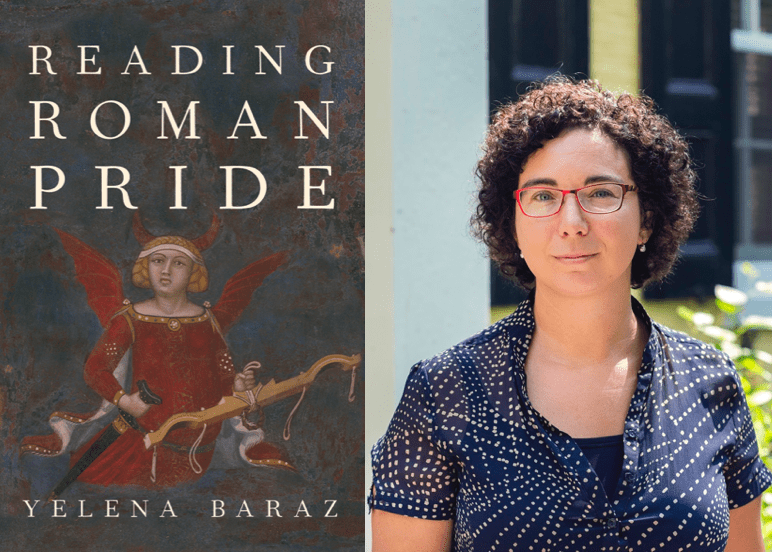

Yelena Baraz is the Kennedy Foundation Professor of Latin Language and Literature, Professor of Classics, and Behrman Professor in the Humanities Council. Her latest book “Reading Roman Pride” is published by Oxford University Press.

How did you get the idea for this project?

I was vaguely unsettled by a very famous line in a very famous poem by Horace, the conclusion of his three-book collection of odes. He addresses his Muse and tells her to feel pride in his poetic achievement. It seemed to me that the meaning of these prominent lines was not as obvious as we assumed, that the emotion he was evoking might not be straightforwardly positive. It was in the back of my mind for a long time when I saw a call for papers for a conference on anti-values, and used that as an opportunity to investigate pride as an anti-value in Rome. It turned out to be more exciting and surprising than I had anticipated, and I continued exploring it until it became clear that it had to be a book.

How has your project developed or changed throughout the research and writing process?

The project evolved both in terms of objects of study and method. I didn’t know when I started where the research would lead me: I followed the surviving texts that treat pride in interesting ways, and many focal points emerged from that material. For instance, I wanted to explore how pride worked when it was assigned to non-human entities, such as places and institutions. It emerged from my reading that the city of Capua was seen as an archetype of a proud place, and this association remained remarkably stable from its defection from Rome during the Second Punic War to the Late Empire. In the book, I dedicated a chapter to investigating what it means for a place to be proud by following representations of Capua in texts of different periods and genres.

At the same time as I followed the evidence in choosing what texts and questions to focus on, I turned to a variety of approaches to produce a multi-faceted sense of pride as a concept and an emotion. Lexicography helped me understand relationships between terms that provide a window on how Romans distinguish between different types of pride; history of emotions located pride in a broader emotional landscape with specific emotional triggers, behaviors, and outcomes; a chronological reading of the material pinpointed the moment of change. It was also in the course of research that I realized how very rare references to pride as a positive quality were, and that they only began in the Augustan period. That is, they were part of the changing discourse that accompanied radical political change following the end of the Republic.

Why should people read this book?

I can imagine many points of entry into this project. It’s about how our ability to articulate emotions and values is culturally conditioned, and it showed the extent to which this particular emotion, pride, is also tied closely to changes in politics and governance. This phenomenon is something we are experiencing now in our own society. The Romans are also unique, it seems, in light of contemporary psychological research on pride. Their predominantly negative articulation is an interesting case study within history of emotions. My findings will also be important for those who are interested in Roman literature: pride is central to many influential texts, especially Augustan ones, and we’ve been reading it backwards by assuming that the positive meanings that occur later are always available. I offer new readings of pride in Vergil’s Aeneid, and in poems by Horace and Propertius. The book works closely with the language of the texts, but it can be read in many ways, and the different approaches I use speak to a variety of potential reader interests.

Learn more about other recent publications by Princeton University faculty in the Humanities by exploring our Faculty Bookshelf.