By Miqueias Mugge (Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies), Isadora Moura Mota (History), and João Biehl (Anthropology)

A Rapid Response Magic Project of the Princeton University Humanities Council, Freedoms/Liberdades is bringing together an interdisciplinary group of Princeton and Brazilian scholars to analyze images depicting slavery and freedom in out-of-the-way places across Brazil and write collaborative essays on these representations. Of the 12 million enslaved Africans brought to the New World, almost half—5.5 million people—were forcibly taken to Brazil as early as 1540 and until the 1860s. Brazil was the last country in the West to abolish slavery in 1888. Depictions of enslaved people in numerous media circulated widely in Brazil and internationally. Surviving in multiple archives, these images convey the power dynamics and human values of slave-owners and publics, the certainties and ambiguities of artists and authors, as well as the suffering and agency of the objectified alongside their own sense of freedom.

Over the summer, our Princeton/Brazil research team mined digital collections within Firestone Library’s Rare Books and Special Collections, while identifying images from archives and museums across Brazil. We also held two online meetings and, together, produced eight short essays, now available both in Portuguese and English. Topics discussed included Afro-Atlantic conventions in the portraiture of Black nurses, the interface of African slavery and European immigration, and aesthetics of freedom in post-abolition life.

Six additional Afro-Brazilian colleagues—social scientists, artists, and art curators—joined our team during the summer. We organized a Zoom workshop in late August to discuss data visualization strategies, and will organize another in mid-September to discuss new visual essays on maroon communities, urban black spaces, and black military service.

Below, members of our team provide insights into images from our project.

Lilia M. Schwarcz (University of São Paulo):

The enslaved nanny Mônica, richly dressed, exudes a strong, dignified presence. The image bears a world of contradictions. The greatest of them is the nanny’s tense expression, her hand clenched on her lap, perhaps trying to curb the slightest twitch from “her” boy who is leaning up against her. Missing in this scene and in all the images constructed around the figure of the black nanny are her own children. This absence is absolute here, and an uncomfortable silence hangs over the carefully arranged tableau.

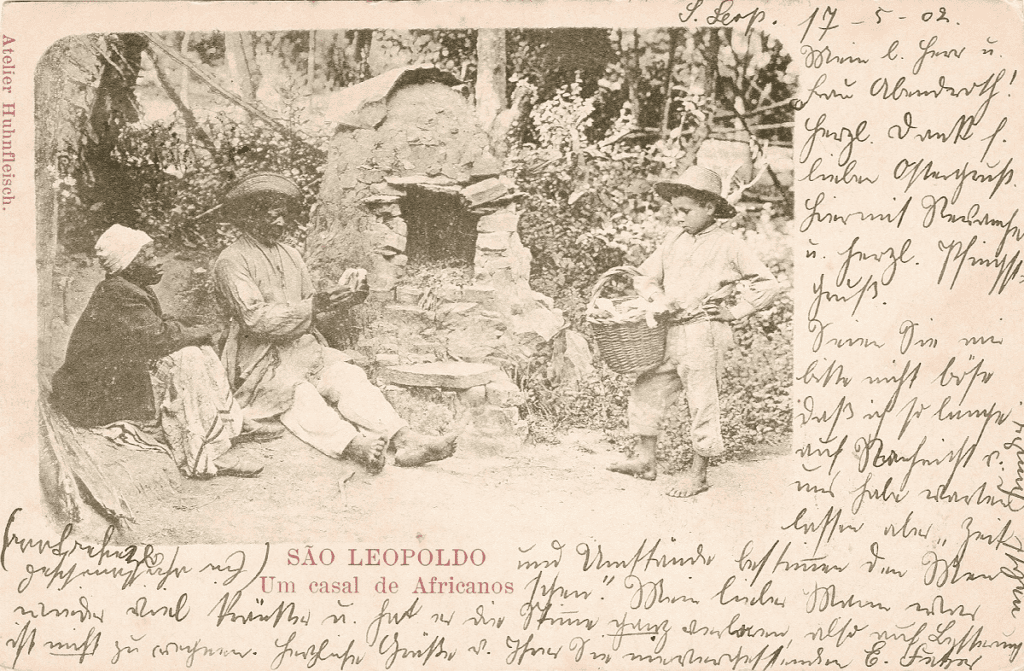

Miqueias Mugge (Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies):

This photograph-turned-postcard was published in southern Brazil in 1902. The unnamed and recently freed couple pose in the area around their home, observed by a working boy who avoids the camera. Lunara’s portrait bucks the trend to portraying an exotic, peripheral “other,” disconnected from the modernity the white descendants of European immigrants sought to embody. The text inscribed in the naturalized postcard reads:

My dear Mr. and Mrs. Abendroth!

Thank you very much for your Easter message. My warmest wishes for Pentecost.

Please do not take offense at my not having sent word in so long; “time and circumstances define people.” My dear husband has fallen very ill again and has completely lost his voice, no recovery being in sight. Affectionate regards from your own, who have not forgotten you, E. F. Friedrich.

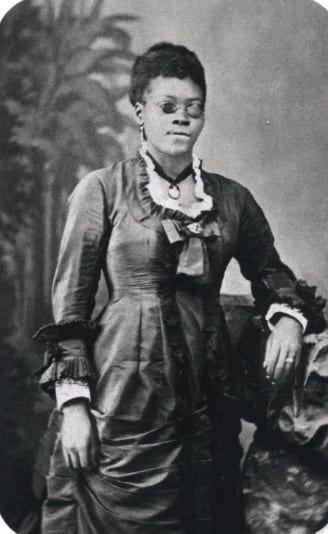

Luciana Brito (Universidade Federal do Recôncavo Baiano):

Unlike the photographs of enslaved women, which circulated as postcards, representing exotic Brazilian images in Europe, the freed and free women photographed by Augusto Militão had other choices—or at least more options, though the “choices” might not have been wholly theirs. Bare arms, low necklines, turbans, and instruments of work such as tabuleiros (the trays on which women street vendors often sold their goods) gave way to other emblems of female respectability. In this 1875 portrait, no detail, with the exception of the woman’s own body, points to what we might imagine as “typically African.” The dress stands out in the photograph: lace, ribbons, and frills demonstrate refinement, and, along with the ring, indicate that the woman is (or desires to be) recognized as someone who is inserted into free Brazilian society. In other words, she is not enslaved.