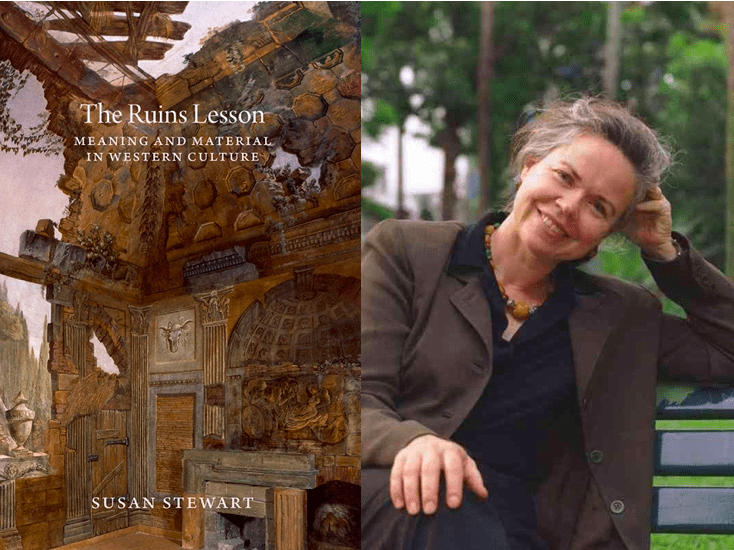

Susan Stewart is the Avalon Foundation University Professor in the Humanities and Professor of English. Her book “The Ruins Lesson: Meaning and Material in Western Culture” was published in January 2020 by University of Chicago Press. This retrospective Q&A is part of an effort to acknowledge all the wonderful books published early in the pandemic.

How did you get the idea for this project?

The central question of my book is: how did ruins–structures that are damaged and moving toward disappearance–become so important in Western art and literature? I knew that many other cultures considered ruins in other ways or not at all: for example, in China natural forms, including decaying or petrified ancient trees, are often objects of contemplation and veneration; in Japan some temples, including the famous Ise Jingu shrine, are disassembled and reassembled every so many decades to preserve the knowledge of how to make them; in Turkey and other places I have visited, restoration practices emphasize renewal rather than the preservation of “age value.” I wanted to get to the heart of why ruins and ruination are sources of aesthetic pleasure in Western European traditions and to think, as I have in much of my earlier work, about the relations between making and unmaking. Underlying my research was (and is) my concern regarding the prevailing economic system’s embrace of “creative destruction” and its disastrous impact upon the environment. Yet a life-time of encounters with actual ruins, from playing in an abandoned farmhouse as a child to teaching for years in Rome and traveling to many ruins sites elsewhere, no doubt also led me to write this book.

How has your project developed or changed throughout the research and writing process?

When I began the project, I knew about late-18th century and Romantic approaches to ruins and I long have had an interest in the ideas and prints of Piranesi. As I continued my studies over many years I gained a much larger perspective on the historical depth of attitudes toward monuments and memorializing. I came to see how first-hand experience of ruins led artists and architects to develop new techniques of representation. From the beginning I had in mind as well the figure of the “ruined person,” particularly the “ruined woman,” and I followed that notion through Hebrew traditions of destroyed cities linked to the chastity of women and Reformation attitudes toward the Virgin, virginity, and practices of iconoclasm. The major periods of ruins interest–Renaissance humanism and Romanticism–came to seem far more continuous than distinct. Today the continuing popularity of ruins images, including those photographic images of urban decay considered “ruins porn,” seems rooted in attitudes that had fully developed by the beginning of the 19th century.

What questions for future investigation has the project sparked?

In the end I began to understand how the living, ephemeral, vegetative forms encircling, penetrating, and breaking down these inanimate mineral structures have contributed to our sense of their beauty and importance. I was glimpsing a return to nature, an integration of human artifacts back into nature. My new work is on the relation of poetry to natural processes–not only as a theme or concern, but also as a responsive practice.

Why should people read this book?

I called my book “the ruins lesson,” but I did not intend the title to sound admonishing or even pedantic. I had in mind the etymology of “lesson” in words signifying to read and to gather. Ruins always compel us to read their shapes and histories and to gather our thoughts, to question the past and to ask ourselves what we might value from the past. No one “should” read my book, but I do hope it welcomes every reader.

Learn more about other recent publications by Princeton University faculty in the Humanities by exploring our Faculty Bookshelf.