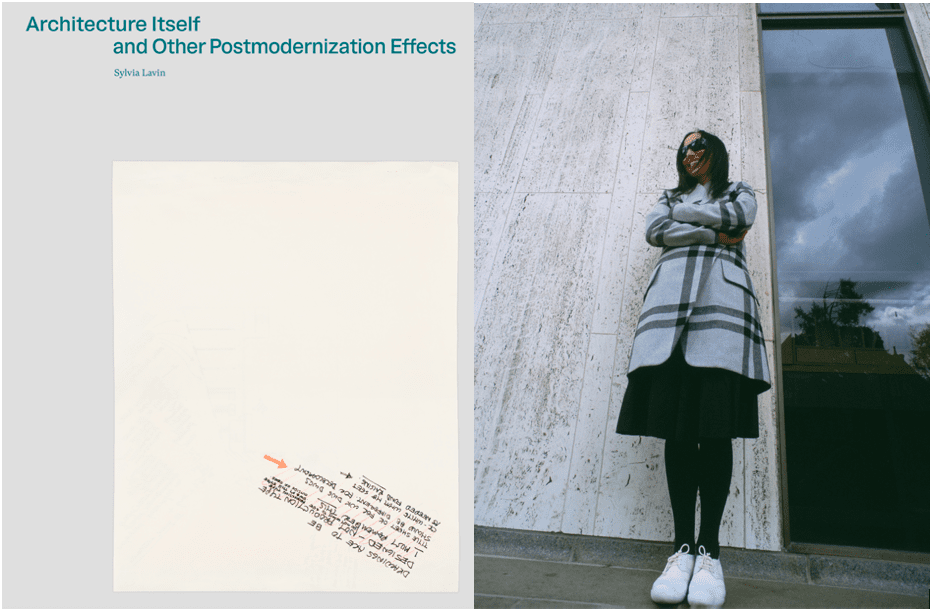

Sylvia Lavin is Professor in the School of Architecture. Her latest book is Architecture Itself and Other Postmodernization Effects, published by Spector Books.

How did you get the idea for this project?

The project was taking shape as I was contemplating moving from Los Angeles to Princeton. Los Angeles is a city long associated with modernism in its various permutations, while Princeton’s campus is deeply connected to figures who not only played a significant role in establishing the idea that postmodernism was a thing but who also introduced architecture as central to debates about its definition. This history permeates the campus in myriad ways. In 1951 Jean Labatut placed Antioch mosaics in the Architecture Laboratory (now in the Art Museum) and, as Dean, shifted the attention of students from efficiency in planning and construction to issues of meaning and experience. In 1974 the presence of a humanistic PhD program nestled in the professional school of architecture helped to produce a postmodern historiography of architecture. During the interim and well beyond, many of the architects most strongly associated with American postmodern architectural design and theory–Robert Venturi, Charles Moore, and Michael Graves, to name just a few–either went to school here, built here, taught here, or in some cases did all three.

Although this history permeates the campus, like all permeations the traces are so materially and institutionally embedded that they are often invisible. While my project was never concerned with Princeton as such, this omnipresent invisibility struck me as a symptom of larger unanswered questions about architectural postmodernism. How is it, for example, that despite the importance of history to postmodernists, postmodernism in architecture has been subject to little historical scrutiny? Is it possible that postmodern architects produced so much ‘history’ that they used up the field’s history rations, so to speak? Were they borrowing from the future the way that developers of that period traded air rights to control future speculation by proleptically laying claim to hypothetical space? Is this why it has been difficult to think about the postmodern in terms that are not themselves already postmodern? In turn, is this overdetermination why signs of postmodernism, from shapely roofs to color to populism to the appropriation of various stylistic historicisms, are returning to architectural production almost without notice or comment?

