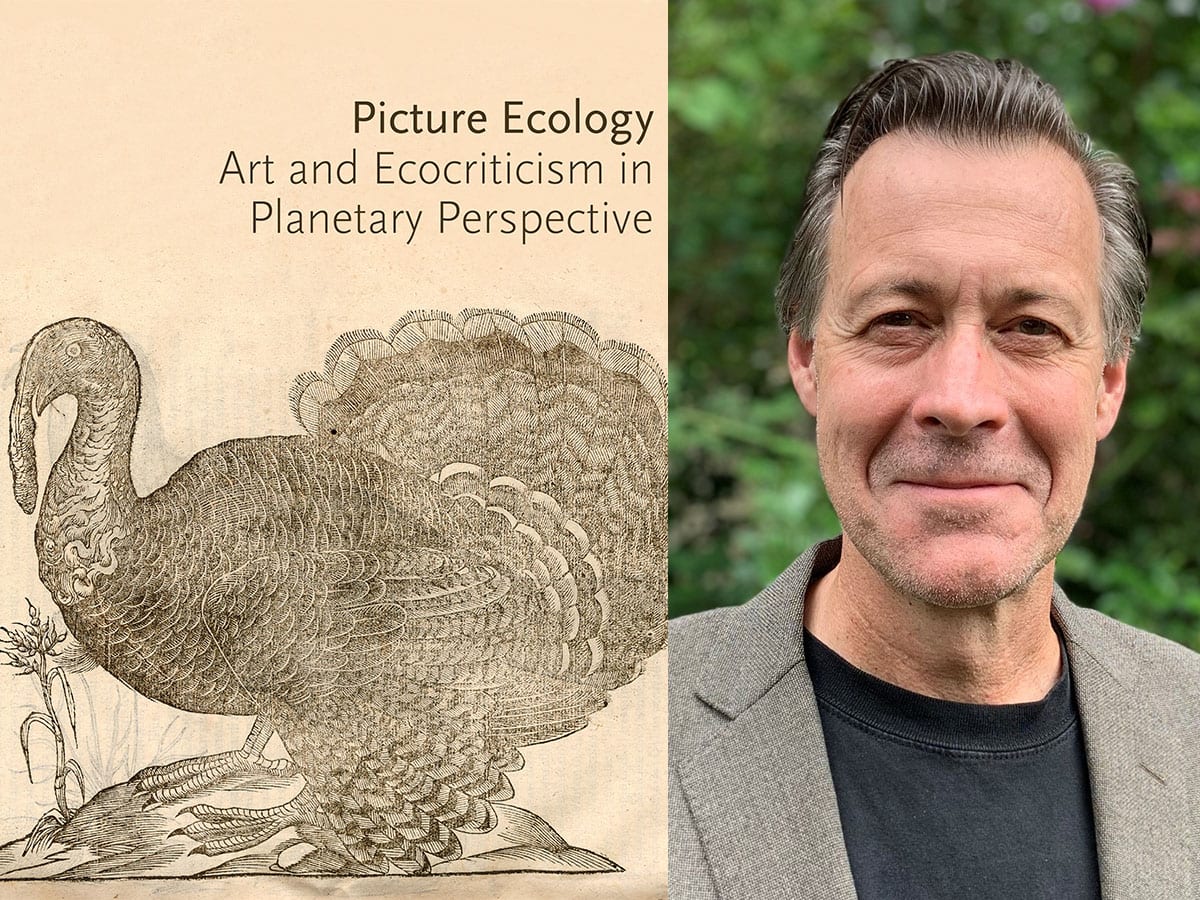

Karl Kusserow is John Wilmerding Curator of American Art at the Princeton University Art Museum. He edited and wrote the introduction for “Picture Ecology: Art and Ecocriticism in Planetary Perspective,” which is published by the Princeton University Art Museum.

How did you get the idea for this project?

The volume grew from talks first presented at a symposium convened during the Princeton University Art Museum’s 2018 exhibition Nature’s Nation: American Art and Environment, which I co-curated with Alan C. Braddock, former Belknap Fellow at the Humanities Council. The show and its catalogue offered a new, environmental way of understanding American art over three centuries. The idea for the conference and resulting book was to expand the scope of the exhibition to engage art of a variety of times and places beyond the geographical and temporal focus of Nature’s Nation. Hence its subjects range widely: from historical and contemporary Chinese landscape representation, to seventeenth-century Mughal animal painting, and, closer to home, to twenty-first-century photography of California wildfires and a drowning Louisiana.

How has your project developed or changed throughout the research and writing process?

As a collective enterprise, it changed a lot, in keeping with the individual evolutions of its sixteen contributors’ essays, many of which were substantially reworked and some largely recast. What remained constant is the commitment to ecocritical interpretation, which seeks to broaden the traditionally anthropocentric orientation of the humanities to address what has traditionally been relegated to the background: the existence, standing, and agency of the great diversity of life on earth. This critical lens extends moral and ethical consideration and value to it all. Ecocriticism looks at environmental attitudes and history to understand how humans have differently construed the relationships of our species to the rest of creation, and the effects that these relationships have had. A key part of much ecocritical work today, and a priority we hold in the book, is environmental justice. This approach focuses on the politics and ethical dimensions of both inter-species and intra-species (or human) relations, recognizing that those with different access to power experience “the environment” differently.

What questions for future investigation has the project sparked?

My contribution is called “For the Birds: Pope Francis, Saint Francis, and Ecocritical Iconology,” which was a stretch for me as an Americanist because it took me to a European context. Nevertheless, I wanted to explore the topic because I had read Pope Francis’s encyclical on the environment and found it quite affecting. The experience of moving beyond my comfort zone, in terms of both time and place, in my own essay and in editing others, gave rise to an idea for a larger exhibition project. Tentatively titled (somewhat hokily, if that’s a word) “HumAnimal”, this exhibition will look at the human-animal nexus represented trans-historically in visual culture throughout the Western hemisphere, embracing Pre-Columbian, Latin American, and Native American traditions, as well Euro-American culture. The thought is to apply the central insight of ecofeminism—that, in terms of domination and exploitation, men are to women as people are to the planet—to an exploration of how different cultures have pictured animals and human-animal relations.

Why should people read this book?

With the current planetary crisis, we have to acknowledge that business as usual isn’t productive or even possible anymore, and that our climate situation constitutes the greatest urgency among all emergencies. Despite the impacts of the atomic bomb, people haven’t until now fundamentally grasped that we as a species have the power to destroy the world, and are in the process of doing so. That realization makes what we do as cultural critics different. It changes our relationship to what we study. Ecocriticism seeks a means to address this new paradigm with the traditional tools of the humanities: history, morals, ethics, persuasion, and the imagination. Picture Ecology’s essays do just that.

Learn more about other recent publications by Princeton University faculty in the Humanities by exploring our Faculty Bookshelf.