Watch the colloquium video here.

By Catie Crandell

A colloquium organized in November explored how, in the words of co-organizer Nigel Smith (English), the pandemic has brought “unexpected challenges that have opened up new opportunities” for those who study material texts. The online event “The Virtual Materiality of Texts: Book History during a Pandemic,” attracted 500 registrations from over 24 different countries, according to Smith. The diversity of perspectives and the richness of research and teaching solutions explain the mass appeal of the colloquium.

The first panel, titled “Learning and Teaching through the Screen” brought together Leah Price (Rutgers), Jesse Erickson (University of Delaware), and Tia Blassingame (Scripps College), each of whom described the compelling and creative tactics they have employed to enliven distance learning for courses typically grounded in the handling of material texts.

In a normal semester, Price’s course is designed as a hands-on introduction to fine art printing, teaching students to make paper and practice book binding, while they learn about book history. Forced to pivot with the arrival of the pandemic, Price spoke about “how to teach without touch,” in ways that highlight “low tech, low brow, homespun modes of interaction with the object.” Students applied their knowledge to cheap books that they owned at home, playing a game of 20 questions to identify a book from its material qualities: “Which surfaces are the slipperiest? Which pages are the noisiest? How long could you hold it?” Such questions, the class found, were just as effective as demonstrations of bibliography as a day in special collections might be. Whether a book is “bound for posterity or the trash can,” it can still be a learning tool.

Erickson, who has personally been drawn to “the texture of gold leaf and the musty smell of aged vellum,” acknowledges the feeling shared by many that digital book studies cannot be a substitute for the real thing. Nevertheless, in the context of a society that has generally gone paperless, Erickson argues that “the haptic dimensions of our digital interactions do not disappear. They transform.” Tools such as tour-creation software allow students to explore a digital exhibition or collection space, while enabling students themselves to visually and spatially display the history and materiality of a text. A great work-around in the pandemic, this approach also solves a separate problem–the intimidating nature of the special collections environment. “Virtual reality allows you to visit without having to walk in the door,” said Erickson, “and helps bring students into these spaces comfortably.”

The question of intimidation also featured in Blassingame’s descriptions of her remote book-art courses. For students who don’t come from art backgrounds, the prospect of making an art object, especially one with letterpress technologies, can be daunting. In the remote semester, she noted, “Students were much more able to respond to events happening in the summer and fall because they weren’t forced to use the small edition and letterpress format.” Using printmaking techniques that work just as well with cardboard and tinfoil as they do linoleum or woodblocks, students created artworks that responded to experiences in their daily lives, such as wildfires in California or the stresses of quarantine.

The second panel, “Closed Archives, Open Access,” explored approaches to remote bibliographic research conducted by Nigel Smith (English), Whittney Trettien (U Penn), and Emmanuel Bourbouhakis (Classics).

Smith’s talk mapped the convoluted and thrilling process by which a previously unknown manuscript was uncovered in a newly digitized collection from a library in Kassel, Germany. Scholars first took notice of the collection in 2010, when it was discovered to include the first-ever translation in another language of Milton’s Paradise Lost, which had appeared in German shortly after the poem’s publication in 1667. The great surprise came, Smith explains, with the discovery of a completely unknown document in the collection, which was written in English by an Englishman named Thomas Tillum. “This tract is a hot potato because it is the only English defense of divorce apart from Milton’s,” Smith explained. Tillum’s treatise, which Smith sums up as a “full-scale call for polygamy,” compares marriage outside the faith to something akin to the “experience of the Spanish Inquisition.” Even though this manuscript discovery was profoundly enabled by digitization, Smith maintains that “the only way to understand these archives would be to visit them.”

Unlike Smith, who stumbled across a new text because of digitization, Trettien was forced to dig into an archive of texts that had been digitized before the pandemic, which “completely trashed” her summer research plans. Trettien found herself returning to images of documents produced by a religious household called “Little Gidding,” which had flourished in the 1630s. Her focus was a series of books made by the women of the Collet family that “harmonized” the four gospels in a single text. Forced to rely on materials that were already at hand, Trettien collaborated with one of her students, Zoe Braccia, to create the first online edition of Susanna Collet’s harmony, which was in part a commonplace book that organized sentences around the emotions. Using Digital Mapa, a tool developed for annotating maps, the pair annotated the text and were able to eventually reconstruct Collet’s library from the fragments of ‘learned authors.’

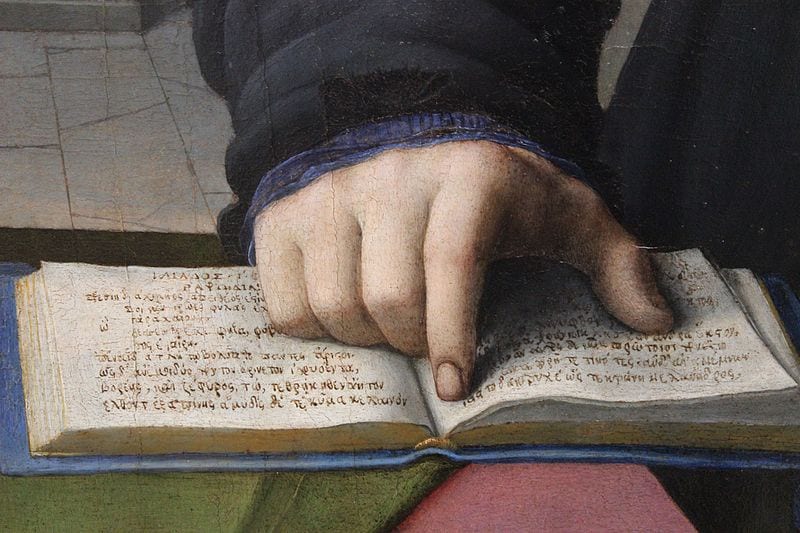

The final talk, presented by Bourbouhakis, addressed the relative scarcity of digitized byzantine manuscripts in relation to paleography, or the study of ancient writing systems. As Bourbouhakis attests, “The study of manuscripts has been defined by the very limited number of books available,” and that, in fact, “nearly every scholar of a particular age has some story to tell of intrepidness, or even outright extortion, in order to see a manuscript and make or procure an image of it.” As a result, most paleographical research is centered around great libraries like the Bodleian at Oxford or the Vatican libraries, so that the field has essentially subsisted on questions based in a pre-digital library. For paleography, perhaps more than in any other field, the power of the digital image might prove to be a major game changer, and one that can “reconstitute paleography as a mode of intellectual history.”

The colloquium was co-organized by Jin-Woo Choi (History), Anthony Grafton (History), Leah Price (Rutgers), Nigel Smith (English), and Anna Speyart van Woerden (History), and sponsored by Committee for the Study of Books and Media, the Committee on Renaissance and Early Modern Studies, and the Rutgers Initiative for the Book.