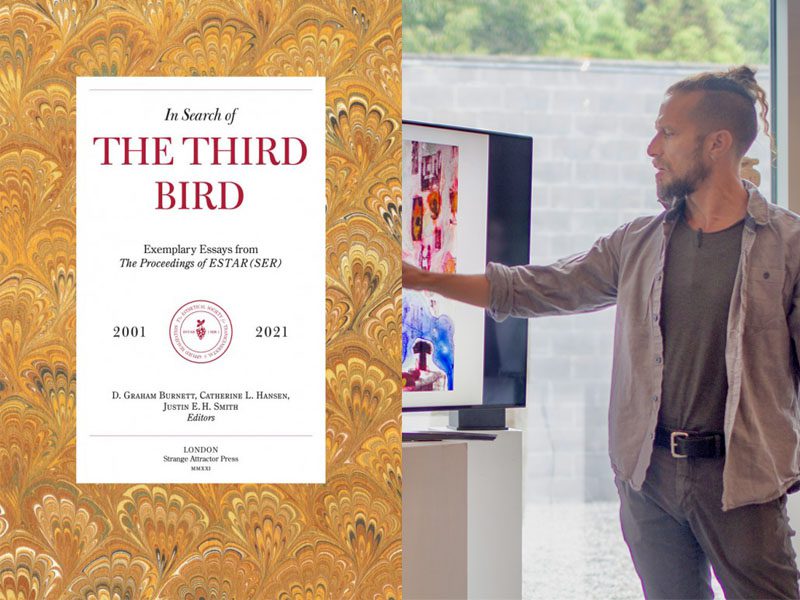

D. Graham Burnett is Professor of History and History of Science. His book “In Search of The Third Bird: Exemplary Essays from The Proceedings of ESTAR(SER), 2001-2021,” which he co-edited with Catherine L. Hansen (University of Tokyo) and Justin E. H. Smith (University of Paris), was published in December 2021 by MIT Press. A longer interview about this project can be found in the Journal of the History of Ideas.

How did you get the idea for this project?

This is an unusual book — the product of many years of intensely collaborative work by several dozen artists, writers, and scholar-dreamers from half a dozen countries. I cannot really claim the “idea” for the book as exactly “my own” in such a context! In a basic way, its origins lie in shared time and thought. From the start (decades ago in some cases) a number of us were working together on “attention” in different ways: the changing technical history of attentional practices; attention as a literary theme or problem; attention as something like a “medium” in the work of some contemporary artists; attention as a way of rethinking the philosophy of aesthetic experience.

We began to experiment with new techniques for creating space to engage these issues, and to reflect upon them. Some of the research we presented in university environments, but more and more we found ourselves doing this work in museums and galleries — and eventually the project found its home in the ecology of contemporary art, as a kind of “imaginary academy” known as ESTAR(SER) – or, the “Esthetical Society for Transcendental and Applied Realization (now incorporating the Society of Esthetic Realizers).” Our inspiration lay in the “Collège de ‘Pataphysique” and “OuLiPo” and Walid Raad’s “Atlas Group,” as well as other forms of what has come to be called “artistic research.”

Gradually, we started to make texts together, and to give presentations that took the form of participatory “performance lectures,” a genre that interested many of us in the group. At the heart of the project was the problem of ATTENTION, an issue we saw as charged with immense contemporary importance in the context of the emerging “attention economy.” But we were also exploring the relationships between scholarship and play, knowledge and poetry, pedagogy and theater.

How has your project developed or changed throughout the research and writing process?

The work on this book has been a totally life-changing unfolding of friendships and invention and discovery — for me, anyway. And I think some of the others involved would say similar things. My co-editors, Justin E. H. Smith (a professor of philosophy in Paris), and Catherine L. Hansen (who teaches literature at the University of Tokyo) were friends to start with, but across this project we have spent countless hours reaching together toward a shared dream. This has been very special.

And along those lines, I would count many of those who co-authored the different chapters of the book among my deepest intimates. Much of the power of these connections can be traced to the way this book emerged out of a back-and-forth between actual “practices” (of attention, of archival exploration) and phases of (collaborative) research and writing and “staging” of our work. Most of the chapters in the book had their origin in various workshops and residencies where groups of us would hole up for an intensive week of reading and writing and experimentation. In many cases, those weeks would culminate in some form of theatrical “charette” or public performance. We pushed each other in those settings — and the audiences pushed us too. We failed some of them, for sure! But we learned so much from the specific pressures of “going live” with roomfuls of human beings, who might or might not care about what we wanted to do.

