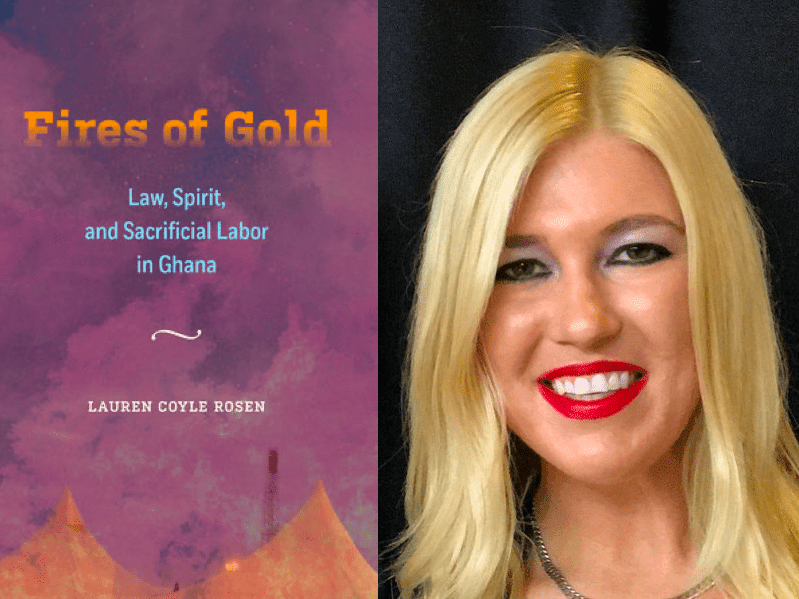

Lauren Coyle Rosen is Assistant Professor of Anthropology. Her book “Fires of Gold: Law, Spirit, and Sacrificial Labor in Ghana” was published by University of California Press in April 2020. This retrospective Q&A is part of an effort to acknowledge all the wonderful books published early in the pandemic.

How did you get the idea for this project?

I have long been fascinated by the oft-hidden dimensions of law, economy, and sovereign power, particularly in postcolonial settings, as well as by the roles that spiritual forces and symbolic authority play in the perpetual crafting of social worlds. The social worlds surrounding gold mining in contemporary Ghana are particularly powerful prisms for studying and theorizing transformations in these domains. Mining is the site of the most intense and often violent conflict today in Ghana, which is one of Africa’s most celebrated democracies. The nation is now also the largest gold producer in Africa.

I first was drawn to the gold fields on account of the completely fascinating legal and political complexities of the conflicts. I had encountered them while doing research work one summer with an environmental justice organization based in Accra, Ghana’s capital. Through the unfolding of many fortunate encounters, I got to know multiple people who were involved in organizing efforts in Obuasi, Ghana, which is the legendary mining town at the center of Fires of Gold. In living in the mining town for extensive ethnographic research, I also came to understand the myriad ways in which spiritual forces and the numinous, more broadly, were central to these contests, as well as to broader reckonings of histories, ancestors, justice, belonging, property, and much else.

This town and its gold had long been important politically, economically, and spiritually – long before British colonialism violently descended upon the land and the people. The gold in the town was one of the main objects of desire for colonial violence and conquest, especially in the imperial expansion north of the coast into the Ashanti Region, in which the town of Obuasi sits. In the postcolonial nation-state of Ghana, there are searing contests over gold mining, which many consider to be a poisoned chalice of the country’s heavily liberalized economy. These contests include matters concerning the rights of small-scale Ghanaian miners, the sovereign accrual of wealth, the proper understandings of value and moral economy, and the activities of transnational mining corporations, which are often socially and environmentally disruptive.

Conflicting, shifting understandings of spiritual and social ownership and belonging are also central. In light of all of this, the focus on gold – itself governed by spirits – within Ghana appeared to me to be a prime site for a study of the rich confluences of sovereignty, spirits, law, and political rebirth in contemporary worlds. Abstract theoretical narratives so often obscure many of these features. Ethnography, as I see it, can bring to light so many things left aside in more abstract theorizing and contemplating of social life.

How has your project developed or changed throughout the research and writing process?

To be honest, my research and writing brought one surprise after another, as ethnography so often does, all being well. My fieldwork experiences entirely rewrote and reconstituted my understanding of the research processes, as well as of the resulting written works, including this Fires of Gold book. What I ended up writing was nothing like what I had envisioned prior to living in Ghana for a long period of time. The central arguments of the book came as illuminations directly from the field research, even as the interventions engage wider debates in anthropology and social theory.

The book sets forth two key arguments. The first concerns the reconstitution of sovereign power and the central roles of shadow sovereigns, or sovereign-like authorities that operate alongside the legal system and police, adjudicate, or otherwise govern. In the deeply liberalized setting, the legal system at times appears to be waning or absent in domains such as corporate mining conflicts. However, the law is very much present at all times, even when seemingly invisible, as it provides crucial background ordering mechanisms through its rules and its ever-present potential force. Moreover, the liberalized economy and legal system actually help to generate key forms of shadow authority. The primary shadow sovereigns at play here are the mining company, the informal miners’ association, a casual labor union, grassroots advocacy organizations, and various religious and spiritual forces – Christian, Islamic, and other indigenous African ones, particularly Akan authorities.

Second, the book argues that religious figures and spiritual forces are crucial to anchoring and animating the powers of sovereigns and shadow sovereigns. They do so in ways that are multifaceted, multidirectional, and multivalent. The spirits, writ large, do not empower or serve one political end versus another, or one group versus another, in any sort of straightforward fashion – for example, supporting the resistance of casual laborers or dispossessed farmers versus the power of the transnational mining corporation. Instead, there is a vast, deeply textured, and highly variable field of spiritual forces that animate, co-create, and otherwise suffuse mining, politics, law, and the rest of life, including the afterlife. Fires of Gold argues that these mining contests, moral economies, and social worlds cannot be fully understood without careful attention to their spiritual dimensions and interplays.

What questions for future investigation has the project sparked?

In this book, I trace a world in which miners, activists, politicians, chiefs, lawyers, religious figures, and others have helped to generate, on the ground, new constellations of sovereign and shadow sovereign power. Sovereign power here has become at once disaggregated and, within these novel separated forms, often arranged hierarchically. This internal vertical scaffolding, in many ways, mirrors those in ancestral, customary, and state-based orders. It is an intricate interplay of power and signification, one in which the spirits prominently feature and one in which the past clearly, though partially, reincarnates in novel forms of the present. I maintain that this is the case not only in Ghana but throughout much of the contemporary world. To my mind, fascinating domains for further study would concern whether, how, and to what extents these novel forms of labor, moral economy, spirituality, and sovereign power resonate with phenomena elsewhere. How might such resonances contribute to furthering theorizing concerning shifts in law, sovereignty, power, and the sacred in the contemporary world?

Why should people read this book?

I hope that people will read the book if so inclined for many reasons, but perhaps primarily for a portrayal of a world in which people are powerfully engaged in co-creating a postcolonial rebirth of law, politics, and sovereign power. In the course of their embodied struggles, they are renegotiating the core meanings of labor and value, and they are fashioning new visions of justice and freedom from within the crucible of extractive capitalism that predominates in contemporary society.

Learn more about other publications by Princeton University faculty in the humanities by exploring our Faculty Bookshelf.