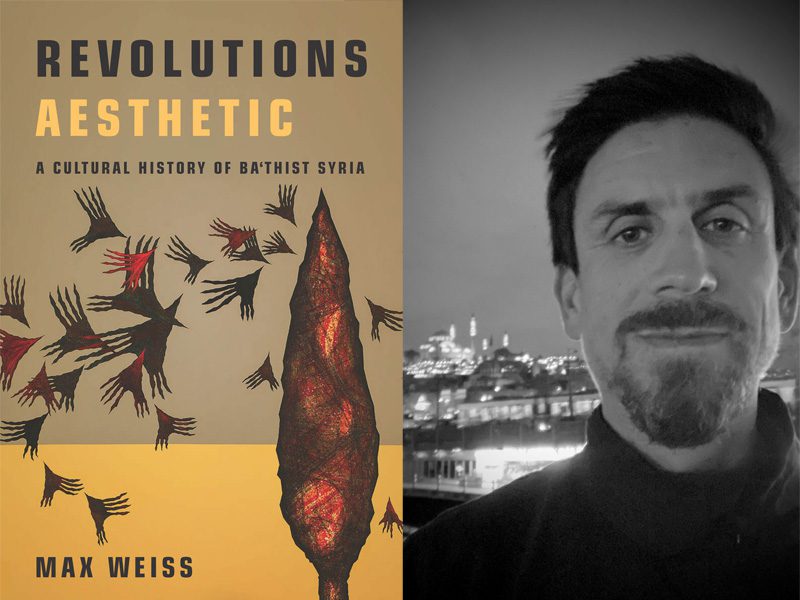

Max Weiss is Associate Professor of History and Comparative Literature. His book “Revolutions Aesthetic: A Cultural History of Ba`thist Syria” was published in June 2022 by Stanford University Press.

How did you get the idea for this project?

“Revolutions Aesthetic” is a cultural and intellectual history of Syria under Ba`th Party rule, or, more precisely, during the regimes of Hafiz al-Asad (1970-2000) and his son, Bashar al-Asad (2000-present). The book emerged organically from my work as a translator of modern and contemporary Arabic literature into English. It was through reading, translating, and writing about these works that I began to take notice of just how dynamic the relationship between aesthetics and politics has been in the making of contemporary Syrian culture, specifically in the novel and in film, another longstanding interest of mine. I became increasingly fascinated by how certain conceptions of the political—indeed, struggles over the form and content of the political itself—were in this space of writing and filmmaking. This, in turn, led me to think more carefully about what historians can learn from and do with cultural production as historical sources.

In the book, I argue that the construction of state power in Syria was a complex and contested process, shaped, in part, by what I call an agonistic struggle around aesthetic ideology throughout this period, especially the aesthetic ideology of what I call Ba`thist cultural revolution, which accompanied and defined the capture of the state by Hafiz al-Asad in a coup dubbed a “corrective movement” in November 1970. Rather than accept or reproduce the facile notion that the Syrian state has been totalitarian in its nature and effects, I guide the reader through a broad range of prose writing, films, and cultural periodicals that reflect an underappreciated margin for independent creative expression and resistance to state power in the cultural field but also demonstrate the difficulty, at times, of discerning the differences between what is too often reductively categorized as “state culture” and “dissident culture” or “resistance culture.” This intellectual-historical approach to cultural history, literary studies, and film criticism allows me to draw attention to the complex relationships connecting a number of actors: state publications such as literary, intellectual, and cinema periodicals published by the Ministry of Culture; state-authorized associations, including the National Film Organization and the Arab Writers’ Union, two of the leading organizations for filmmakers and writers, respectively; and, the lives, thought, and work of a broad range of prose writers, public intellectuals, journalists, activists, filmmakers and other artists.

How has your project developed or changed throughout the research and writing process?

