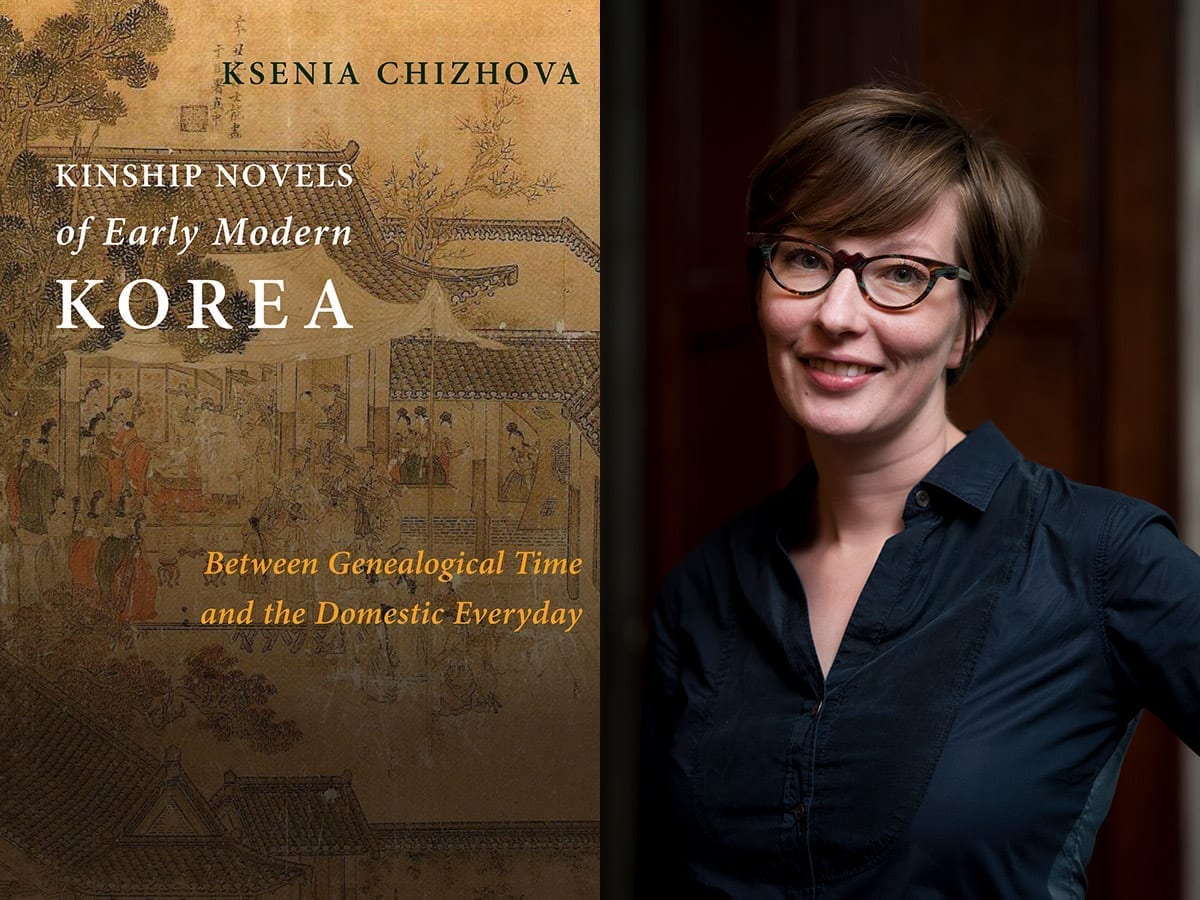

Ksenia Chizova is Assistant Professor of East Asian Studies. Her new book “Kinship Novels of Early Modern Korea” is published by Columbia University Press. She will teach “East Asian Humanities II: Traditions and Transformations” (HUM 234 / EAS 234 / COM 234) in Spring 2021.

How did you get the idea for this project?

