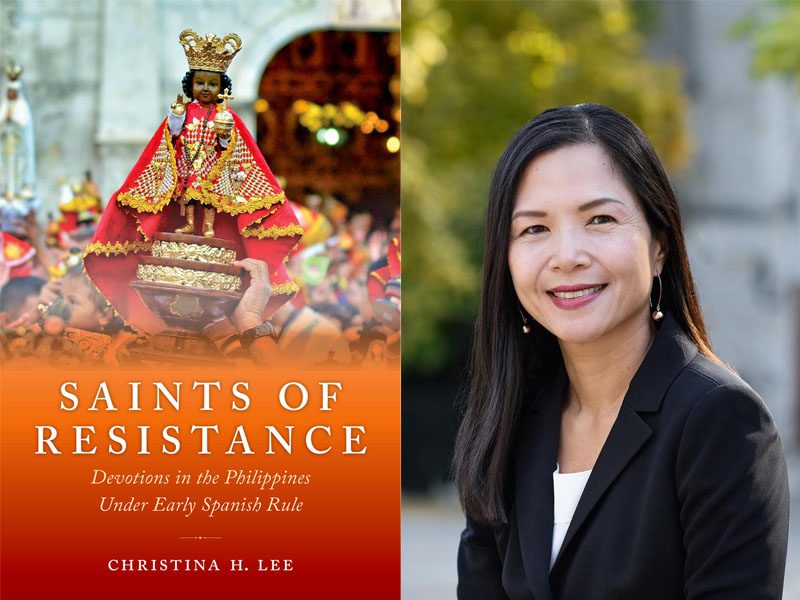

Christina H. Lee is Associate Professor and Director of Graduate Studies in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese. Her book, “Saints of Resistance: Devotions in the Philippines under Early Spanish Rule” was published September 17, 2021 by Oxford University Press.

How did you get the idea for this project?

When I visited the Philippines for the first time in 2015, I was struck by the omnipresence of Catholic sacred images, especially of the figures of the child Jesus and Mary–the saints, that encountered in non-religious spaces, such as airports, restaurants, convenience stores, private homes, government offices, etc. I was well aware of that the Spanish missionaries had introduced the devotions of the saints during the period of Spanish rule, but I didn’t realize that the cult of the saints had such a strong following in the present day. The first thing I did after returning from that trip was to investigate the historical origins of the devotions and I was astounded to eventually find out that some of the most important iconographic cults coincide with the early stages of the Spanish conquest.

How has your project developed or changed throughout the research and writing process?

Once I started delving into the history of the devotions, I learned that some of my intuitions were simply wrong. For example, I learned that the supposed physiognomical features of an image in the pre-modern period did not indicate what we would assume today. For example, indigenous communities revered a Flemish looking image of the Holy Child, but the appearance did not stop them from claiming that the saint had been in their community from times immemorial. In the same vein, one of the most favored images of the Spanish community in Manila was an ivory statue of an East Asian looking Madonna.

What questions for future investigation has the project sparked?

What I learned in my investigations is that the Spanish missionaries and officials had a conflicted relationship with Chinese in the Philippines. They heavily depended on Chinese goods and services while mistrusting their loyalty to Catholicism and the Spanish Crown. Something that made the Spanish colonists deeply uncomfortable was the fact that many of the Chinese in the Philippines, even after Christian conversion, refused to acknowledge Spain as a superior empire than China’s or Spaniards as a higher caste. So, the question I have is how did the Philippine Chinese and non-Chinese get to a point in the eighteenth century in which they bought into the discourse of inferiority? This question is important because it might lead to other ways of understanding the construction of race and racism in early modernity.

Why should people read this book?

My investigations reveal that, in the Philippines of early modernity, the colonized individuals and communities could not be “brainwashed” by people in power to give up their forms of spirituality. Even under the guise of conformity, the subjected found ways of preserving the stories and the core beliefs that gave meaning to their lives. My work is localized in the Spanish Pacific, but I think that readers who study other areas that were colonized by the Spanish and Portuguese empires might be able to benefit from my findings.

Learn more about other publications by Princeton University faculty in the humanities by exploring our Faculty Bookshelf.