These questions reflect the ways in architects, historians and theorists paradoxically deployed a surfeit of words to produce a deafening silence, or what I now think of as the result of a strategic historical effort to make a history impossible to write in the future. This procedure began to take shape in the late 1960s when architects started to turn their attention to making more and more things that did not function like traditional architectural objects from books to TV shows and from teapots to exhibitions but that did require more and more explanation. The paradox is revealed in this context because as they increasingly asserted that such objects, precisely by virtue of their explicitly non-architectural character, proved the existence of an essential architectural condition, autonomous from materials, labor, economies and other concrete relations, words failed them and they resorted to invoking the magically self-defining notion of “architecture itself.” This phrase is still invoked by architects of many different ideological and formal inclinations. In the book I argue that these architects are united only by the lack of awareness that the phrase offers not proof of the existence of some ahistorical category called architecture but rather of the ongoing, if unacknowledged, effects of postmodernization.

How has your project developed or changed throughout the research and writing process?

The project began as an exhibition held at the Canadian Center for Architecture in Montreal, which tried to capture these often small-scale artefacts as modes of production important to architects who identified themselves as postmodernists. The exhibition supported my effort to think of these architects’ work products not as objects of art but as forms of evidence. The show was organized around the networks of things that are so well revealed by the material adjacencies afforded by exhibition environments. For example, in the exhibition space, showing an architectural model made by an architect not only highlights the object’s history as an artifact created in order to present a project to a client, but also highlights the ways in which it was made deliberately to resemble a sculpture that could be exhibited in a gallery and eventually acquired by a collector. Placing this architect’s model next to a model representing the same project but made by an anonymous member of a museum staff because the institution could no longer afford to acquire architectural models that had been redefined and revalued as works of art, demonstrates the historical dynamics that objects capture so well.

I encountered other issues during the curatorial process, however, that required more narrative driven forms of argument, and consequently the catalog morphed into something a bit more like a book. For example, over the course of the research phase I became increasingly disinterested in the kinds of claims made about history by architects who wanted to be seen as postmodernists, and more interested in the concrete means by which those historical claims were made. Robert Venturi, to take a case in point, generally began his ‘design’ work not with the typical sketch of a building made in a sudden burst of genius but with a methodical plan for conducting historical research: a pad of yellow lined paper with notes about what he wanted to consult in the library. The legal pad, like the sketchbook used by artists and architects since the invention of paper, was portable. However, this lined paper was developed for bureaucratic note taking and encouraged the kinds of marks on paper associated with research, meeting memoranda, and instructions to office staff. Nevertheless, the legal pad moved easily from library to office desk to building site, and enabled all these elements, including visual representations, to be drawn together into a new communication environment.

Similarly, Mary-Ann Ray, another Princeton alumna, went to Hadrian’s Villa to learn not only about Roman architecture but also to re-enact the historical process of making drawings of archaeological remains, following in the steps not only of Piranesi but of her Princeton instructor Michael Graves. She became entangled in a series of technological shifts that moved from the chains used as measuring devices in the 17th century, to photographs, digital notepads and eventually to 3-D digital models, or images organized around points in three-dimensional space derived from a semi-analog GPS system.

Why should people read this book?

Like the process that produced it, the book combines curatorial and scholarly techniques in order to make historical arguments. This approach is most evident in the book’s design. Rather than have two numbering systems in the text–one to refer to illustrations that demonstrate and another to refer to footnotes that argue–a single series of refences brings these modes of evidence together, inflating and deflating the traditional hierarchies between them. Sometimes documents that would normally be referred to in a footnote via a file number in an archive are instead reproduced at full scale just as certain kinds of technical artefacts are presented as illustrations. The result, I hope, is an entirely unexpected and less heroic view of the work of well-known architectural postmodernists. It is also an equally unexpected but more interesting view of the concrete relation of things that undergirded not only those architects’ work but also a much wider network of people, machines, institutions and geographies. Furthermore, the book offers a vast and diverse array of material that is presented more like an archive than either an exhibition catalog or scholarly period study: material that is intended to be available for further research. Anyone interested in architectural postmodernism will find threads not followed, links not made, and hence paths both into and out of the myth of architecture itself and through the still permeating effects of postmodernization.

Learn more about other recent publications by Princeton University faculty in the Humanities by exploring our Faculty Bookshelf.