By Jon Garaffa ’20

The switch to virtual learning won’t stop a cohort of dedicated students of palaeography—the study and interpretation of ancient writing systems along with historical manuscripts—from honing their craft.

This winter, Princeton University will join the University of Notre Dame and Stanford University to co-host the Global Digital Palaeography Workshop. Made possible through a Rapid Response Magic Grant from the Princeton University Humanities Council, the workshop aims to provide graduate students from any university in the world with an intensive introduction to Greek palaeography.

Taking place virtually from January 18–22, 2021, the course is welcoming applications through October 15. Prospective participants must demonstrate an intermediate level of classical/medieval Greek. Emmanuel C. Bourbouhakis (Classics and Hellenic Studies) and David Jenkins (Librarian for Classics, Hellenic Studies and Linguistics) will lead the course.

The instructors hope that the tuition-free and travel-free sessions will allow enthusiasts from any background to receive the education that they need, especially if they cannot otherwise obtain it. “Students who don’t attend wealthy universities could have access to a workshop on a subject like this, no matter where they are,” Bourbouhakis emphasized. “Why don’t we use this moment to distribute the knowledge a little more equitably—to those who want it and need it, rather than simply to those who can afford it?” Palaeography offers rare benefits accessed by few, as so many schools invest their resources in other areas.

According to Bourbouhakis, palaeography is useful because it expands the range of ancient and medieval Latin and Greek texts that scholars can understand. Professional palaeographers transcribe manuscripts to make them available for others to use in their research. Sometimes, hundreds of years can pass between a manuscript’s discovery and its transcription, and many manuscripts have yet to be transcribed. Hence, palaeographers offer a uniquely valuable ability to interpret antiquated writing styles and customs. With palaeography comes a greater understanding of human history.

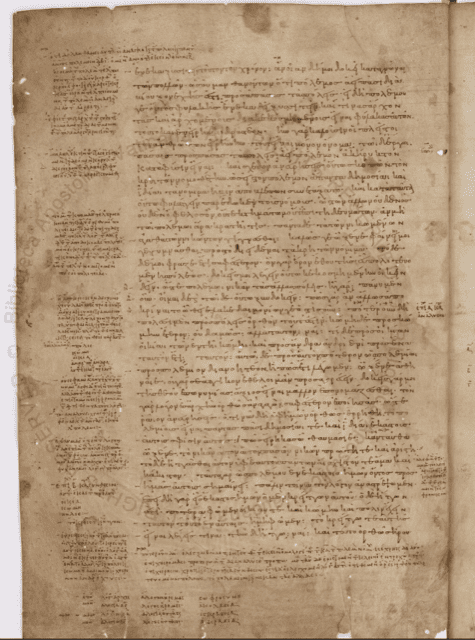

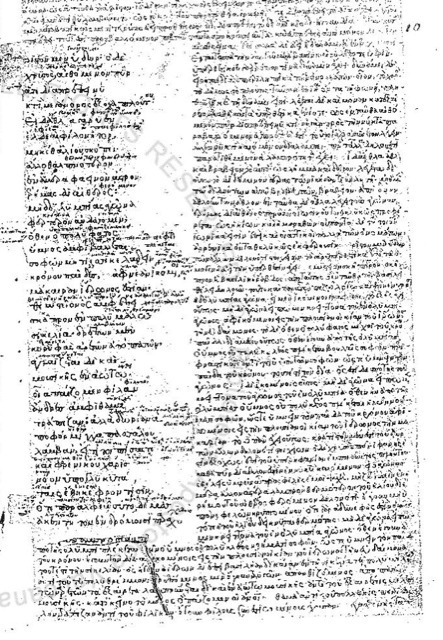

The Apostolic Library of the Vatican has aimed to capture this human history over many centuries, and the workshop will offer students a chance to explore this grand collection, Bourbouhakis added. Within the library, one can find great classical and Christian works, including the Vatican Codex, the oldest extant copy of the Bible, and the best-preserved copy of Euclid’s Geometry, which contains the first account of the Pythagorean Theorem. With a focus on the Greek manuscripts, the course will impart the skills required to conduct palaeographical research on medieval texts. Students will learn to close-read primary sources, provide accurate transcriptions, and compare differences between multiple versions of a given manuscript.

Bourbouhakis and Jenkins found inspiration for the workshop as they realized the vast potential for scholarship through increasingly digitized manuscript libraries. Originally, they intended to host the program on-site at the Vatican. Due to the ongoing COVID-19 circumstances, a virtual course proved more fitting.

However, the instructors do not see the digital dimension as a compromise. Rather, they hope that it will trailblaze virtual instruction in the field of palaeography. “We really see this workshop as something that we would do anyway!” Bourbouhakis explained. “It’s just that the circumstances have especially reminded us that this digital format was out there waiting to be explored.”

For budding students in palaeography and its related fields of ancient literature and language, Bourbouhakis recommends learning as much Greek or Latin as possible. Enjoying the language is crucial for students to endure the sheer number of hours needed to advance.

Great patience is required to master the language as well. In Greek palaeography, much of the technical challenge palaeography emerges from the language’s evolution. Eventually including both uppercase and lowercase characters, the system also changed the pronunciations of characters. Given such historical variations, palaeographers must understand the time period of each manuscript, using this knowledge to transcribe the language accordingly.

Furthermore, ligatures (glyphs in which two or more characters are joined), as well as the unique handwriting style of each author, exacerbate the difficulty of comprehension. Video tutorials on relevant topics, such as Greek scribal practices, deciphering ligatures, and abbreviations common in Greek, will serve participants as references outside of class time. Ideally, a breakthrough graduate dissertation could harness palaeographical skills to decode an unknown text for the very first time, and even to help date the text back to the period in which it was composed. All in all, palaeographical techniques greatly add to the exploratory toolbox of Latin and Greek scholars.

Looking towards the future, Bourbouhakis is optimistic that this workshop model will prove successful. “Once enough of these workshops are done—not in order to replace the earlier in-person model, but to supplement it—we may actually draw in more interested students and colleagues from out there in the world,” he declared. “This is one area of digital humanities that has a virtually guaranteed future—no pun intended.”