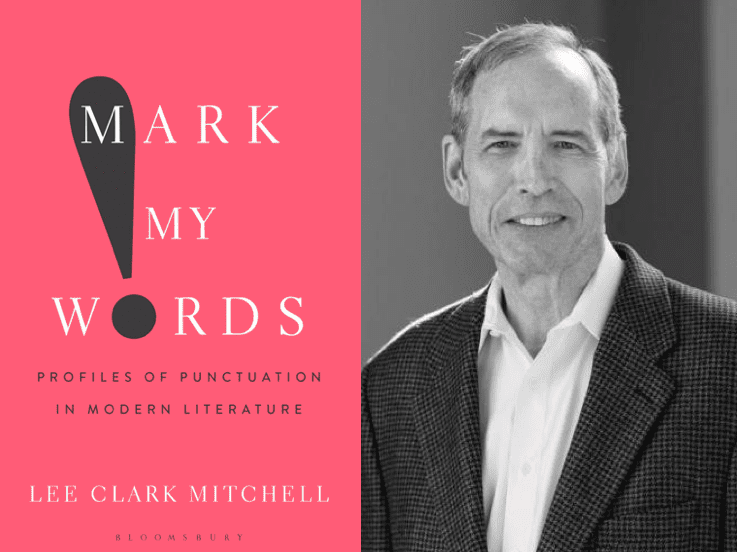

Lee Clark Mitchell is Holmes Professor of Belles-Lettres in the Department of English. His latest book is “Mark My Words: Profiles of Punctuation in Modern Literature,” published by Bloomsbury in May 2020. This retrospective Q&A is part of an effort to acknowledge all the wonderful books published early in the pandemic.

How did you get the idea for this project?

The book started as a slightly whimsical paper for a Santa Fe conference on “Sights and Sites: Vision and Place in American Literature,” where I opened with a hypothetical:

What if one stepped back from the echoing homonyms of this conference—physical sites and ocular sights (or rather, geographical places and symbolic visions)—to consider a map more familiar to most of us: the authorial landscape itself? And rather than gaze outward at cliffs, creeks, and crossroads, why not turn an eye instead to the topographies of punctuation that signal a writer’s signature style?

The paper went well enough, but once I returned home the questions it raised continued to grip me. And I in turn badgered friends, only to be met by an outpouring of ripostes and recommendations, surprising me with the enthusiasm shared for a subject that generally flies under the radar.

How has your project developed or changed throughout the research and writing process?

As it happens, many others are secretly fascinated by the squiggly marks that shape the words we read. And in listening to them, I discovered odd revelations tucked away in W. G. Sebald’s silencing dashes, in José Saramago’s uncorseted syntax, in Nabokov’s imprisoning parentheses, even in E. E. Cummings’s curiously disarming enjambments.

What questions for future investigation has the project sparked?

The psychology underlying a writer’s choice of punctuation continues to intrigue me. Why rely on dashes rather than semicolons, or even than simple commas? Is there something in the about-face of a horizontal line that signals a reversal of grammatical meaning? Or is it the straight lines themselves that attract iconographically, as they did Henry James (known early on as the “dash man”)? (Biographers have even regretted the excision of James’s outmoded underlining of written words for added emphasis, replaced in printed versions with the current style of italicization, since the very “look” of his pages has been silently altered).

Why should people read this book?

I hope, at least for openers, to evoke delight in skewed inquiries into what otherwise seems commonplace, especially on a subject that appears initially pro forma. It’s the kind of subject I associate with my eighth-grade English teacher—who taught me the love of diagramming sentences (and why should I have sequestered her off from her subject with a firm dash instead of a mild comma? Who knows!). But once past the initial delight, I would hope in turn for greater attention to literary style and its pressures, its silent revelations and sneaky emphases.

Learn more about other recent publications by Princeton University faculty in the Humanities by exploring our Faculty Bookshelf.