Dramatically. When the Syrian uprising began in Spring 2011, I was enervated, like many others, by the courage and creativity of ordinary Syrians as they struggled to “break the fear barrier,” as many put it at that time, in order to express their demands for life, liberty, and dignity, three keywords of this revolutionary upsurge. When I was able to visit Syria during summer 2011, I was profoundly affected by coming face to face with the swirling forces of unrest but also the gathering clouds of counter-revolutionary reaction that were already discernible during those early days. My modest scholarly contribution in “Revolutions Aesthetic” pales in significance compared with the cataclysmic scale of human suffering and loss that is the true tragedy of the Syria War as it unfolded in the aftermath of the uprising: over a half million dead and nearly half of the Syrian population internally displaced, made into international refugees, or otherwise forced into exile. Like many scholars of Syria—and nearly half of the country, which was either internally displaced or forced into exile—it became difficult if not impossible to visit the country, which required a fundamental reconsideration of what kind of scholarship on Syria would be viable and meaningful. At this point, my translation work became an even more crucial means for me to engage with the situation in Syria. Moreover, my experience of translating non-fiction and fiction—perhaps most crucially, Samar Yazbek’s “A Woman in the Crossfire: Diaries of the Syrian Revolution” (a memoir) and Nihad Sirees, “The Silence and the Roar” (a novel)—showed me just how substantially the relationship between aesthetics and politics had evolved over the course of the first decade of the twentieth century and alongside the dizzying events of the Syria War. It was particularly striking—and not just to me, of course—how effervescent the Syrian literary and cinematic spheres became during this period, in the real time of war. I wanted to situate those developments in historical perspective, which is why the last two chapters of the book as well as the epilogue deal primarily with cultural production from the time of Syrian uprising and the Syria War, while also addressing the possibilities that literature and culture might present for thinking about postwar reconstruction.

What questions for future investigation has the project sparked?

I hope that this book makes a contribution to opening up new pathways for multidisciplinary work in Middle East studies. The destruction and persistent inaccessibility of archives as well as other historical materials in Syria (as is the case, unfortunately, with respect to a number of other locations around the region) will continue to complicate the research agenda of scholars. At the same time, this set of methodological challenges might also create new opportunities for different kinds of multidisciplinary research and scholarship. My interests in modern Middle East studies bring together intellectual history, comparative literature, and film studies. In addition to solidifying my conviction that literary translation is not simply an instrument for pursuing the historian’s craft, I came to realize that historians of the modern Middle East still have a great deal to learn—methodologically but also in terms of the analytical questions one might ask—from these adjacent disciplines. Prior to writing “Revolutions Aesthetic,” I had been on work on a book about modern Syrian intellectual history. Not only am I buoyed by having finished this book and excited to see what kinds of conversation it might catalyze, but writing “Revolutions Aesthetic” has also inspired me to write intellectual history in a manner that will foreground literature, film, and other forms of cultural production as articulate historical sources.

Why should people read this book?

If the Syrian revolution and the war that followed have attracted substantial international attention in terms of geostrategic military analysis and humanitarian concern for the shocking displacement, destruction, and human suffering that has ensued, the cultural consequences of the revolution and the aesthetic dimensions of cultural production in the time of the war have attracted less attention. Revolutions Aesthetic provides a broad but also detailed survey of Syrian literature, film, and culture that has not been accessible to an English-language readership. Readers are introduced to these materials through close analytical readings and, I hope, find unique perspectives on and insights into the country’s recent cultural, intellectual, and political history along the way.

My hope is that anyone interested in understanding the relationship between state power and cultural production will read this book; certainly, anyone interested in the making of modern and contemporary Syria as well. Broadly speaking, those with interests in the relationship between culture and politics, how state power affects the cultural sphere, and how writers, artists, and filmmakers engage with questions of politics and aesthetics should find much food for thought in this book.

Learn more about other publications by Princeton University faculty in the humanities by exploring our Faculty Bookshelf.