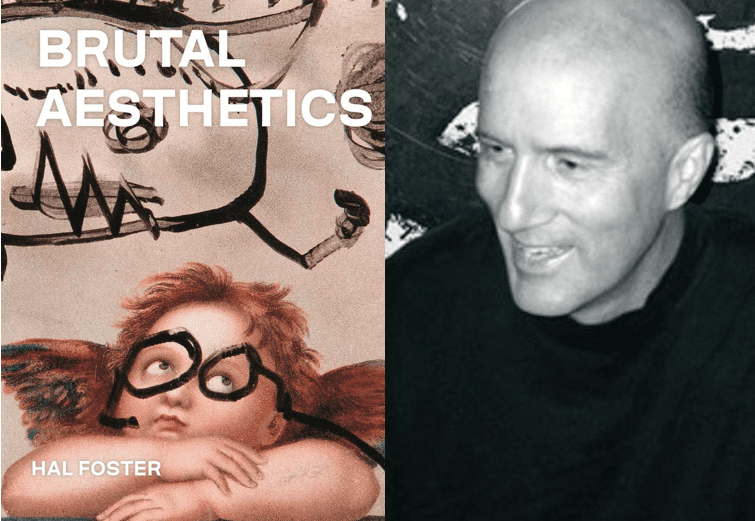

Hal Foster is the Townsend Martin, Class of 1917 Professor of Art and Archaeology. His latest book “Brutal Aesthetics: Dubuffet, Bataille, Jorn, Paolozzi, Oldenburg” is published by Princeton University Press.

How did you get the idea for this project?

The book was born of my puzzling over a paradoxical statement from Walter Benjamin: modernism teaches us “how to survive civilization if need be.” Although he varies the phrase in a few texts of the early 1930s, he never explains it. Given the situation in Europe, the referent of “civilization” seems clear enough; it is the travesty of civilization authored by Fascism and Nazism, civilization turned into its opposite. This is the barbarism that Benjamin hopes, in a desperate dialectic, to reverse. “Barbarism? Yes, indeed. We say this in order to introduce a new, positive concept of barbarism. For what does poverty of experience do for the barbarian? It forces him to start from scratch; to make a new start; to make a little go a long way…” For me this opened up a different way to think about modernism, especially after World War II, and it led me to the five artists and writers I take up.

How has your project developed or changed throughout the research and writing process?

I didn’t expect the issue of sovereignty to be so persistent. Maybe this shouldn’t have surprised me; after all my subjects operated not only in the ruins of a world war but also in the vise between Soviet totalitarianism to the East and American triumphalism to the West. This was an overdetermined situation—an old liberal order destroyed by Nazi and Fascist regimes, these regimes overcome in turn but at immense cost, and then a treacherous Cold War locked in place—and it had to prompt questions about the nature of political authority. On the one hand, this produced a great uncertainty about the ground of lawful rule; on the other, it incited a concomitant interest in figures that might count as outsiders or outlaws to such authority. How to create, how to survive, in a state of emergency?

What questions for future investigation has the project sparked?

Modernist scholars have often cast prewar avant-gardes as transgressive, in a position of radical innovation, and postmodernist critics have often positioned postwar avant-gardes as resistant, in a position of stern refusal to the status quo. In both cases the avant-garde assumes an oppressive presence of law, whether that is understood as social convention or political rule or both, as the object of its contestation. But what if no such ground exists in this stable form? Again, one response is to seek out a place before or outside a presumed order from which to begin again. Another is to trace the fractures that persist within it, to pressure them, even to activate them somehow. I want to look into both kinds of practices in future work.

Why should people read this book?

It’s a primer on how to survive civilization, or at least on how one generation of artists and writers approached that problem. Who wouldn’t want that in their go bag?

Hal Foster will be joined by fellow art historian Yve-Alain Bois (Institute for Advanced Study) for a livestream discussion of his new book, hosted by Labyrinth Books on December 2, 2020.

Learn more about other recent publications by Princeton University faculty in the Humanities by exploring our Faculty Bookshelf.