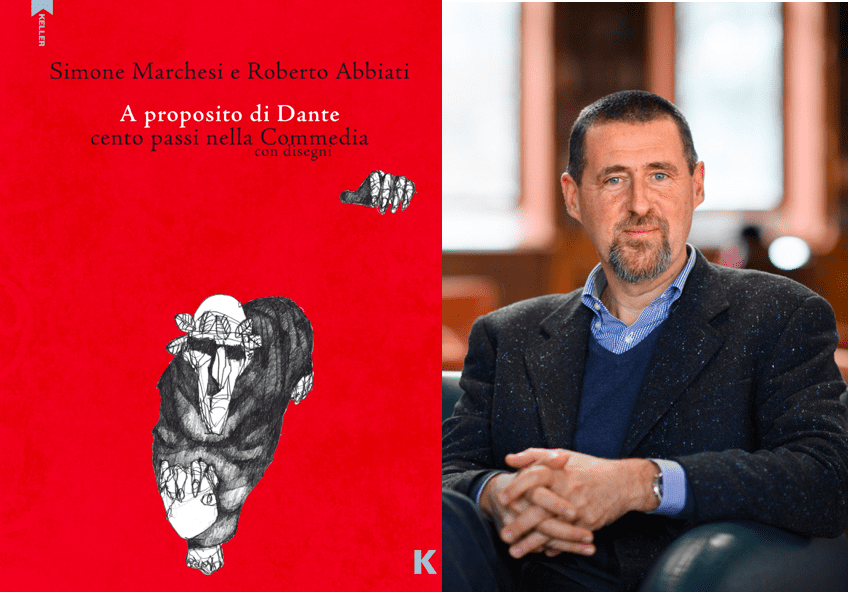

Simone Marchesi is Associate Professor of French and Italian. His new book “A Proposito di Dante” is illustrated by Roberto Abbiati and published by Keller Editore.

How did you get the idea for this project?

This project was, in a way, dictated by circumstances. The first of which is that 2021 will be an anniversary year for Dante Alighieri, the author of the Divine Comedy, a text I have regularly taught at Princeton for the past twenty years. Reflecting on how the anniversary of an ancient poet’s death may also provide a testament to the longevity of his influence, I realized that Dante’s legacy is vital no less for our literary culture than for our visual imagination. Whence came the second determining circumstance for the project: producing a book that would integrate words and images called for the collaboration of a visual artist. Thanks to colleagues and mutual friends in Italy, I was introduced to Roberto Abbiati, whose powerful illustrations of Herman Melville’s Moby Dick had left a deep impression on me. He agreed to come on board with the Dante project, and the three years that we have spent commenting Dante’s Comedy together through words and images, have proved a truly exhilarating and formative experience.

How has your project developed or changed throughout the research and writing process?

I initially approached the task of illustrating Dante as I had been trained to, namely by accumulating historical, philosophical, and literary material around the text. But this method did not take me very far with Roberto. He is an incredibly keen and engaged reader of the poem, who acted throughout the process as the most demanding of students. He simply would not take my word for it every time I went into lecture mode. Rather, he rightly insisted on being enabled to see the point I was making for himself. Roberto’s probing questions and lively questioning of my initially all-too-scholarly responses to Dante’s text have shaped my glosses into something quite new: a critical commentary that prompts rather than delays a reader’s direct engagement with Dante’s text. On the other hand, I like to imagine that some of the words I have said and written to him during our collaboration have contributed in a similar manner to shaping his illustrations. After all, the final product of our work has been not an illustrated edition of the poem, one that replaces the readers’ work of imagining what the poetry suggests with pre-determined representations. Rather, we have striven to provide readers with visual meditations on the text that challenge both novice and veteran ‘users’ of the Comedy to pick it up and, once again, make it make sense.

What questions for future investigation has the project sparked?

The project has essentially confirmed one initial working hypothesis, namely that Dante is indeed alive on account of the iconic imagery evoked by his work. It also opened a fully new line of research, one that investigates a different side of the visual culture surrounding the Comedy. Dante was a visionary poet whose text elicited a powerful set of visual responses, which in themselves form a visual tradition: from medieval illuminators to Sandro Botticelli, from William Blake to Gustave Doré, from Salvador Dalì to Robert Rauschenberg, to name only some of the artists who have set their hands to depicting Dante’s world. Traditional illustrations that have lent the Comedy an iconic quality only provide one side of the visual commentary to the poem: its reception. But what about its inception? Thanks to the incredible amount of iconographic data produced and made available by Princeton’s Index of Medieval Art, today we are also able to illuminate the visual elements at the root of the poem’s imaginary complex. In collaboration with IMA Director Pamela Patton, I have launched a digital project to integrate the Princeton Dante Project with the IMA. The connection between these two online archives of texts and images is designed to provide today’s students of Dante with glimpses of what medieval readers would ‘see’ when Dante’s text mentions, evokes, or describes an object of this world or of his imagined afterlife. The work is in progress, but we hope that this philological approach will soon help students and scholars interested in the Comedy to reconstruct the visual horizon of expectation Dante shared with his contemporary readers.

Why should people read this book?

Mainly for two reasons. First, because the words we offer interrogate moments in the Comedy that have overly naturalized themselves in our reception of the poem and that we therefore seek to destabilize. In challenging perceptions of the poem as a static literary monument, we open opportunities for readers to ask their own questions to the text, confident that the Comedy will answer them in new ways. Readers may also want to pick up our book because Abbiati’s images join the long and distinguished tradition of Dante illustrators in the same challenging spirit. In their richness and often surprising approach, they embody and model a contemporary engagement with the text. They show that, in the end, it is only by continuous re-imagining in the hands of readers that works of literature truly live.

Learn more about other recent publications by Princeton University faculty in the Humanities by exploring our Faculty Bookshelf.