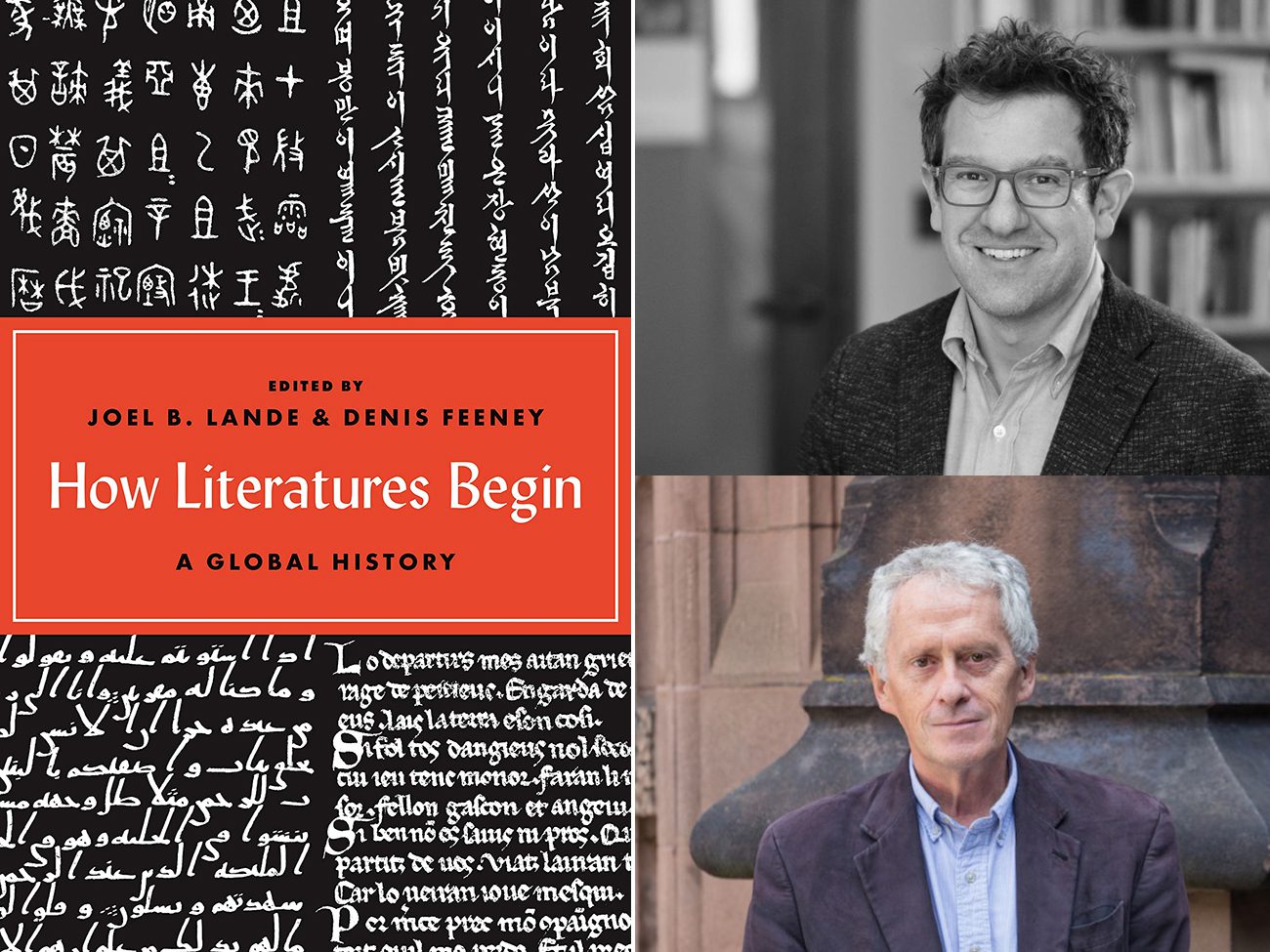

Joel B. Lande is Assistant Professor of German and Denis Feeney is Giger Professor of Latin and Professor of Classics. Their co-edited book, “How Literatures Begin: A Global History” was published in July 2021 by Princeton University Press.

How did you get the idea for this project?

The idea of studying literary beginnings first emerged from our independent research and then really took shape once we together discovered that we had questions we couldn’t answer alone. When we first met in 2011, we realized that we were respectively working on the origins of Latin and German Literature and that comedy (in particular, the early Roman comedian Plautus) played a pivotal role in the formation of both literary traditions. A few years later, our decision to offer a 400-level course on the topic confronted us with our own disciplinary limits and inspired us to organize a symposium on the topic. The surprising fact that literary beginnings had never previously been the subject of comparative investigation afforded us and the other authors an unusual amount of latitude in the design and execution of the project.

How has your project developed or changed throughout the research and writing process?

There was a lot of valuable brainstorming at the Princeton Symposium that kick-started the volume, and some of the big issues of the book came out into the open and were discussed in detail during that day. Not all of the eventual contributors were present at the Symposium, but there was a great deal of synergy even so. Since we were co-editing a volume with studies of seventeen different literary traditions, we were the ones with the synoptic overview, tasked with writing introductions to the four sections of the book, together with an overall Introduction and Conclusion. As each chapter came in, our perspectives would shift in response to the distinctive nature of the new case study. We were more and more impressed by the sheer variety of how “literatures” develop throughout history. In particular, we realized how misleading it was to be guided by default assumptions based on Classical literature. The ancient Greek prototype—an oral phase followed by writing, with widespread reception—proves to be highly culture-specific, and not a “natural” template as it is regularly taken to be.

What questions for future investigation has the project sparked?

Even though the seventeen case studies in the volume provide a good amount of geographical and temporal coverage, there are still some literary traditions that we could not include, but that would raise new and fascinating questions. For example, we think it would be worthwhile to take a closer look at a hybrid and relatively short-lived literary tradition like Yiddish or the aboriginal literatures in New Zealand, Australia, and North America. Studying such literary traditions would give us the opportunity to investigate the related and hitherto little-understood phenomenon of literary demise. As it happens, we understand very little about the endogenous and exogenous factors that lead to the death of literary tradition. Such an investigation would throw further light on the phenomenon of multiple beginnings that is analyzed in a number of the chapters in our book. A literature like Chinese, that is, does not amount to a monolithic and continuous tradition extending back to antiquity, but instead experienced multiple moments of rebirth. It would be fascinating to know whether commonalities exist among different instances of ‘literacide,’ including not only the processes of plateauing or decay, but also the technologies of storage and preservation that make past traditions accessible to us today.

Why should people read this book?

We learnt an enormous amount from working on this book, not only about literary traditions that were new to us but also about the literatures that we specifically study—German, and Greek and Latin. The comparative exercise really came into its own for us in the process. We are sure that readers of the book will have the same experience of being challenged to rethink assumptions about institutions and developments in fields close to them that feel all too natural, but that turn out to be highly contingent and specific. As a result, readers will find themselves thinking in novel ways about what “literature” is, or what “literatures” can be. Not long ago it looked as if the very category of “literature” was no longer of any value, but we hope that readers of the book will find themselves rethinking that assumption as they are introduced to seventeen case studies which are all very different, but which together show intriguing family resemblances.

Learn more about other publications by Princeton University faculty in the humanities by exploring our Faculty Bookshelf.