With a performance that served as one of the kick-off events for the Being Human Festival 2019, Belonging(s) in Movement celebrated indigenous and immigrant tales from the Americas. Spanning October 11 – 14, three days of activities presented by the Department of Spanish and Portuguese included readings, spoken word, and traditional storytelling. Artists and activists visited from Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, in Canada to discuss their Newcomer Zine Project and its iteration in Princeton.

Below, a graduate student and an undergraduate student from Princeton University recount their experiences of the festivities.

Breathing Life into “A Soulless Place”

By Vero Carchedi, 3rd-Year Graduate Student in Spanish and Portuguese

Belonging(s) in Movement centered different historical and contemporary relationships to territory, belonging, and movement by placing indigenous and newcomer/migrant stories from the Americas in conversation with one another. Over the three days, we chose to offer an alternative form of exchange to the free trade agreements of the Americas that privilege the mobility of capital and commodities over that of human beings.

The series opened on Friday, October 11 with an evening of multi-lingual performances by academics and organizers, drawn from Princeton University community members and visitors from Saskatoon and Albuquerque. The night’s location, East Pyne Hall, bears its own entanglements with histories of transatlantic slavery and settlement on un-ceded Lenni Lenape territory.

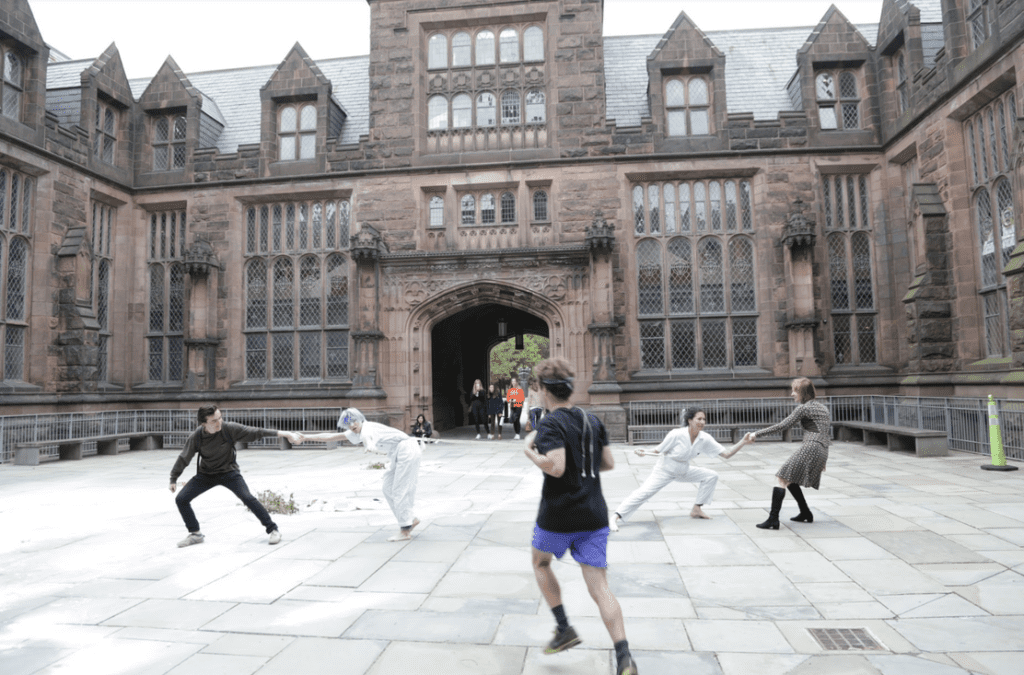

The opening performance by the Do-Mystics was in many ways responding to the 2005 letter in the Princeton Alumni Weekly magazine by Gisela Kam, a cataloguer at Firestone Library, titled “A Soulless Place,” which describes how East Pyne’s courtyard was built over a garden, uprooting its poplars, ferns and various inhabitants. The performance, which took place in the same courtyard, brought garlands of foraged stinging nettle among other leaves and vines, an homage to what was once rooted there. The performance itself—as Monique Blom and Arantxa Araujo became silent, moving statues that occupied the courtyard—answered the question: What does it take to stop, slow, interrupt and disrupt the circulation of bodies and the speed of productivity at Princeton? A group of people gathered and witnessed, a pensive and active silence blanketing the space. A runner crossing the courtyard stopped, pulled out his headphones and sat on a bench to watch the performance, and stood up to intervene in a staged tug-of-war between the two performers. At its end, the performers prompted a collective lead-in to the building, as witnesses stirred the dust (literally, dispersed by the performers), activating the “soulless place.” This palimpsestic intervention breathed life into the “dead stone” of this settlement and opened into readings that meditated on the living present and presence of colonial legacies, and on life that grows through their cracks.

