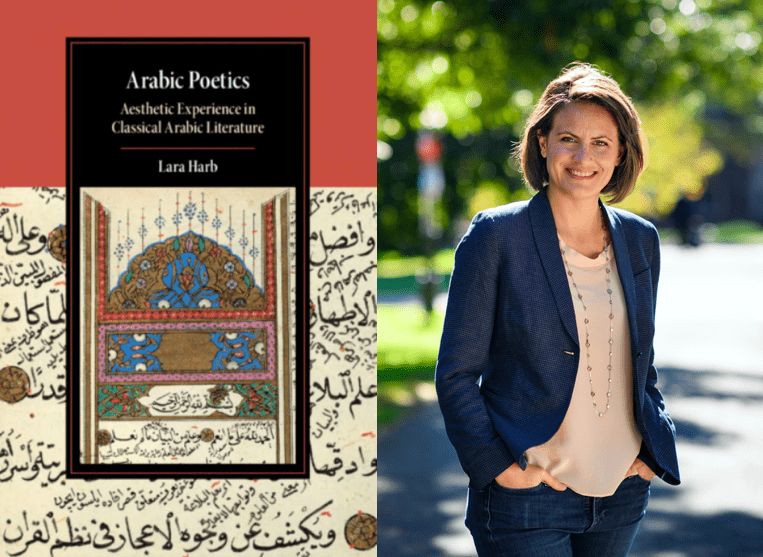

Lara Harb is Assistant Professor of Near Eastern Studies. Her book “Arabic Poetics: Aesthetic Experience in Classical Arabic Literature” was published in May 2020 by Cambridge University Press. This retrospective Q&A is part of an effort to acknowledge all the wonderful books published early in the pandemic.

How did you get the idea for this project?

I was interested in literary theory from when I was an undergraduate studying Comparative Literature. However, most of the theory I was exposed to then was Eurocentric. When I started graduate school in Middle Eastern and Islamic studies, I discovered this whole world of literary theory that was written in Arabic starting from the 8th and 9th centuries CE onward. I also discovered that its sophistication has been greatly underestimated in modern scholarship, even by scholars I greatly respect and admire. Then I was hooked. I wanted to dig deep into these Arabic texts and understand what is going on. Listening carefully and humbly to what the primary texts have to say allowed me to see patterns, assumptions, and ultimately a theory of literary aesthetics. This is what I ended up detailing in my book.

How has your project developed or changed throughout the research and writing process?

I make the argument in my book that the main aesthetic underlying post-10th-century classical Arabic literary theory was one of wonder; that is, poetic beauty was evaluated based on the ability of language to evoke an experience of discovery and wonder in the listener. This aesthetic of wonder, however, is not something described explicitly by the medieval authors. Rather, it is an assumption I argue lies behind the various explanations they give for poetic beauty. When I set out on this project, I was simply asking the question: How did medieval authors assess the beauty of poetry? What criteria did they use? I had no idea what the answer would look like. I came across an important clue when I was studying the Arabic commentaries on Aristotle’s Poetics, which explicitly associated the effect of a poetic statement with wonder. After that, I started seeing wonder everywhere, not just in Aristotelian poetics, but also in treatises on poetry and eloquence outside of the Aristotelian tradition, as well as in works on the inimitability of the Quran. The result showed that there was a comprehensive aesthetic across disciplines in post-10th-century works of literary theory that viewed the evocation of wonder as the main criterion of linguistic beauty.

What questions for future investigation has the project sparked?

I hope this book represents just the first step in mapping out classical Arabic literary theories. I hope it inspires future research that will provide more density to the picture we have: Were there counter trends? When did this aesthetic outlook begin and end exactly? In the book I locate this aesthetic of wonder in post-10th-century Arabic criticism. I argue that there was a major paradigm shift in aesthetic sensibility around the turn of the 11th century from an old school that valued truthfulness and naturalness to—what I call—a “New school of criticism” that was based on wonder. Why this shift happens then is still open to speculation. More can be done to investigate pre-11th-century kernels of this new theory of wonder. On the flipside, I end my investigation in the 14th century. It remains to be seen how late this theory continues to dominate the literary scene. Did it adapt to changes in poetic style in later centuries? Another interesting avenue for investigation that arises from this book is the relationship between this aesthetic theory of wonder and mystical poetics. This is something not addressed by the authors I look at and hence I do not address it in the book. However, there is enough to indicate that some serious connections can be made an aesthetic of wonder and Sufi philosophical concepts. Most exciting to me would be to see whether there are any engagements with an aesthetic of wonder in literatures in contact with Arabic, such as medieval Persian and Hebrew. These are all projects that I hope others will be inspired to pursue.

For me personally, this project has inspired further investigation into the concept of mimesis. In Chapter 2 of the book I discuss how, in the Arabic commentaries on Aristotle’s Poetics, mimesis came to be understood as comparison or simile. I limit my investigation there, however, to the poetic figure of simile. I plan to continue the investigation of this concept in Arabic literature in my second book project and to consider the implications of such a different understanding of mimesis on medieval Arabic conceptions of literary representation generally-speaking, including in prose and narrative.

Why should people read this book?

Arabic Poetics gives the modern reader tools to read and appreciate classical Arabic literature, poetry, and the Quran. The sophistication of Arabic theorizations of aesthetics, which this book exposes, and the universality of their principles makes it important for the study of literary theory in general and literatures beyond Arabic, including modern Western literatures. Anyone interested in understanding how poetry, eloquent speech, and the Quran evoke wonder should read this book.

Learn more about other publications by Princeton University faculty in the humanities by exploring our Faculty Bookshelf.