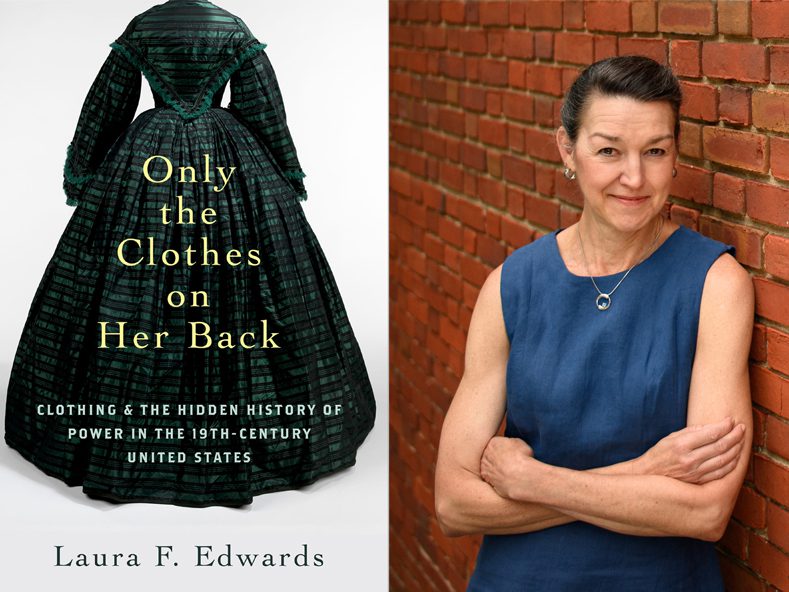

Laura Edwards is Class of 1921 Bicentennial Professor in the History of American Law and Liberty and Professor of History. Her book “Only the Clothes on Her Back: Clothing and the Hidden History of Power in the Nineteenth-Century United States” was published February 24, 2022 by Oxford University Press.

How did you get the idea for this project?

You could say that this book found me. I have always loved textiles, and that interest inevitably spilled over into my work as a historian, where evidence relating to these goods always distracted me. Even when working on other topics, I took notes on matters relating to cloth, bed linens, clothing, and related accessories, such as hats, shoes, and handkerchiefs. Sometimes I would stop and wonder why; sometimes I did not notice at all. But that material accumulated over time and ultimately came together in the outlines of this book, one that I never set out to write. But it has been a pleasure to write, not just because of the topic, but also because of what textiles reveal about the history of the nineteenth century. They allow us to see forgotten elements of law and the economy—elements based in practices and principles, commonly known then, but now in disuse, which made all kinds of textiles a form of property that people without rights could own and exchange. That mattered, because textiles were still valuable at this time, a fact that, when noted in the scholarship at all, is usually explained in purely economic terms. But the value of textiles depended on law: it was law that turned these goods into a secure form of property for marginalized people, who used them as currency, credit, and capital as well as points of entry into the new republic’s economy and governing institutions. As useful as textiles were, however, they were never just utilitarian. They were also meaningful on other levels, which allow us to see people of the margins in more fulsome—more human—terms. From the vantage of textiles, we can see their love of beauty; their wisdom, humor, and joy; and their creativity and resilience, as they clung tenaciously to fine filaments of hope at a difficult juncture in our nation’s past.

How has your project developed or changed throughout the research and writing process?

In “Only the Clothes on Her Back,” I follow the property claims of people without strong claims to property. Many of these people, particularly free married women and enslaved people, did not have property rights. Others had weak claims to property rights, given their poverty and/or their racial status. Yet the evidence made it clear that these people thought of the textiles in their possession as their own, as did other people, including merchants and the men who held positions of authority over them, including husbands and masters. More than that, people on the margins often had thriving businesses based in the production and trade of these goods. But the scholarship on this period suggested that all that was impossible: the lack of property rights made it impossible to own property or enforce claims to ownership in the legal system. These people’s claims, therefore, were outside the legal system and purview of the state. I spent a lot of time working within that framework, characterizing the rules governing the trade in textiles among people on the margins as “informal” (different from “real” law) and “underground” (different from the “real” economy). But those assumptions were difficult to sustain, because the trade in textiles followed well-known, widely followed rules that were enforced in court. Disputes involving those with weak claims to property rights could not be resolved through civil suits, the usual legal form for property issues, such as debts, because this legal rubric required the claimants to have property rights. Instead, court officials used criminal charges, usually theft, because this legal form did not require the defendant to have property rights. In it, property could simply be returned to its claimant as means of restoring the public order, not the property rights of the affected individuals. I was stunned at one point in the project to realize that property disputes among people without rights were similar to those of people with them: people without rights were buying, selling, saving, loaning, and leveraging their property just like white men with rights, often following similar rules. It was the legal frame used to resolve these conflicts that made these exchanges seem so different. In fact, the people who I thought to be “outside” law and the economy were really inside of it all along.

What questions for future investigation has the project sparked?

This book has sparked my interest in the importance of written documentation as the law developed over the course of the nineteenth century in the United States. Written documentation acquired legal power because of proactive measures that included legislation mandating its use and the building of institutions to manage the resulting work. Those changes marginalized other forms of fixing facts—through orality and customary practice. Scholars have tended to accept that outcome as inevitable. It was anything but. In fact, alternate evidentiary standards lingered into the nineteenth century, although they were increasingly associated with people on the legal margins, an association that tended to further undermine the legitimacy of these forms of evidence. At the same time, the continued presence of those forms of evidence—particularly orality and practice—reveal the persistence of conceptions of property that construed ownership not in terms of individual rights, but in more fluid terms that tended to privilege use and to give family members priority over creditors. I am very interested in thinking more about the shift to written documentation and what it reveals about conflicts over the handling of credit and property that affected all Americans—and still does.

Why should people read this book?

“Only the Clothes on Her Back” tells a very different story about by centering women as the paradigmatic legal subjects. When white men with rights are the standard, presumption is that rights were always necessary to participate in the nation’s governing institutions and its economy. Those without them tend to appear primary as victims in a system that stripped them of the rights and, by extension, power. Our historical narratives are then focused on the efforts to extend rights. As “Only the Clothes on Her Back” argues, those narratives are not so much wrong as they are incomplete. In fact, it is the legal experience of women that are representative of the population generally at this time, not those of the minority of white men who could claim the full range of rights. People with weak claims to rights did not just wait until they had them. They found creative ways to include themselves in their country’s governing institutions and its economy without rights, even as they began agitating for them. They could do so because law and economic relations were not structured solely around rights in that time. In other words, the United States did not emerge from the Revolution with a legal system focused on rights fully formed. The system and the place of rights within it was emerging in this period. By the time of the Civil War, rights were becoming more important in both law and the economy, while the legal principles attached to textiles were fading. There were good reasons for that, as the book shows. But as the book also shows, when you view that development from the perspective of textiles, it is clear that the extension of rights to marginalized groups was even more difficult that the existing scholarship suggests. And, so, as textiles turned into just cloth, the majority of the population was left exposed, without rights and the legal principles that once attached to textiles. The book ultimately has a tragic arc. At the same time, it is a story full of hope, one about the power of people to make meaningful change, even in the most difficult of circumstances.

Learn more about other publications by Princeton University faculty in the humanities by exploring our Faculty Bookshelf.