The readings that followed contemplatively bridged past to present, not-here to here, silenced to voiced. University of New Mexico Assistant Professor of Spanish and Portuguese Angelica Serna Jeri presented a short story, “Ñawpapachamanta Rimanakunata Uqllanapaq,” in Quechua, Spanish, and English, on finding home in spirituality and language, and on the untranslatability of the indigenous Andean language, as in kunununuy, the onomatopoeic verb in Quechua, the sound produced by the movements of the earth. Princeton University Spanish and Portuguese fourth-year graduate student Andy Alfonso’s debut performance of his poem “Epitafios insólitos: poemas de (sobre)vida para imaginar el silencio” confronted the dominating and denominating eye of Columbus as one of its interlocutors. Princeton University Associate Professor of Spanish and Portuguese Christina Lee pulled from her pocket the folded trace of “Mi último adiós,” an anti-colonial poem left by Filipino nationalist and revolutionary José Rizal to his wife and daughter before his execution in 1896 by the Spanish Army.

The Director of the Spanish Language Program at Princeton University, Alberto Bruzos Moro, read from A Seventh Man, engaging in a play with time as he connected through images the continuities of immigration, exploitation, imperialism, and capitalism that John Berger and Jean Mohr discuss and photograph in 1975 to today. Princeton University Professor of English Sarah Rivett shared research that serves as a recuperative gesture of Tlingit objects stolen by Presbyterian ministers in Alaska, and decolonizes the symbolism of the raven through a Haida poem from the Pacific West. Mariana Bono, Associate Director of the Spanish Language Program at Princeton University, performed as a call-and-response Guillermo Gómez Peña’s “Lección de geografía finisecular en español para anglosajones monolingües” (“repite conmigo … Mexico es California / Marruecos es Madrid / Pakistán es Londres”). Princeton University Lecturer of Spanish and Portuguese Rafael SM Paniagua, after showing a performance by Peruvian artist Daniela Ortiz who moves a floral offering from Columbus’ monument in Barcelona to the city’s migrant detention center, offered stories recorded of child migrants in Spain on strips of paper wrapped around carnations.

After the readings, the artists from Saskatoon—Michael Peterson, Manuela Valle-Castro, and Chris Morin—read from zines that migrants had written and drawn through their Newcomer Zine Project, thought of as a form of reparation and gathering of indigenous and migrant stories. They explained their praxis of co-creating zines and their processes of translation and printing.

Friday’s performances, in their sincerity and pensiveness, disrupted the normal circulation of activities at Princeton by holding space to think about and feel the long histories of the now—the violence, the movements, the displacements, the lingering presences. Through sharing stories, whether ours or ones that have found voice through us, we found the openings and interruptions of colonial legacy of this day.

Stories of Departure, Arrival, and Change

By Peter Schmidt ’20

On Saturday, October 12, Princeton students and nearby community members gathered beneath the wooden arches and stained glass of the Chancellor Green Rotunda for a day-long zine workshop dedicated to the value of immigrant narratives and free cultural exchange. Many of the community members had heard about the workshop through English as a Second Language programs, and arrived with bags full of fabrics, photographs and coins from far-away homes.

Self-published and easily replicable, zines come from a long cultural genealogy including revolutionary pamphlets, feminist manifestos and punk art. They are easy to produce and distribute, and for that reason are a perfect medium for personal narratives and marginalized voices. They can take any number of forms, and obey almost no strict conventions—some of the zines strewn across the wide table were in Arabic, some in Spanish, some in Mandarin, and some had no words at all—but each told stories of departure, arrival, and change.

The facilitators, Chris Morin, Michael Peterson, and Manuela Valle-Castro, who identify as First Nation, Métis, and Chilean, explained their common belief in the power of art and narrative exchange to enable and enact personal and social change.

To commence the workshop, Manuela opened up a space for each of us—students and community members alike—to share why we were there, what stories we hoped to tell, and what questions we were living with. Many spoke candidly of their past, and a few spoke for nearly a half hour, in English or Spanish.

Once we had heard from everyone, Chris and Michael walked us through the zine production process: cutting and folding printer paper, scanning photographs, composing collages, and then putting all the pieces together. Following the workshop, Chris, Michael, and Manuela would take our fragments back to their press in Saskatoon, where they would scan, print and bind the zines, and then send many back.

We spent the rest of the day scribbling and experimenting. The woman seated next to me incorporated a tiny flag from her country of origin, as well as a number of photographs, textiles, and illustrations. No two zines were the same.

To be part of a creative cycle, where I had the privilege of knowing every person in the zine-making process, made me wonder about the extent to which creativity can be a process of community, rather than of individuals. For eight hours in a sunny room in October, a dozen strangers sat talking and laughing, feeling safe in the small world we had made for one another.