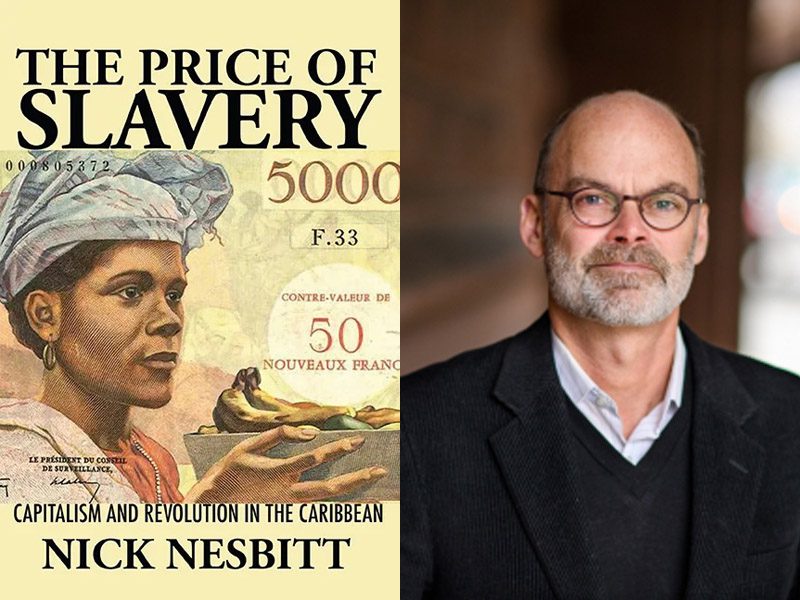

Nick Nesbitt is Professor of French and Italian. His book “The Price of Slavery: Capitalism and Revolution in the Caribbean” was published on March 18, 2022 by University of Virginia Press.

How did you get the idea for this project?

I was originally inspired by the striking lack of theoretical clarity on the nature of capitalist slavery that one finds in the literature since Eric Williams’ classic 1944 study “Capitalism and Slavery,” including most recently the so-called “New History of Capitalism.” One way to understand the book is thus as a theoretical intervention in current debates on slavery and racial capitalism such as the NHC or the New York Times’ 1619 Project. Focusing on capitalist slavery in the Caribbean, the book argues that only by returning to Marx’s analysis of capitalism is it possible adequately to grasp the nature of capitalist slavery as a social phenomenon—returning to Marx as did each of the Caribbean thinkers I also discuss: CLR James, Aimé and Suzanne Césaire, Jacques Stephen Alexis. At its most fundamental level, the book seeks to bring into question the historically contingent form of social relations in which we live: i.e., capitalism. I argue that the development and deployment of racial ideologies and capitalist production processes (including slavery) necessarily occurs within a governing framework of social relations, which Marx called and analyzed as the capitalist “social form.”

How has your project developed or changed throughout the research and writing process?

I’ve come away from this book project with a deepened understanding and appreciation of the essential nature of capitalism both in theoretical terms and as a historically specific phenomenon, as well as the fundamental place of slavery within it. I’ve also become ever more appreciative of the importance of Marx’s analysis of capitalism for the Caribbean thought and more generally, of the extraordinary and contemporary genius of Marx’s unfinished masterpiece, Capital.

What questions for future investigation has the project sparked?

This spring, I am finishing a book on the (often unspoken or implicit) ways Louis Althusser’s brilliant students—Pierre Macherey, Alain Badiou, and Etienne Balibar—have continued their initial Spinozist, anti-Hegelian project of “reading Capital” (1965) in the decades since the publication of the famous book by that name. This project follows directly from this one as well as from a book I previously edited (“Reading Capital Today”); above all, it again gives me the challenge and pleasure of thinking not only with Marx and the Althusserians, but with Spinoza, in my view the greatest philosopher of the modern world and (human) existence tout court. Spinoza is, among many things, the inventor of ideology critique and of the critique of the illusory nature of unreflected lived experience, of the systematic critique of racism and antisemitism, and is above all a thinker who did not merely take a stand against all the violence, injustice, and illusions of his world, as have so many others, but who in response developed in his most extraordinary work, the Ethics, the means to understand and to overcome the infinitely varied forms of illusion and injustice to which we naturally remain subject. Spinoza’s thought, to an unparallelled degree, invents and deploys a powerful critical methodology, one that challenges us to develop our capacities for thought and freedom to their utmost degree.

Why should people read this book?

I’m increasingly convinced that our immediate lived experience of violence and oppression is insufficient in itself to orient adequate forms of critique and response to that injustice. The lesson I take from the great thinkers of the black radical tradition–Toussaint Louverture, Vastey, WEB Dubois, Aimé Césaire, Suzanne Césaire, CLR James, Frantz Fanon, and so many others–is to seek out and appropriate whatever theoretical tools can be found lying around, and to critically adapt them to our own needs and situation. Whether the French Jacobin or African Mande Declarations of Human Rights, Hegel, Spinoza, Marx, or any other penetrating resource, there can be no arbitrary limits, racial or otherwise, to the materials of critical thought. Amid the current proliferation of fake news, the post-Trump racist malaise and democratic dysfunction, and the abysmal predominance of social media as worldview producer, to undertake such a close, postcolonial reading of Marx’s Capital and its Caribbean resonances–such as I undertake in the book–has the further benefit of giving the reader (and here I include myself) an understanding of what it means irrefutably to prove a claim (in this case, the essential nature of capitalist slavery). Marx did not simply voice “viewpoints,” and “perspectives.” In Capital, he carefully shows the reader, step by step, point by point, what must be the essential nature of any society that is characterized by the general predominance of commodities and commodified social relations, including capitalist slavery itself.

Learn more about other publications by Princeton University faculty in the humanities by exploring our Faculty Bookshelf.