By Ruby Shao ’17, Humanities Council

The Prosthetic Tongue: Printing Technology and the Rise of the French Language, the first monograph of Katie Chenoweth, Associate Professor of French in the Department of French and Italian, recently won the Aldo and Jeanne Scaglione Prize for French and Francophone Studies from the Modern Language Association of America. Published through the University of Pennsylvania Press in 2019, the book argues that the printing press introduced French as the world has since known it.

“How the texts were being produced had a major effect on the texts themselves,” Chenoweth said. “The whole language itself gets affected, imprinted, by this new technology.”

Chenoweth teaches in the Humanities Council’s course “Interdisciplinary Approaches to Western Culture.” In addition, the Council awarded her a 2020–2021 Magic Grant for “The Seminars of Jacques Derrida: An Online Archive.”

Scholars have long attributed French’s popularization to printing. But they have generally construed the invention as a capitalist tool to spread an already standardized medium. By contrast, The Prosthetic Tongue claims that the innovation shaped the language.

“What we call a native language is born in the print shop,” Chenoweth explained. “This thing that seems the most natural, the farthest away from technology, is actually produced by technology. The history of the French language, which we tend not at all to think about in relation to media, is totally determined by media.”

Attaining mechanical reproducibility, the natural mother tongue, once purely oral, attached to the artificial printing apparatus, thus occupying not only the mouth but also books as an unprecedented category of language, Chenoweth noted. She compared French to a prosthetic, lifelike instead of living.

The project began as Chenoweth’s dissertation, which she defended at Brown University in 2009. She noticed that twentieth-century French thinker Jacques Derrida’s expression of alienation from even his own mother tongue in Le monolinguisme de l’autre, meaning The Monolingualism of the Other, applied to the sixteenth-century literature she was perusing. To explain the malaise, she sought to document the sudden evolution of French out of Latin.

Though the dissertation lacked any mention of media, in later work, Chenoweth began seeing that questions about the role of technology in our lives today echoed sixteenth-century discussions of printing.

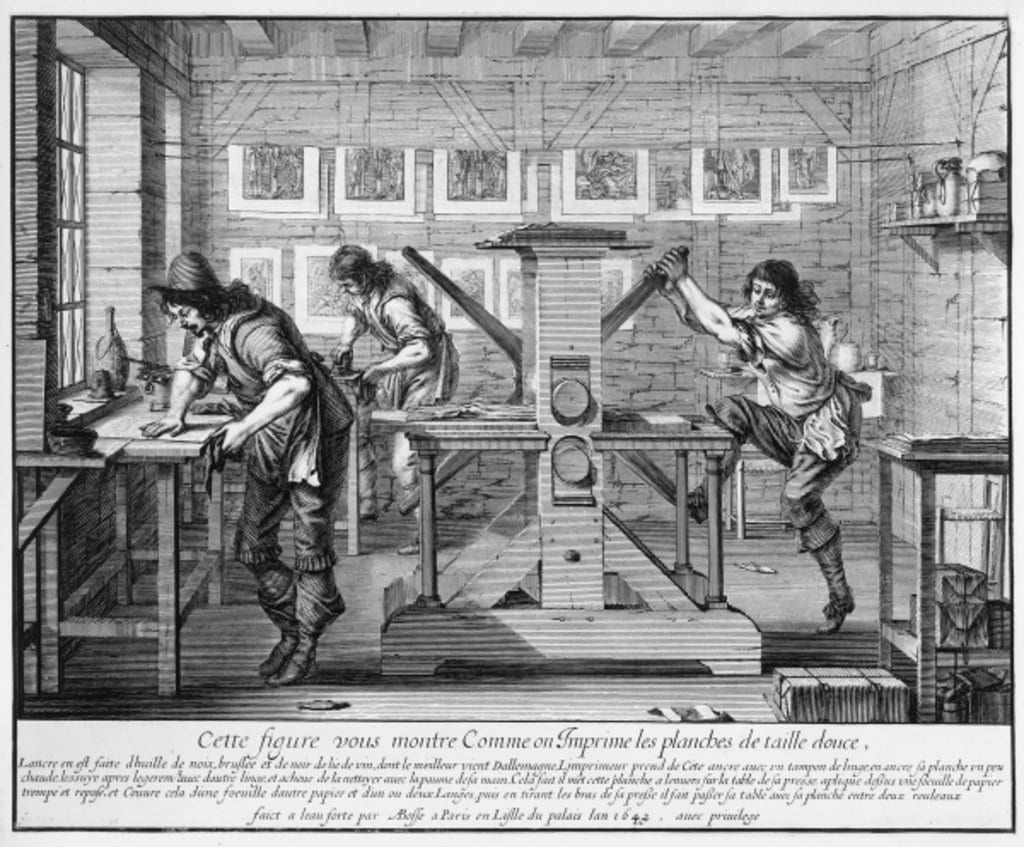

For example, new media like Twitter or Facebook force people to notice the channels through which they connect to one another, with everyday communication infiltrated by novelties like the hashtag and @ symbol. Likewise, Renaissance printers invented accents to transform text into a kind of guide for the voice, teaching readers to pronounce the language. In one radical case, Geoffroy Tory added the cedilla, which resembles a hook, to the c in many words like français to signal a soft pronunciation, a practice that still persists.

As Chenoweth documents, though, some linguistic experiments failed. Certain printers tried to make French writing phonetic, so that it could be spoken even if it became dead like Latin and Greek. They fiddled with spellings, such as k’s in the place of c’s.

Self-aware and interventionist, printers like Tory recognized their work as revolutionary, even necessary for the survival of the language. However, France also simmered with resistance to the revolution. Fifteenth-century monk Johannes Trithemius penned In Praise of Scribes, which argued that printing would destroy knowledge, devalue books, and otherwise extinguish the traditions, institutions, and cultural transmission of the period.

In writing The Prosthetic Tongue, Chenoweth drew on her interdisciplinary training from Wesleyan University, where her major in the College of Letters synthesized literature, history, and philosophy from antiquity to modernity. From these three disciplines, she analyzed rhetoric using close reading skills, examined the material dimension of textual production, and explored the changes made possible by the printing press.

“This is really a book that is trying to think about language from the standpoint of philosophy, history, literature, and even a little bit of linguistics, together, to get that big picture of what’s happening to language,” she said.

Chenoweth noted that The Prosthetic Tongue can teach readers to grow more sensitive to media, including their relationships with it. Armed with her historical perspective, they can attune themselves to the enduring power of technology as both a danger and a source of creative potential.