By Ruby Marie Marsh ’17

To launch each academic year, the Humanities Council invites the University community to a wide-ranging discussion of central issues in research and teaching. The 16th Annual Colloquium, “Humanities and/as Choice,” took place Thursday, September 8 at 4:30 pm in the Chancellor Green Rotunda.

Humanities Council Acting Chair Tera Hunter (History, African American Studies) welcomed the large crowd to the first in-person Colloquium since 2019. “How is the concept of choice conceived differently across time and space in ways that we might find very jarring for our own time?,” Hunter asked. “What are the moral, political, social, and economic imperatives that determine the possibilities or disabilities of choice? What roles do obligations and duties play in how choice is conceived?”

Four University professors spoke on their fields of study in relation to the theme, framing the interdisciplinary dialogue.

“The Government of Choice and/as Values”

Opening the conversation, Catherine Clune-Taylor (Gender and Sexuality Studies) recounted that her research on intersex people raised questions requiring both the sciences and the humanities to answer.

“For science is itself a human practice, value-laden throughout, from the questions we ask and the ones we don’t, the distinctions made between signal and noise, the interpretations of data we give, to the applications or conclusions that we derive from our results,” she said. She added that science is not objective in the sense of being unbiased, value-free, or apolitical.

Invoking Michel Foucault’s usage of “to govern” to mean “to control the possible field of action of others” in Security, Territory, Population, Clune-Taylor lamented the present state of affairs.

“The government of gender and sexuality in this country is currently such that it is hard for many of us to make all of the big and little choices that shape and give color and texture to our lives—grindingly, exhaustingly, and heartbreakingly hard,” she said.

“Conversion During the Seventh Crusade: An Episode in the Social History of Choice and Decision”

William Chester Jordan (History) delved into the reign of King Louis IX of France, canonized partly because of his dedication to spreading Catholicism. The monarch refused to force people to accept the faith. “Conversion was a choice,” Jordan said.

According to Jordan, the king both supported granting freedom to Muslim slaves who converted and supplied them alms. His officials also promised additional monetary gifts, lifelong pensions for heads of households, housing, and settlement in France for the converts.

Medieval Christians and Muslims would not have considered the king’s offering of gifts coercion, and no evidence indicates that the king would have retaliated against people for refusing his offer, Jordan said. Nonetheless, Jordan wondered if the potential converts felt implicitly threatened, since remaining Muslim might consign them to perils, such as expulsion from the Crusader states to their dangerous borderlands.

“If vulnerable people feared that regional violence might target them, deliberately or fortuitously, and if the king offered them succor at the price of conversion, did this genuinely meet the threshold of free choice?” he inquired.

“Buddhism, Confucianism, Choice?”

Next, when discussing specific Asian traditions, Stephen F. Teiser (Religion) argued, “Choice as a theoretical framework may be based on assumptions about agency and equality that are historically specific and not human universals.”

He noted that medieval Chinese Buddhists and Confucian thinkers generally distinguished three orders of ethically significant others: parents or other “social seniors” like teachers or benevolent rulers; saints or “religious superiors”; and the poor or “material inferiors.” Each order bestows, upon every person, a distinctive gift that generates a distinctive obligation.

On this model, social seniors provide care, which ought to elicit undying obedience and support from its recipients. A person should repay saints for exemplifying wisdom and compassion by contributing to their religious institutions. In response to the poor, who just by existing inspire opportunities for philanthropy and reflections on karma, a person should promote secular good causes like public housing, Teiser said.

He explained that, whereas some concepts of choice presuppose a world of free agents understood as equals, Buddhism features few, if any, relations among equals. Rather, asymmetrical imperatives direct interactions.

“The Choice that Is No Choice: Involuntary Martyrs and the Martyr Complex”

