly 60 people.

The grammar of film demands the elimination of explicit scholarly analysis, so cultural context, like socioeconomic background, must be shown through the experiences of characters, Carson explained. She gave the example of how changing racial demographics at Trenton High School spurred school violence, which spilled into the streets as students made demands on city hall. The tightness of cinematic narratives focuses the research, and produces not only an intellectual but also an emotional impact on the audience, more so than in written history.

Isenberg highlighted another emotional impact on the interviewees in documentary filmmaking, unlike in conventional oral history: The Trenton Project marks the first time that her interviews have played a therapeutic role.

“History is about memory, and people’s memories are not just of happy things. They’re of traumatic events. We keep going over traumatic things that happen to us individually and collectively as a way of exploring and dealing with them,” Carson said. Filmmakers always push subjects to articulate their feelings, whereas academics might resist doing so, she added.

Carson said she benefits more from the collaboration than she would from a solo project, for two people push each other to accomplish more.

“I did not realize when we decided to co-teach that it would be more work than doing it on my own. In a really good way, everything that we’re doing is a conversation,” she noted.

Isenberg echoed that she learns extensively from her colleague’s different approaches. For instance, Carson’s description of the editing process in film was far more interventionist than a typical historian’s editing methods. And analyzing filmed interviews is a completely different experience from handling a transcribed audio interview of the exact same conversation. The filmed interviews incorporate body language, facial expressions, voice characteristics, tone, mood, social interactions, and background settings—literally, entirely new human dimensions.

Students learn to conduct an on-the-street interview as Calvin Thomas gives them a tour of his old neighborhood on Kelsey Avenue (Photo: Michael Hotchkiss)

The public student-film screenings at ArtWorks in Trenton and the Arts Council of Princeton, each attended by 120 or so guests, have already started affecting how people discuss Trenton’s 1968 civil unrest, according to Isenberg. Further strengthening the ties between Trenton and Princeton was the team’s discovery early on that Joseph spent six weeks in a summer program for high-school sophomores at the University in 1964–a prototype of the national Upward Bound program. The Trenton Project faculty and students have interviewed some of Joseph’s classmates, three of whom also later graduated from the University. In the mid-1960s, Princeton undergraduates worked as counselors in the summer program, adding yet another perspective.

While the course draws undergraduates already interested in social justice, Carson said, she likes to think that those who enroll for the sake of making videos learn that documentary filmmaking has many social implications. She added that The Trenton Project has helped students shape their worldviews, so as to better understand the backdrop and influence of their actions. For example, Emmy Bender ’19 was editing her film about a 1963 civil-rights march in Trenton during the same weekend she participated in a women’s march, and told the class how meaningful that coincidence was.

Isenberg said she hopes that the collaboration, including the large archive of primary source materials and interviews that she and Carson have created, will inspire others to research the history of cities like Trenton, starting from important moments like Joseph’s death. They will be able to use only a small fraction of the evidence collected.

“To be able to factually revisit what happened that night and how it unfolded is an example where historical research can make a concrete contribution to current conversations about Trenton’s future,” Isenberg said. “I would like this work to address some misconceptions about the city in 1968 and create just enough space for new stories about the past to take hold. We can’t know where those stories are going to take people. But Harlan Joseph’s life, on its own terms, is an inspiring and empowering example.”

By Ruby Shao ’17