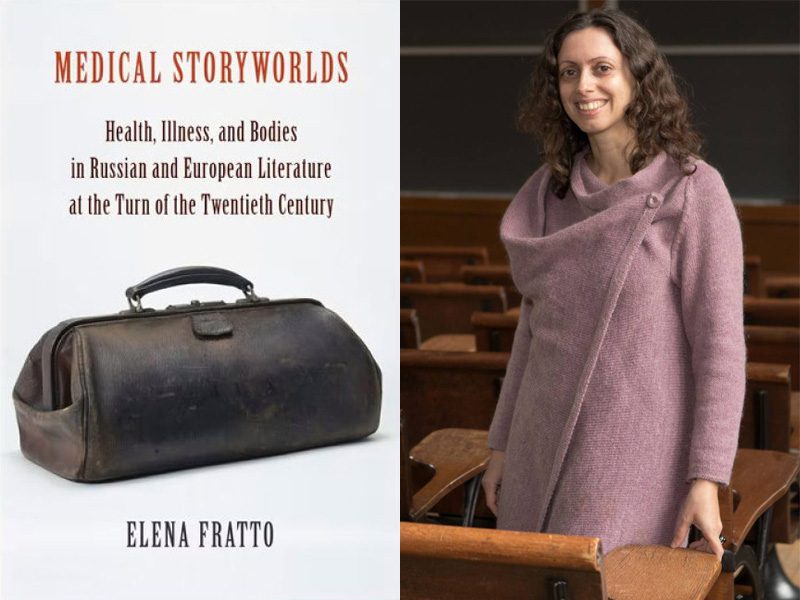

Elena Fratto is Assistant Professor of Slavic Languages and Literatures. She has received Humanities Council Magic Grants for Innovation to develop team-taught medical humanities courses and a working group, “Bodies of Knowledge.” Her book “Medical Storyworlds: Health, Illness, and Bodies in Russian and European Literature at the Turn of the Twentieth Century” was published November 2, 2021, by Columbia University Press.

How did you get the idea for this project?

I stumbled upon the interpretive nature of medicine when I arrived in the United States from Europe and encountered a healthcare system that was profoundly different from the one I was used to. A narrative-theory enthusiast, I decided to map the field with my toolbox of concepts and definitions—plot, authorship, agency, text—in order to parse it. While literary scholars had traditionally approached storytelling in medicine by focusing mostly on psychoanalysis and psychology, I set off to reveal and examine the narrative structure of medical practice in general, as a set of protocols and procedures, of medical knowledge in its formulation and transmission, and of public health endeavors.

How has your project developed or changed throughout the research and writing process?

I was writing the conclusions when the Covid-19 pandemic broke out and changed our priorities and our everyday lives profoundly, exacerbating existing trends and revealing deep-seated values in powerful ways in every society it affected. Before the manuscript went into production, I felt compelled to compose an afterword that staged the pandemic as a signifier and an excellent case study—current, tangible, familiar to the readers—that would illustrate the points articulated in the book chapters.

What questions for future investigation has the project sparked?

As the ongoing pandemic has made us realize, there is no doubt that health and healthcare are global phenomena. The medical humanities have been somewhat slow in acknowledging the planetary scale of its traditional questions and concerns. The field is still overwhelmingly Anglophone in scope and would benefit immensely from different cultural perspectives. As a Slavist and comparatist, I introduce texts that belong to my fields of expertise, and I hope that other non-Anglophone traditions will soon be brought into the conversation as well. The cross-disciplinary and transhistorical interconnections that this book highlights encourage and lay the groundwork for more research informed by such a methodological approach in other cultural traditions. Moreover, other core concepts in the medical humanities besides the ones I addressed in this book, such as caregiving and disability, could be examined fruitfully with the same methodology. Finally, the farther I ventured into this project, the clearer it became that health and the environment are inextricable. In “Medical Storyworlds” I did not have the opportunity to introduce the “environment” broadly intended—physical and natural, but also the social and economic environment, value systems and the circulation of goods and knowledge. My current book project, “Metabolic Modernities,” will examine precisely that rich area by focusing on energy transformation and exchanges across the human-nonhuman divide in Russia at the turn of the twentieth century.

Why should people read this book?

While this book is relevant to the fields of literary studies and the medical humanities, it also reaches far beyond those two scholarly fields and the academic arena altogether. By zeroing in on storytelling techniques, we can lay bare the plots and tropes that shape and inform our experience of illness, treatment, or caregiving. Moreover, the book shows how texts written one century ago or longer, likely beyond the intentions of their authors and their cultural horizons, make fundamental contributions to current major debates in the medical humanities, such as end of life, the notion of “risk” and preventive medicine, biopolitics and public health, and the nonhuman entities or human-made devices we host in our bodies. By the same token, an approach to canonical, “dusty” literary works that is informed by questions from the medical humanities yields new interpretive avenues into those well-known texts.

Learn more about other publications by Princeton University faculty in the humanities by exploring our Faculty Bookshelf.