By Catie Crandell, Humanities Council

“Surely, we’ve had the best online poster,” joked Nigel Smith, Professor of English and Chair of Renaissance and Early Modern Studies. The poster in question features a vibrant pair of monsters: one a ghostly white giant squid or cuttlefish, beak open, illuminated against a violet sea, the other, an ornate green dragon chomping on the leg of a toad whose mouth spurts blood. These two images and the poster they appeared on announced a pair of papers on early modern monsters delivered by Surekha Davies (Utrecht University) and Jennifer Rampling (History of Science). Rather than focusing on what might be frightening or otherworldly, these two scholars offered arguments that use the monstrous as a tool for better understanding early modern and renaissance perspectives on the natural world.

Watch the video of the talk here.

Davies, whose paper was titled “Life on the Edge: Imaginative Prototyping and Sea Monsters in Early Modern Europe,” opened with a provocative question: “How do you chart life at the edge of the world?” Much more than a catalogue of sea monsters, Davies’s talk explored how “making knowledge of the places that we cannot access with our bodies requires deliberate imagination.” These remarks, accompanied by an engaging set of maps and other images, called for recognition of who we are in time and place compared to the time and place we are attempting to understand so as to avoid “strong gaslighting of visual imagery”. For example, contemporary viewers examining a 16th-century map need to recognize several material factors before deeming one of the creatures featured in the map as mythical or imaginary. As Davies pointed out of the 16th century, even those with the most experience of the sea, such as sailors, would only have had fleeting and partial experience of deep-sea creatures such as whales. People faced with the rare opportunity to view a whale in its entirety because it became beached were more likely to have viewed “decayed and half-eaten specimens” that required a kind of forensic gaze. Then there is a secondary challenge of transmitting the most accurate knowledge of these animals to the woodcutters creating the maps, and also the limitations of that visual medium. “We need to think about questions that don’t revolve around the extent to which an image looks like a photograph,” stated Davies. Reframing monstrosity is one of the ways to interrogate “our own modernity and the periods that we think of as premodern.”

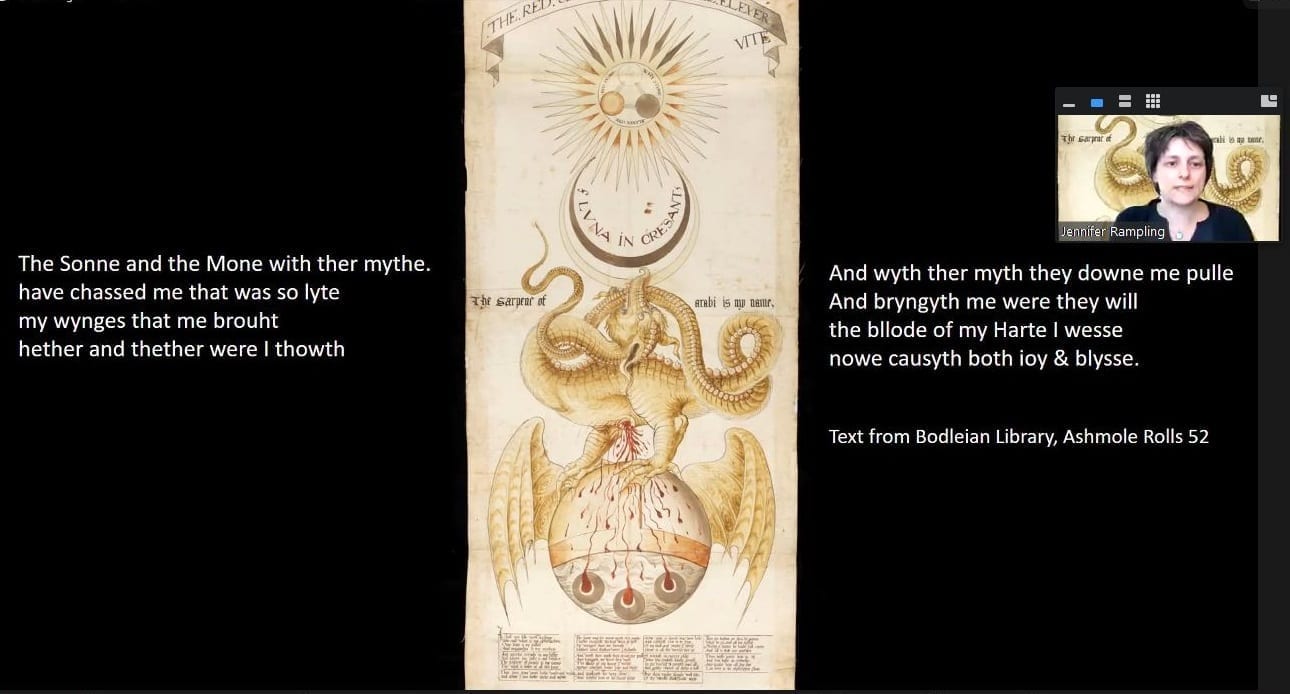

Rampling, whose paper was titled “Deciphering the Dragon: Monsters and Image-Making in English Alchemy,” delved into the allegorical rules that fantastical creatures played in illustrating alchemical texts. In considering these illustrations, Rampling asked “What do they offer more than the text itself?” Naturalistic illustration, as she pointed out, might not actually be able to capture the qualities and distinctive properties of a substance. Consider, for instance, mercury; it could be illustrated as a container with a liquid in it but that tells the viewer very little. Instead, allegories prove much more effective. Visual metaphors provide much more information: “birds and feathers suggest volatility, solvents are often depicted with carnivorous beasts,” observed Rampling, who explained several different illustrations of mercury, which is primarily associated with its ability to dissolve silver and gold. In one image from an early 15th-century book Buch das heiligen Dreifaltigkeit (Book of the Holy Trinity), mercury is represented by a “serpent tailed female figure piercing Adam and Eve with a lance.” In another case, mercury becomes a “star-headed, snake-tailed creature decapitating gold and silver.” As Rampling explains, “In these images, the beasts are doing something specific, they have a job. Their sense can be appreciated, which is why these images remain relatively consistent as they are copied.” Where the dragon stands for the dissolution of metals, the basilisk “stands in for the fixation of mercury” due to the monster’s deadly gaze. Learning how to read these images allows us to understand “the problem of discussing chemical reactions in the period.”

The next Renaissance and Early Modern Studies workshop will take place on May 12 at noon, with Dimitri Levitin (All Souls College, Oxford) presenting a paper on Pierre Bayle’s claims about the possibility of a society of virtuous atheists.