All of us owe a special debt of gratitude to the institutions that gave us those opportunities. I am thinking here of places like Mildred’s Lane (run by the artists J. Morgan Puett and Mark Dion), the Emily Harvey Foundation (in New York), Le Confort Moderne (in Poitiers, France), and, more recently, Robert Wilson’s extraordinary Watermill Center (out on Long Island). Curators, too, gave us key venues in which to show our work as it emerged: at MoMA’s PS1 and the Guggenheim (both in New York), at the Palais de Tokyo (in Paris) and the Tamayo Museum (in Mexico City), and at a number of biennials, like Manifesta (Zurich) and São Paulo (in Brazil). Finally, there were the universities that gave a number of us chances to teach and present as we developed our thinking: I taught or co-taught several graduate seminars at Princeton on related topics over the years (“The Art of Deception: Aesthetics at the Perimeter of Truth” in 2011; “Matters of Attention” with Sal Randolph in 2013; “The Enacted Thought” with Chiara Cappelletto and David Levine in 2016; and “The Poetics of History” with Jeff Dolven in 2019), and other universities, too (like the Universität der Künste Berlin, and the ETH in Zurich, and the Universidad Torcuato Di Tella in Buenos Aires), supported important phases of the project.

What changed across all those years? Well, I think our understanding of what we were trying to do “changed” — we were not setting out to make a book for which there was a single obvious model. Yes, of course, there were lots of precedents and inspirations (from Borges and Cortázar to “The Crabtree Orations” or Jean d’Ormesson’s luminous “La Gloire de L’Empire”), but in another way, we were in uncharted water: we were trying to make a “world,” using the tools of scholarship; we were trying to reactivate the genre of the “mystification” in a post-Google information ecology; we were trying to write a history that took Hayden White’s “Metahistory” seriously; we were trying to create an allegory of a central problem in the historiography of “experience”; we were trying to demonstrate that “scholarly metafiction” could be a form of practice-based research. We had to feel our way to an understanding of these problems, and the way our shared project could address them. Different contributors were more interested in this or that aspect of the wider ambition, but we hammered out jointly-written essays that, together, addressed all of that stuff.

And whatever readers think of the resulting book, the process of making it included, for all of us, I think, moments of joy and discovery and insight that will not be forgotten.

What questions for future investigation has the project sparked?

At the heart of the book is the idea of “the archive” as a certain kind of generative space — a space where the relationship between the past and the present is negotiated. This is by no means an idea original to us. On the contrary, it is a central theme for many kinds of historical inquiry and social analysis. And artists, too, have been attentive to the critical and creative potential of archival environments. The ESTAR(SER) collective has developed its own “idiom” for activating history through an archival poetics. The idiom has its limits, to be sure. But I think we have not in any way exhausted its potential.

With my longstanding colleague and friend Joanna Fiduccia, a professor of modern and contemporary art history at Yale, I recently helped co-curate a large exhibition at the Frye Art Museum in Seattle, THE THIRD, MEANING. This show is a direct extension of the project of “In Search of the Third Bird,” and more than a dozen of the artists and writers are ESTAR(SER) folks who also collaborated on the book. The exhibition is a direct effort to address several of the questions raised by that project. For instance: “How can museums address the shifting ecology of contemporary human attention?” And “What forms of resistance can be cultivated in defiance of the relentless commodification of human attention within the eye-ball fracking economy of our screen-lives?”

A number of us who have been involved in the ESTAR(SER) work over the years have increasingly given our time and energy to more explicitly “activist” engagement with that latter problem, through a community known as “The Friends of Attention.” That group just published a short “manifesto”-like book with Princeton University Press, “Twelve Theses on Attention.”

Why should people read this book?

Hmmmm. This is a hard question. There are a lot of good things to do with one’s time. I am not sure I feel all that comfortable trying to say that anyone “should” read “In Search of the Third Bird.” I love the book. And I think it is a richly-worked thing. I guess I would even say that I think that, under the right form of attention, it can yield up feelings of something like “wonder” — and create a sense of “disorientation” that (again, under the right conditions) can be experienced as… well, as what? As “delicious”? Intoxicating? As “promissory”? I am not sure how to talk well about this.

I think some readers will find the book simply unbearable — as arch, involuted, indulgent. I am able to feel how that reading might feel. But I believe other readers will sense the book less as a provocation (which, in my view, it has no interest in being) and more as a solicitation, a beckoning — an invitation. The book wishes to cast one of those spells in which, for a moment, one catches a glimpse of the way things could be TOTALLY DIFFERENT. Which implies that one could oneself BE totally different. Such a sense, and the return to oneself from such moments, — something very important about being a human being is at stake in those episodes. Our book is about that. And it wants to make it happen, too.

Learn more about other publications by Princeton University faculty in the humanities by exploring our Faculty Bookshelf.