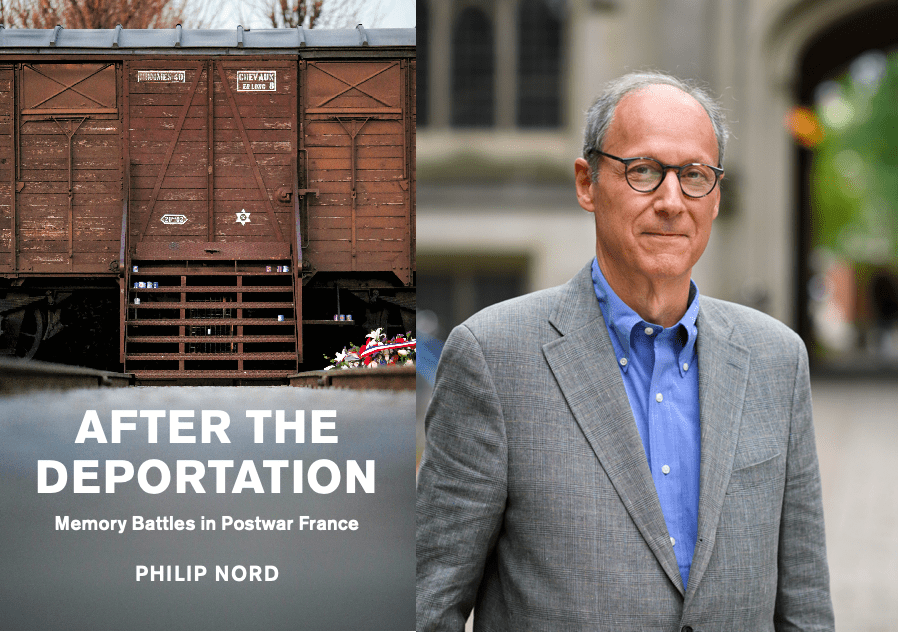

Philip Nord is Rosengarten Professor of Modern and Contemporary History. His latest book “After the Deportation: Memory Battles in Postwar France” is published by Cambridge University Press.

How did you get the idea for this project?

I finished an article dealing with an arts organization sponsored by the Vichy regime. A number of the participants were young Catholics, destined to play a role in postwar French life, among them Paul Flamand, the editor at Le Seuil publishing house. In the decades after the Liberation, Le Seuil published a series of books touching on Holocaust-related themes, André Schwarz-Bart’s The Last of the Just (1958) and Saul Friedländer’s When Memory Comes (1972) being prime examples. I recalled that the Catholic novelist and Nobel laureate François Mauriac had written the preface to Elie Wiesel’s Night when it was first published in 1959. It dawned on me that some Catholics had taken an interest in the Holocaust, and I wondered what the nature of that interest was. This is how I got started on my project. The subject of Catholic-Jewish dialogue takes up two chapters of the book.

How has your project developed or changed throughout the research and writing process?

Once I got started, the project expanded rapidly. I realized that I wanted to talk not just about the deportation of Jews but also about the deportation of résistants, and how the two experiences were memorialized. It didn’t take long to discover several things. First, that Deportation memory, right from the Liberation, was a bone of contention, hence my choice of title—memory battles—a phrase borrowed from French colleagues. Communists and Gaullists were among the principal combatants, but others soon entered the lists: non-communist leftists, Cold Warriors, Catholics, and Jews. The presence of Jews in the debate was, for me, something of a surprise. I shared in the general assumption, still prevalent among publics both here and in France, that Jews had been silent on the matter of the Holocaust in the war’s immediate aftermath, not finding a voice until much later. The various currents or familles d’esprit that I identified were not content to remember the dead but had stories to tell about them that gave meaning to tragedy and that instructed those who had survived it what values to live by in the present. These narratives, moreover, took more than one form. They might be etched in stone and bronze, and in fact, when I settled down to archival research, it was with deportee monuments that I began. But they might also take the form of films, memoirs, novels, paintings, and so on. What struck me right away was how large the corpus was and how imaginative. It’s not a revelation to say that the postwar decades were a moment of exceptional creativity in French culture, but less obvious is the role that Deportation-themed material played in this burst of invention.

What questions for future investigation has the project sparked?

My story peters out in the mid-1990s and a lot has happened since then. The outpouring of Holocaust-related material in France in the last three decades has been enormous. There’s work to be done here. Additionally, I focused on high places of memory: that is, major monuments and works that had national, even international resonance. But there are local and neighborhood memorials of all kinds that have proliferated in recent times. Local memory, grassroots memory, may tell the same kind of stories that I analyzed, but it may also have other objectives. That remains to be found out.

Why should people read this book?

Readers might read for the argument. How was it that Holocaust memory, always a presence, emerged from the pack of competing memories and came, in the concluding decades of the last century, to occupy center stage? What was French about this story? It’s also my hope that those who take an interest in France’s postwar cultural scene will encounter familiar terrain made unfamiliar because of the angle of approach adopted. I don’t look at the scene head on but through the lens of memory battles about the war, the concentration camp experience, and what the French prefer to call the Shoah. If nothing else, as I write in the conclusion, I hope that readers “will feel drawn to revisit or visit for the first time the art, books, monuments, and movies that have been encountered in the preceding pages.”

Learn more about other recent publications by Princeton University faculty in the Humanities by exploring our Faculty Bookshelf.