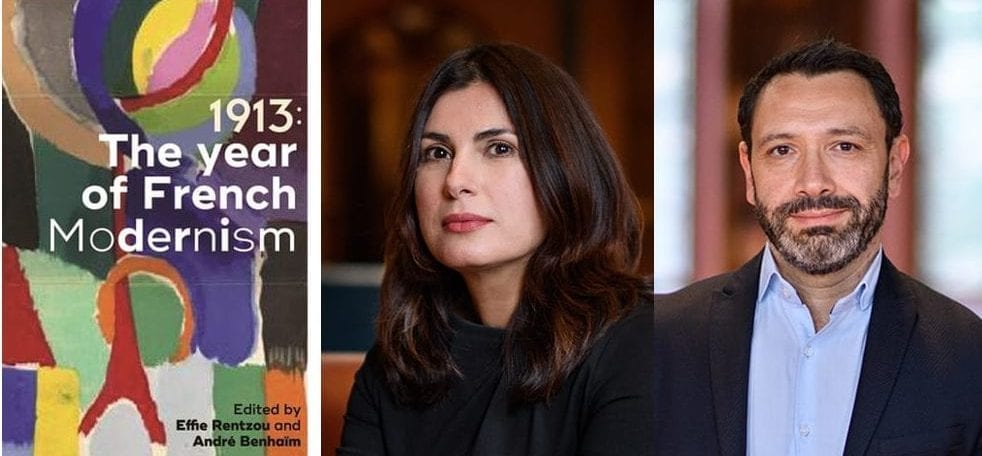

Effie Rentzou and André Benhaïm are Professors in the Department of French and Italian. Their latest book is “1913: The Year of French Modernism,” published by Manchester University Press.

How did you get the idea for this project?

The idea for this project came out from a date, 1913. Many important cultural events happened in France that year: the first volume of Marcel Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past was published, as well as Guillaume Apollinaire’s seminal poetry collection Alcools, The Rite of Spring was performed, Marcel Duchamp created his first ready-made, Eugène Atget put together the photographic album Les Zoniers, to name a few. How did all these ground-breaking books, works of art, and performances connect with each other and what story do they have to tell us about the historic moment but also about the physiognomy of modernism in France? That was our motivating question.

How has your project developed or changed throughout the research and writing process?

While initially we were more focused on individual works and their place in literary and art history, very quickly we were brought to consider the larger framework of modernism in France and worldwide. The final structure and direction of the book 1913: The Year of French Modernism were thus largely determined by our overview of modernism as a cultural phenomenon, its outlook in France, and also the place of French modernism in existing scholarship.

What questions for future investigation has the project sparked?

Modernist Studies have turned increasingly toward neglected, peripheral, national traditions in order to illuminate modernism as a global phenomenon. This book offers a view of one of modernism’s supposedly central occurrences, the French. While references to French Modernist authors or works abound in scholarship and are fundamental for the aesthetics of modernism in general–Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Mallarmé, or Proust–French modernism as a canonical category is absent. The ubiquity of these paramount figures and their canonization as key authors of modernism, as well as the centrality of Paris as a real, imaginary, and symbolic metropolis of modernity, have obscured the fact that the story of French modernism has not yet been told. 1913, The Year of French Modernism tells this story. It shows that even ostensibly central occurrences of modernism remain to be explored, it demonstrates how the global is embedded in the regional, and finally it reconstructs and rethinks the “centrality” of France for modernism as well as the meaning of “centrality.” In bringing together an array of excellent essays, we try to redraw the connections and the dialogues that created the distinctive dynamic of French modernism and, in so doing, create a collective narrative for French modernism, a domain in scholarship that remains, paradoxically, still unexplored as a canonical and coherent category. We think that this book opens the way for a more cohesive understanding of modernism in France, and thus ultimately of modernism as a global phenomenon.

Why should people read this book?

Each essay of the book discusses in depth specific works that congealed around 1913 and addresses broader theoretical questions pertaining to modernism, its aesthetics, politics, history, geography, limits, and limitations. The aim of the volume is not to be exhaustive: this is not a history of French modernism; it is not a complete snapshot of the effervescent creativity that occurred in 1913 either. Rather, through a wide range of genres and media – prose, poetry, visual arts, cinema – the essays detail and flesh out a modernist landscape. People who are interested in modernism in general, in the interconnections between the arts, or in the specific works discussed, would find the book fascinating.

Learn more about other recent publications by Princeton University faculty in the Humanities by exploring our Faculty Bookshelf.