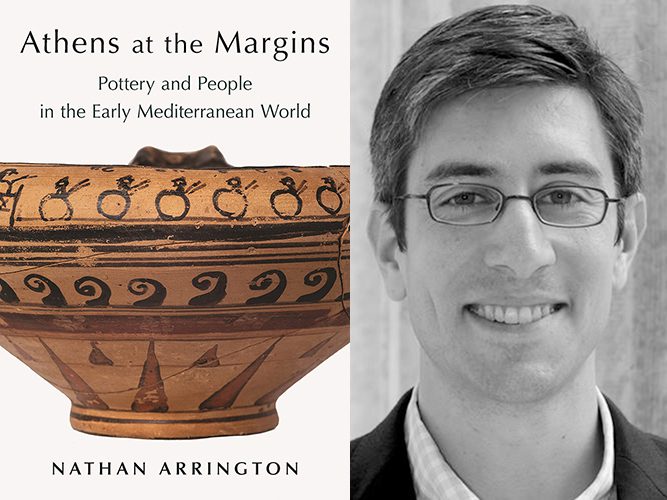

Nathan T. Arrington is Associate Professor of Art and Archaeology and Director of the Program in Archaeology. His book “Athens at the Margins: Pottery and People in the Early Mediterranean World” will be published in October 2021 by Princeton University Press.

How did you get the idea for this project?

Historians and archaeologists often talk about cultural change occurring at the top of the social ladder and trickling down. We tend to think that it is the elite who engage in a practice, or use a set of objects, or develop a style. Everyone else imitates them, until eventually the elite need to find new ways to distinguish themselves. I found this model increasingly problematic, and I wanted to examine possible alternatives. A strength of archaeology as a discipline is that it encompasses a wide array of material evidence, not just high art, but our models of change tend to be very one-sided. Might the social margins have made meaningful and lasting contributions to cultural change? And if so, how? I wanted to explore this question in a time period when artistic styles were rapidly evolving and where I could examine the question from a cross-cultural, trans-Mediterranean perspective.

How has your project developed or changed throughout the research and writing process?

Like many writers, I had to both narrow and expand my topic in the process of writing the book. I decided to focus on Athens in the 7th-century B.C. because there is abundant material evidence and it has played a critical role in the stories that we tell about Greece. With Athens and its wider territory, I could look closely at archaeological contexts that provided a chronological framework to my argument. It was possible to explore the role of artists, immigrants, soldiers, and other types of individuals who used a remarkable style of pottery that does not look like what most museum-goers would expect from Greek art. In terms of expansion, the book ended up looking at the different types of communities that were formed at this time. Classicists tend to focus exclusively on the polis (city-state), but there were other social configurations that formed in and through the use of objects. I found that the lens of subjectivity was a very useful way to think about the interaction between individuals and objects while also retaining a formative role for larger social groups. Finally, while Classicists emphasize the role of the Near East on Greece in this time period, I was increasingly finding more evidence for Italian and other western connections, forcing me to adopt a more open, networked model of movement and interaction.

What questions for future investigation has the project sparked?

In the broadest terms, the book offers a challenge to scholars to consider the formative potential of the margins as they existed in the past and as they have been constructed by historiography—that is, what have we left out of stories, and why? In archaeology and art history, canons are created over centuries in a process that requires some critical examination. In addition, I have found that this book opens up some specific questions about the conditions of artistic production in ancient Greece. How artists worked in terms of their relationships to patrons, to workshops, and to craft networks needs to be explored at greater length.

Why should people read this book?

If for no other reason, people should pick up this book to look at the pictures! A visual argument takes place over the course of the images. When people think of Greek art, monuments of the Classical style (5th–4th centuries B.C.) often come to mind, like the Parthenon. This book will show them something very different, which should provoke some questions, such as: why do these objects look this way, why does style change, and how might it matter? The book ultimately turns the main explanation of the time period, the so-called “Orientalizing” phenomenon, upside down. While change was thought to occur from the top down under the influence of the Near East, the book shows the dynamic role of the social and geographic margins in a networked Mediterranean where goods and ideas could move in unexpected directions.

Learn more about other publications by Princeton University faculty in the humanities by exploring our Faculty Bookshelf.