Violence and bloody family feuds constitute the core of the so-called lineage novels (kamun sosŏl) that my book investigates. Such subject matter becomes ever more puzzling when we consider that the main audience for these texts, which circulated between the late seventeenth and early twentieth centuries, were elite women of Korea, who were subjected to exacting comportment standards and domestic discipline. In graduate school, when I first came across what is the longest novel of early modern Korea, The Pledge at the Banquet of Moon-Gazing Pavilion (Wanwŏl hoemaeng yŏn), I was immediately intrigued by the family drama unfolding around the main heroine: violent, beautiful, and clever Madame So, who sets on the journey of vengeance, murder, and intrigue against her adopted stepson. Begrudging the heirship priority this stepson receives over Madame So’s own sons, who are born later, Madame So’s person embodies the conflicts engendered by the institutions of primogeniture and heir adoption that sustained the lineage structure of early modern Korea. As I was reading this novel, I was pondering the affective aspect of women’s life within patriarchal households. Kinship Novels of Early Modern Korea traces the literary elaboration of the so-called genealogical subject—an emotional self, socialized through prescriptive structures of patrilineal kinship. Lineage novels illuminate the domestic conflicts of feelings that were produced within the patrilineal culture of Korea and were experienced particularly dramatically by elite women.

How has your project developed or changed throughout the research and writing process?

As my work continued, I became aware of the historical connections between the Korean lineage novel and the global emergence of fictional realism. Global silver flows from South American colonies and subsequent monetization of economies across the world unmoored traditional social structures, prompting fictional narratives to shift from epic to biographical, with stories of personal lives and feelings beginning to occupy narrative centerstage. Ning Ma illustrates these patterns in her visionary study The Age of Silver: Rise of the Novel East and West (Oxford, 2017). While Korea’s connection to global silver flows was indirect, and monetization of its economy remained more modest compared to that of its neighbors China and Japan, Korea was influenced by the literary developments that were themselves produced by the impact of commercialization on cultural production. The so-called cult of qing—intense interest in feelings as the locus of personal authenticity—swept through Chinese philosophy, literature, and drama. When it reached Korea, its imprint became discernible within the idiom of the lineage novel, which begins to probe into the personal dimension of kinship life just when Korean patrilineage takes shape. Notably, lineage novels privilege troubled protagonists, who first rebel but then settle into prescribed kinship roles. Structurally, lineage novels resemble the coming-of-age narratives of the Bildungsroman, although the context of these personal life trajectories is determined by the Korean kinship life. Violent stepmothers and prodigal sons from the pages of early modern Korean fiction are linked to the global flow of ideas that began to privilege private life stories and feelings across the world.

What questions for future investigation has the project sparked?

Through lineage novels’ exquisitely crafted manuscripts I encountered vernacular Korean calligraphy—a scriptural practice that originated in palace decorum and spread to elite households to become a necessary ingredient in elite women’s learning. Curiously, modern fonts in North and South Korea hark back to this 17th-century aesthetics. My unrelenting fascination with this intricate art form inspired my next book project, tentatively titled Hangeul the Great: Women in the Media History of the Korean Script. In this second book I plan to investigate the techno-aesthetic relays of vernacular Korean calligraphy in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. It will explore calligraphy’s transition from a practice centered on royal and elite women to modern exhibition, classroom, and print industry, as well as the simultaneous social shift in which women became decentered within androcentric national culture.

Why should people read this book?

Family drama is a timeless cultural genre, and this is what makes the stories of early modern Korean protagonists so fascinating to me. But the familiarity of family conflict is deceptive. Lineage novels operate within a universe with radically different conceptions of self, family, and society, and Kinship Novels of Early Modern Korea lays out the historically specific grammar of emotions produced in that time and place. If I were to emphasize another aspect of this study, I would like to note that kinship experience is described not from the vantage of genealogical chart, but from the immediacy of kinship life. The project not only probes into the feelings of kinship, but also into the embodied intimacy involved in manuscript making and preservation, as well as rise and fall of the genealogical subject in literary production. This book leads the reader into the thickness of Korean kinship life.

Learn more about other recent publications by Princeton University faculty in the Humanities by exploring our Faculty Bookshelf.