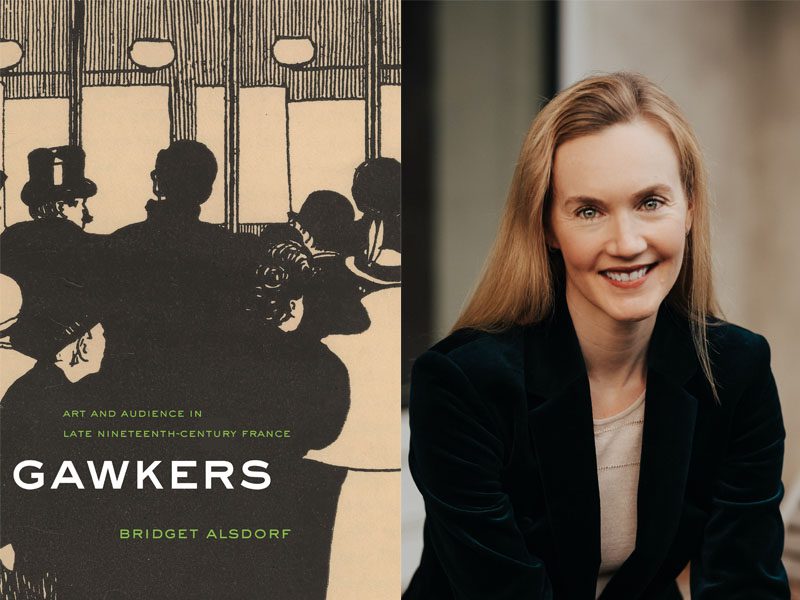

Bridget Alsdorf is Associate Professor of Art and Archaeology. Her book “Gawkers: Art and Audience in Late Nineteenth-Century France” was published on March 1, 2022 by Princeton University Press.

How did you get the idea for this project?

It happened in the National Gallery of Art. I was writing the conclusion to my dissertation, which would become my first book, “Fellow Men: Fantin-Latour and the Problem of the Group in Nineteenth-Century French Painting,” and I was trying to articulate the differences between groups and crowds. This was my excuse to head to the museum. I asked to see some crowd scenes, including a stunning little woodcut by Félix Vallotton titled The Paris Crowd (1892). It flooded me with ideas about how visual art is uniquely capable of capturing the psychology of crowds. It remains a favorite – we have an impression of it in our campus museum – and it’s the artwork described on the first page of “Gawkers.” I didn’t know it at the time, but there was a whole book in that picture.

How has your project developed or changed throughout the research and writing process?

After a while, I realized that the crowds I was studying, in pictures and in texts, often revolved around a category of people the French call les badauds. “Gawkers” is the closest translation of this term for people struck by the sight of something, caught in a state of aesthetic and ethical paralysis. Vallotton put gawkers in almost all of his street scenes, and so did many of his models and peers: artists like Daumier, Degas, Gérôme, Toulouse-Lautrec, and Bonnard; writers like Maupassant and Mallarmé; and the filmmakers Auguste and Louis Lumière. All of them saw gawkers as a symptom of modern urban culture, and many of them worried over the similarities between gawking and looking at art. It became clear that the book had to focus on this – a conflicted model of modern subjectivity more expansive and less heroic than the far more studied flâneur.

What questions for future investigation has the project sparked?

There are historical and cultural circumstances that made nineteenth-century France, and especially Paris, a center for gawkers and their theorization, especially as a counterpoint to the masculine, bourgeois, individual flâneur, and writers at the time often emphasized the Frenchness of gawking as a pastime; but gawking is obviously not unique to the French. I hope this book will lead others to study this mode of looking in other historical, cultural, and transcultural contexts, and to think more comparatively about the social and aesthetic experience of the city that it suggests. Following in others’ footsteps, this book is also an effort to integrate the history of early cinema and the history of paintings and prints. We have only scratched the surface of the complex interplay between these media and their audiences, and I hope to pursue this further in my next book on Scandinavian art.

Why should people read this book?

All of us are gawkers, at least from time to time. This book gives that human inclination a history, told with an array of captivating and thought-provoking art. These artists were more than skilled technicians and self-promoters. They were social philosophers with a keen understanding of cultural politics, and they were navigating a politically polarized, highly mediatized society with striking similarities to our own. They have a lot to teach us about the blurred lines between art and entertainment; about the ethics of art, journalism, and social media as sites of passive and anonymous mass looking; and about ourselves as reactive visual creatures and consumers of culture. They also knew how to hook an audience.

Learn more about other publications by Princeton University faculty in the humanities by exploring our Faculty Bookshelf.