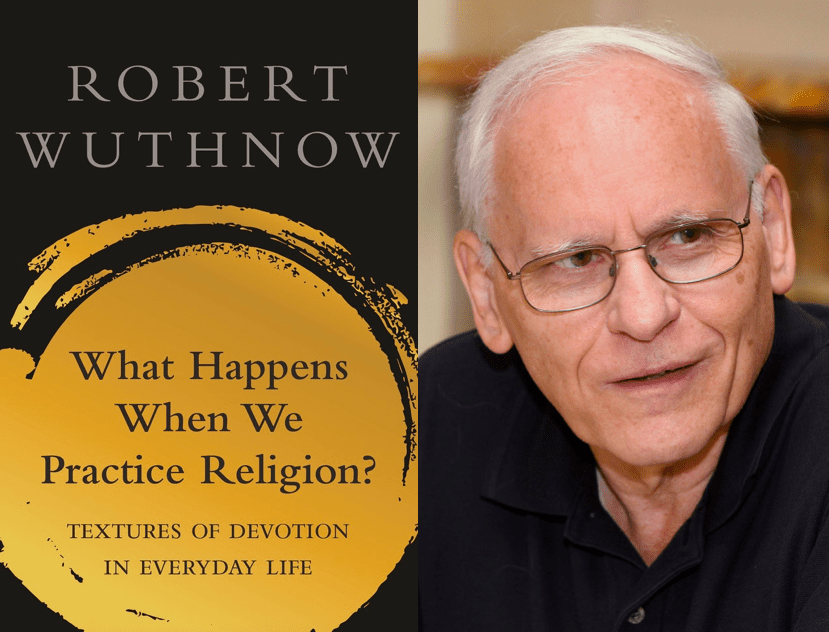

Robert Wuthnow is Gerhard R. Andlinger `52 Professor of Sociology. His book “What Happens When We Practice Religion?: Textures of Devotion in Everyday Life” was published in May 2020 by Princeton University Press. This retrospective Q&A is part of an effort to acknowledge all the wonderful books published early in the pandemic.

How did you get the idea for this project?

It grew out of the Center for the Study of Religion, which I directed for many years, including a weekly research-in-progress seminar with graduate students. Through the seminar I had the opportunity to interact with students from anthropology, comparative literature, English, history, politics, and religion, as well as from sociology – learning how they approached their work, the questions they asked, and what literatures they were reading. This interaction was as enormously enriching for me as it was for them. It inspired me to think harder about what we mean by religious practice and to search more widely for ideas about how to study it.

How has your project developed or changed throughout the research and writing process?

Well, in some of my work already in the 1990s I’d been looking at the various ways in which ordinary people talked about their religious practices and I was interested in the descriptive work that was emerging under the heading of lived religion. But as I delved more deeply into the interdisciplinary literature, I found myself reaching increasingly beyond the study of religion itself and confronting questions being raised in other fields that were insightful conceptually as well as empirically. As one example, there has been a profound shift in the theoretical literature away from classificatory schemas toward process models – a shift I try to describe and explain; similarly, there is much to be learned from the cognitive psychology literature about situational cues, habits, intentions in action, and somatic memory. These are insights that I suggest can be of value whether we are interested in mindfulness meditation, the history of prayer closets, the ethnic meanings of home altars, or why William James so often wrote about walking as a spiritual practice.

What questions for future investigation has the project sparked?

This book is centrally concerned with the micro-level practices that individuals do and experience in everyday life, which leaves out the larger practices in which groups and organizations engage when they deal with big questions about politics, human rights, economic inequality, and citizenship. My next book – Why Religion Is Good for American Democracy – is tackling some of those questions by examining the give-and-take advocacy to which religious diversity has contributed since the 1930s in debates about authoritarianism, liberty of conscience, freedom of assembly, human dignity, immigrant rights, the wealth gap, and the current pandemic.

Why should people read this book?

My hope is that readers will find insights from the hundreds of fascinating studies I discuss in this book that will be helpful in their own studies of religious and spiritual practice, or perhaps even in their own practices. This is not a book meant to chart a distinctive approach of my own. Its intent rather is as an invitation to look more closely at religious practices in whatever form they take and to build on the insights that have been developing in so many interesting ways over the past few decades. It is an invitation especially to scholars of religion but also to scholars across the humanities and social sciences.

Learn more about other recent publications by Princeton University faculty in the Humanities by exploring our Faculty Bookshelf.