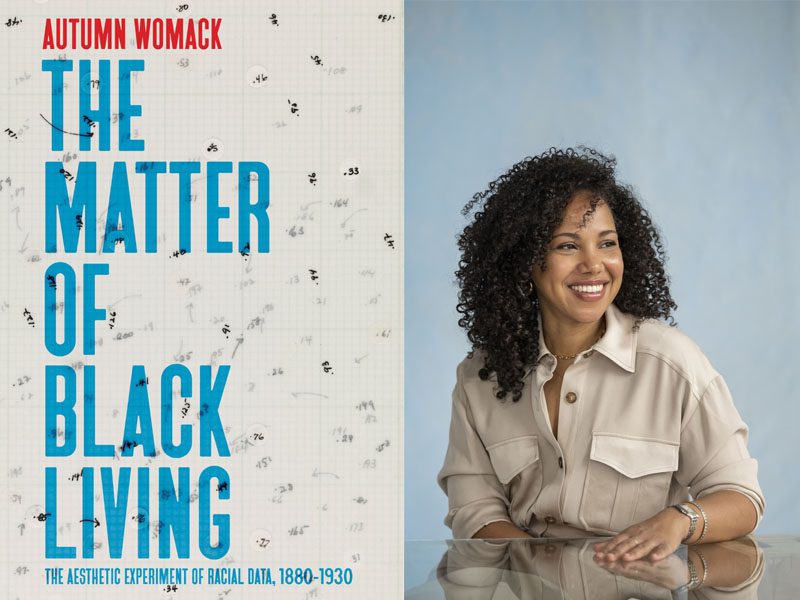

Autumn Womack is Assistant Professor of African American Studies and English. Her book “The Matter of Black Living: The Aesthetic Experiment of Racial Data 1880-1930” was published in April 2022 by The University of Chicago Press.

How did you get the idea for this project?

Interestingly, this book doesn’t have a clear origin story. I never, for instance, set out to write a book about racial data and its vexed relationship to Black expressive life. Instead, this book is the culmination of years of spent thinking about the curious interplay between African American aesthetic production and what we might think of as various kinds of empiricism in the long nineteenth century. When I was graduate student at Columbia University, I was intrigued by the vast number of nineteenth-century Black creative thinkers who also identified themselves doctors, scientists, and mathematicians. Sometimes these were professionally recognized designations, as in the case of W.E.B. Du Bois. But just as often these were self-conferred, as in the case of Dr. Martin Delany who worked across the domains of fiction and science in the mid-nineteenth century. Eventually, this simple observation developed into a broader question, one that had particularly high stakes for turn of the century African American intellectuals and cultural producers. How, I wondered, did African Americans understand the enduring, and often violent, relationship between Black life and data regimes? This question, I realized, was particularly weighty at the turn of the twentieth century, a moment when a host of new data producing technologies and empirically driven discourses were summoned to address the ever-pressing question of Black freedom in the aftermath of emancipation. As I continued to research, it became clear that even as racial theorists, social scientists, and reformers were harnessing statistics, social surveys, and new visual technologies to capture information about Black life in the name of solving it, like their antebellum antecedents, African American intellectuals, reformers, and performers were also investigating the relationship between data and Black life. And it was this story that I was interested in telling and investigating, a story about how Black cultural producers intervened into this data regime in ways that had surprising outcomes.

How has your project developed or changed throughout the research and writing process?

Data was not originally one of the books keywords. As someone with a background in Literary Studies and American Studies, I initially felt ill-equipped to take on such a huge keyword. When I was in the final stages of manuscript writing, I visited a seminar at Haverford College where students were reading an article that I had written on Zora Neale Hurston and film, which would become the books third section. In the midst of our discussion, a student asked a question about a turn of phrase, “un-disciplining data,” which I had used to describe the unintentional impact of the filmed subject’s confrontation with the filmic technology itself. At that moment it became clear that although I wasn’t discussing data in the traditional sense, the project was invested in exploring the technologies, forms, and mediums that produce data about racialized bodies. This expanded notion of data cracked something open and became the book’s connective tissue.

What questions for future investigation has the project sparked?

“The Matter of Black Living” ends by considering the filmic and gestural grammars that animate Zora Neale Hurston’s seminal essay “Characteristics of Negro Expression” (1934). This was the very last piece of the book that I wrote and so it naturally anticipates many of the questions that I am taking up in my next project, tentatively titled “A Speculative History of Black Film.” In this section, I argue that Zora Neale Hurston’s late 1920s experiments with film and filmmaking doubled as an aesthetic rubric for the theory of black gesture that she sketches in “Characteristics.” I’m fascinated by what the interplay between black literary work and film might reveal about a theory of Black cinema, one that exists in the moments of translation and mistranslation between filmic technology, Black life, and literary text. As part of my research I also kept encountering black writers who doubled as filmmakers, or black writers who quietly adapted their writing into screenplays, most of which were never produced. I’m excited to pick up this thread that I began to unravel toward the end of “The Matter of Black Living” and see where it guides me.

Why should people read this book?

This book certainly has its center of gravity at the turn of the twentieth century, but it’s also a book that asks us to rethink the relationship between race and data that we’ve inherited. This is a relationship that continues to assume that data regimes can represent Black life and that data will solve racial “problems.” The book concludes by asking us to consider how attending to different genealogy of race and data, one that does not take for granted their computability, might point us toward more just futures. There is perhaps no better moment to take up this charge.

Learn more about other publications by Princeton University faculty in the humanities by exploring our Faculty Bookshelf.