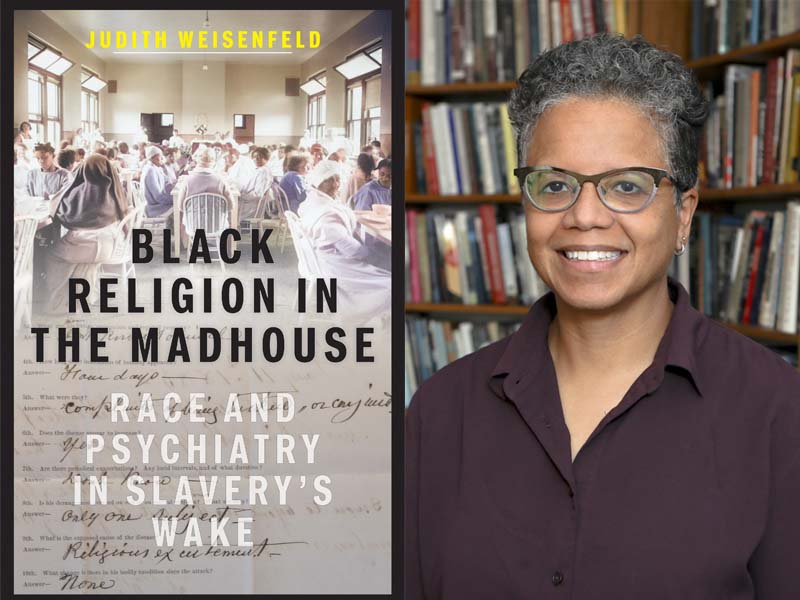

Judith Weisenfeld is the Agate Brown and George L. Collord Professor of Religion and chair of the Department of Religion. Her latest book “Black Religion in the Madhouse: Race and Psychiatry in Slavery’s Wake” was published in April 2025 by NYU Press.

How did you get the idea for this project?

This project emerged from my last book, “New World A-Coming: Black Religion and Racial Identity during the Great Migration,” in which I explored the entanglement of religious and racial identities in Black new religious movements in the early twentieth-century urban North. In researching how New York City authorities responded to Father Divine, whose followers hailed as God, I read several psychiatric studies published in the late 1930s assessing his followers’ sanity. These psychiatrists grounded their evaluations of Divine’s followers in broad claims about “race traits.” They cited late-nineteenth century studies in which southern white physicians proposed that religious dispositions, such as innate superstition or religious emotionalism, were key to understanding African Americans’ mental health and to forecasting their future in the United States. I was curious about the role ideas about Black religions played in theories about race and mental illness in the broader field of early American psychiatry.

How did the project develop or change throughout the research and writing process?

The history of psychiatry was new to me, and I had no idea what I would find in pursuing the question about early white psychiatrists’ theories about Black religion. Early in the research process I imagined that this would be a story of white doctors as secular, scientific authorities evaluating and pathologizing African Americans’ religious beliefs and practices. As I worked to find out more about the lives of early white psychiatric theorists of racialized understandings of religion and mental health for African Americans, I found that many of them had been enslavers of Black people or had come from enslaving families and that most were active members of mainstream Protestant churches. The story that developed became, in part, about the persistence of Christian sensibilities in their psychiatric theories and how their medical practices of care were often about disciplining what they viewed as racialized excessive or improper religion rather than religion in general. Because the material preserved in archives privileges white religious, political, legal, and medical authorities, bringing into view the stories of Black patients committed to state mental hospitals and subjected to such disciplining posed a challenge that required some research tenacity and care in writing.

Why should people read this book?

In foregrounding race and religion in the history of early American psychiatry, the book adds to the literature on medical racism that has been critical for understanding the origins and sources of disparate treatment and patient outcomes in a variety of areas. It is also a story of African Americans’ religious creativity and spiritual strength in the face of enormous challenges in slavery’s wake, including physical and mental illness as well as a medical world that pathologized their spirituality.

Learn more about other publications by Princeton University faculty in the humanities by exploring our Faculty Bookshelf.