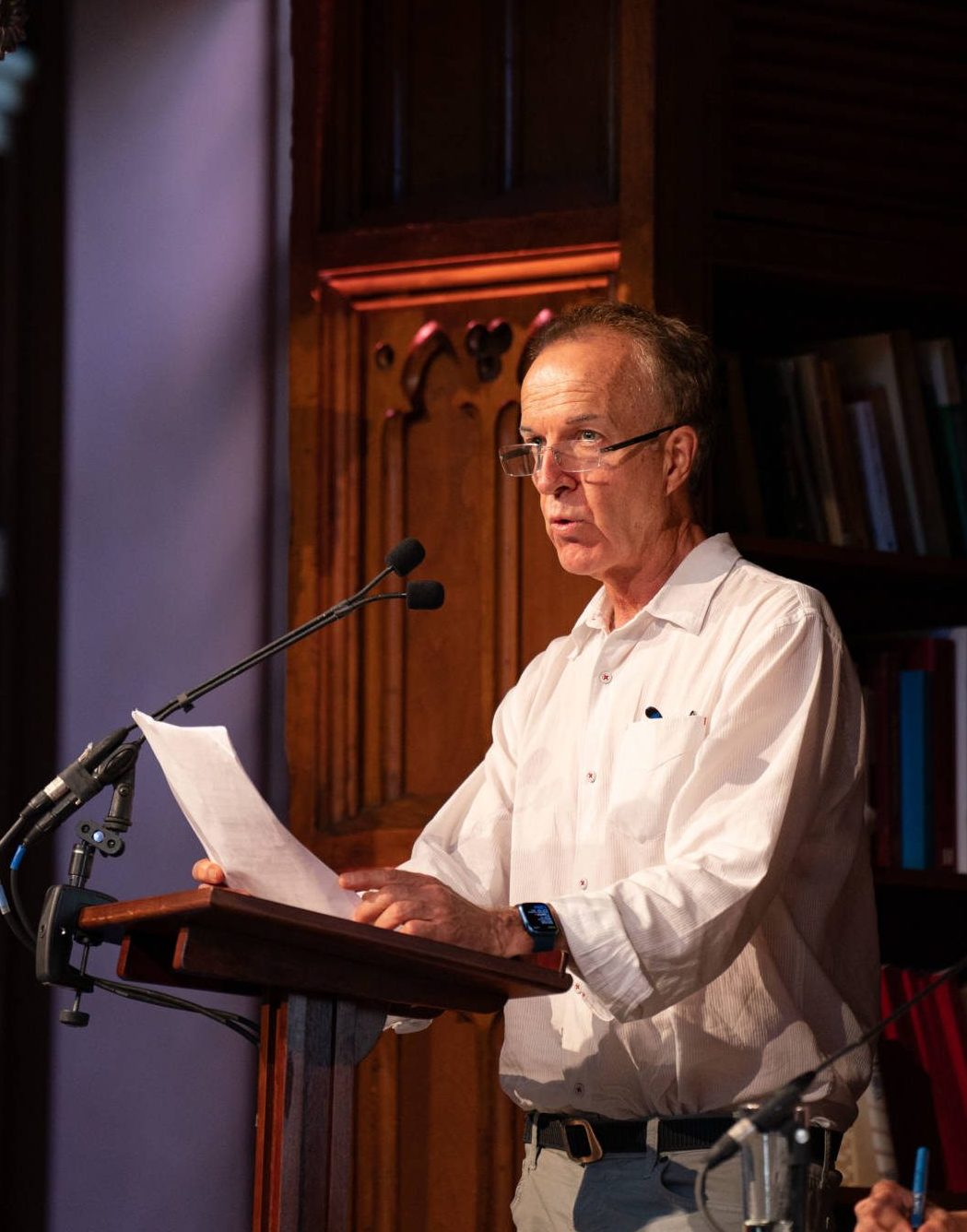

Concluding the panel with a return to the present, Rob Nixon (English, High Meadows Environmental Institute) focused on what he called the 21st-century surge in environmental martyrs, meaning those assassinated for green activism.

He gave the example of Nigerian activist Ken Saro-Wiwa, who advocated for the mangrove forests in the Niger Delta, and for the people who depended on those natural resources. Nixon quoted Saro-Wiwa: “When the land is ravaged, when streams choke with pollution, silence would be treason.”

Military, corporate, and authoritarian powers frequently depict environmental martyrs as having chosen self-slaughter, according to Nixon. He articulated a common message from those trying to suppress protests: “If you choose to continue to voice dissent, you are in effect electing to die, leaving us no choice but to eliminate you.”

He identified Saro-Wiwa, along with environmental activists Chico Mendes and Berta Cáceres, and, in the realm of social justice more broadly, the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., as among hundreds posthumously defamed by their persecutors for choosing to die. Yet forsaking their highest ideals never represented a viable alternative, Nixon noted. “All these figures were martyred after being confronted with a choice that was no choice,” he said.

For upcoming humanities events, visit the Humanities Council website.