By Ruby Shao ’17

Nearly seven centuries after his death, Dante continues to attract global acclaim for composing The Divine Comedy, an Italian epic poem about a man’s journey from hell through purgatory to heaven. Yet analyses of the story’s visual components have considered the artwork it inspired, while neglecting what its readers would have envisioned, according to Simone Marchesi (French and Italian).

Overturning the status quo, he and Pamela Patton (Art and Archaeology) are leading “Literary Visualizations,” which is hiring two graduate student research assistants with a Rapid Response Magic Grant of the Princeton University Humanities Council. Patton and Marchesi believe that “Literary Visualizations” will serve as the first tool evoking the mental landscape of Dante.

“This project should challenge the merit of traditional visual commentaries to the poem, both by offering a philological reconstruction of what kind of visual response the poem might have invited readers to deploy and by inviting a theoretical reflection on what it means to ‘imagine’ Dante’s text today,” Marchesi said.

For example, scholars have inspected depictions, from late medieval manuscripts down to twentieth-century drawings, of an adulterous kiss between Paolo and Francesca. But Marchesi wants to show how such scenes would have looked to Dante’s initial audiences. He argues that Paolo and Francesca seduced each other not in the room of a bourgeois house, as portraits have implied, but rather in a garden reminiscent of Eden. For Marchesi, the indoors interpretation has obscured crucial allusions to the prelapsarian innocence of Adam and Eve, the affair between Guinevere and Lancelot, and the conversion of St. Augustine as relayed in his Confessions.

“If modern reactions to the work of imagining a scene in The Divine Comedy have gone so astray, this is because modern readers simply stopped listening to the text. They—and by ‘they’ I mean ‘we’—stopped mining its language for clues about the way one is supposed to imagine its content,” Marchesi said.

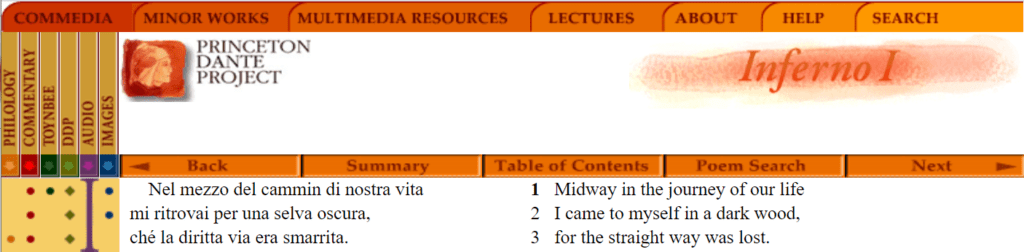

The initiative constitutes the debut collaboration between the Princeton Dante Project, operated by Marchesi, and the Index of Medieval Art, directed by Patton. Ultimately, “Literary Visualizations” will enable PDP users to scroll to a line of The Divine Comedy, click on a nearby colored dot, and instantly access filtered visual results in the Index. The tool will not merely report the appearances of objects, but instead reveal ways that people in the Middle Ages represented those objects, such as by construing leopards as spotless.

Marchesi conceived of “Literary Visualizations” in trying to enhance the PDP. Founded over two decades ago, the PDP facilitates teaching at Princeton. The website supplies resources that transport readers back into the cultural context of The Divine Comedy.

“The Project gives a huge amount of freedom to researchers to pick what they want to work on, and to develop scholarly, solid arguments independently,” Marchesi said. “You don’t need to be held by the teacher’s hand, led through the intricacies of the tradition. You do have the tradition there at your fingertips.”

Copyright restrictions have reduced the PDP’s store of pictures over the years. Only illustrations at the beginning of each canto remain. As Marchesi sought replacement images and discussed the contemporary meaning of illustrations with an Italian publisher, questions emerged about the visual apparatus constructed by The Divine Comedy.

Meanwhile, his brainstorming benefited from developments surrounding the Index, which has long focused on research. When Patton started heading the Index in 2015, she expanded it to support pedagogy. Moreover, she and her staff rebuilt its outdated database to make it easily searchable, including by faculty, from 2017 onward.

Two years later, Marchesi embraced the new opportunity by taking his freshman seminar “Dante’s Inferno” to the Index, where they learned about items that Dante and his readers would have seen. Some of the students’ final papers incorporated visual aspects, alerting Marchesi to the fundamental importance of such work. Integration of the Index’s materials with the PDP struck him as necessary.

Further momentum for “Literary Visualizations” came from a shift in the field of comparative literature, where scholars are now investigating pictures, according to Patton. “We’re sitting on a trove of images at just the moment when people are becoming very interested in it,” she noted.

At the outset of the initiative, Marchesi expected machines to match words in The Divine Comedy to graphics in the Index. However, he soon discovered that the task requires people. They must not only identify which images the text is mobilizing, but also determine the best matches.

“AI cannot do what a person with a PhD, or an MA at least, in art history or in Dante studies in Italian, is able to do, because the discriminating decision-making is not there. And so over and over, we’ve proven this to ourselves: we need humans, and we need educated humans, not just anybody,” Patton explained.

Marchesi outlined the process using the opening lines of The Divine Comedy: “Midway in the journey of our life, I came to myself in a dark wood, for the straight way was lost.” He, Patton, and their graduate student research assistants might ask themselves, “Which object is dominating here?” They could choose “wood,” then scour the Index for medieval forests familiar to an early 14th-century reader. They would then follow comparable steps for another phrase, like “the straight way.”

“You identify a point in the text that could provide an image because there is an object there, and you see what the logical visual imagination of the poem was suggesting,” Marchesi summarized.

This stage will take the greatest amount of time. Subsequently, the Center for Digital Humanities will handle the technical side, which Patton deemed straightforward, such as involving the insertion of hyperlinks. According to Marchesi, he and Patton dream of presenting on “Literary Visualizations” the weekend of November 13, 2021. They would do so as part of a Princeton conference celebrating Dante’s ongoing vitality in popular culture upon the 700th anniversary of his death.

Marchesi credited Princeton’s supportive interface between tradition and innovation with making “Literary Visualizations” possible. The team anticipated that the initiative will reshape teaching and research, while enlightening art historians as to how images function in other disciplines.

In keeping with the PDP’s mission of opening Dante studies at Princeton to people around the world through the Internet, anyone will have the chance to benefit from “Literary Visualizations,” Marchesi said.

“Teachers try to build bridges between the reader and the text, and then remove themselves from the equation,” he said. “Every encounter with a text is ultimately a personal encounter.”