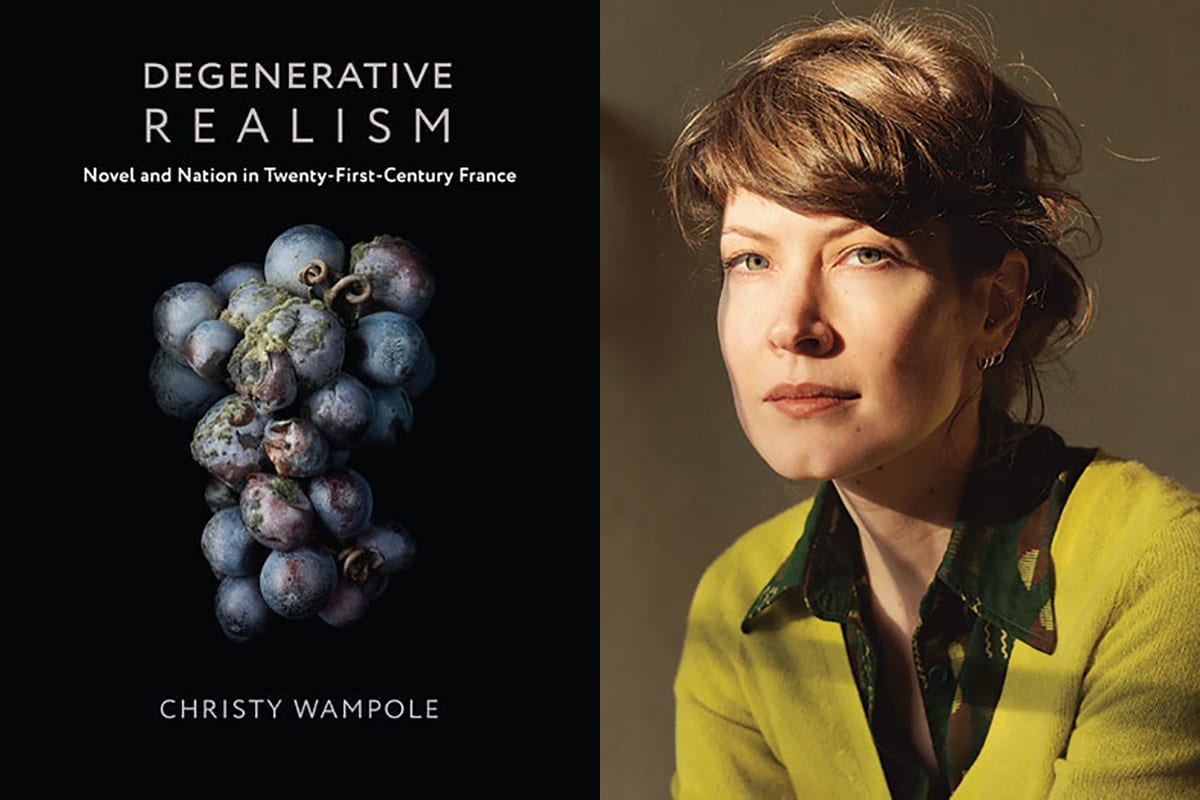

Christy Wampole is Associate Professor in the Department of French and Italian. Her latest book is Degenerative Realism: Novel and Nation in Twenty-First-Century France, published by Columbia University Press.

How did you get the idea for this project?

As I was writing my last book Rootedness: The Ramifications of a Metaphor (2016), I was struck by how frequently organic metaphors are applied to cultural phenomena. Culture seems to sprout or be birthed, then it matures and finally becomes infirm, dies, and decomposes. In reading contemporary French fiction, I noticed that many authors were applying metaphors of degeneration and decay to French society or more broadly to Western civilization. The pattern was too pervasive and consistent to ignore. I wondered why so many French novelists have turned a sociological gaze on themselves and their communities and why the most apt concept they found to describe what they observed was degeneration. The more curious thing about these books is that in them, not only is France depicted as a moribund entity but reality itself also breaks down throughout the novels’ pages. The form degenerates in synchrony with the content.

How has your project developed or changed throughout the research and writing process?

At the beginning, I planned mainly to write about degenerative realism as a new phase in the long realist tradition of the French novel. The project was going to be purely literary. But I quickly realized that because these books include heavy political and sociological elements, I’d have to expand the project’s scope. Degenerative Realism approaches the problem through a number of fields: the social sciences, particularly demography, journalism, political theory, and even information science. I never would have guessed at the beginning of the project that I’d dedicate a whole chapter to the history of the Minitel, a kind of proto-Internet developed and funded by the French state, and the impact of the internet and social media on the degeneration of reality described by the novels in my corpus. I learned a great deal about everything from ideological fiction and the history of the far right in France to the strategies contemporary authors use to address France’s historical traumas and its current turbulence.

What questions for future investigation has the project sparked?

I suggest in the introduction that, while my book deals only with French literature, there are almost certainly other contemporary literatures that deploy degenerative realism as a means to explore the political and social turmoil of today through fiction. For example, I wouldn’t be surprised if the pattern exists — perhaps in a slightly different iteration — in some contemporary American novels, or German or Italian ones. I’d expect to find some version of it throughout Europe and perhaps throughout North and South America. My hope is that literary scholars in other fields will find the concept useful in their own research. Because some of the factors that have contributed to the development of degenerative realism exist beyond France’s borders — the arrival of the internet, the destructive effects of globalization and capitalism, the breakdown of orientation points like family, faith, and tradition — I am certain that novelists in other places have changed the way they depict reality in response to these same factors. I am curious to know how widely the term applies.

Why should people read this book?

I think panoramically when I write. This is true of Degenerative Realism, which starts with an analysis of conspicuous patterns in some contemporary French realist novels and then poses the question, “Why this and why now?” In other words, my book is not just about the French novel. It is about French society writ large. People should read it because it shows how to read panoramically. It shows how a cultural artifact like the novel can offer a psychogram of the society that produced it. It is tempting these days to specialize, to focus on a small object and know it intimately but never look up at its wider context to understand which conditions generated it. I tried to model the kind of reading that I wish was more common. Hopefully some scholars will be inspired by Degenerative Realism and will apply that kind of panoramic reading and thinking to their own projects.

Learn more about other recent publications by Princeton University faculty in the Humanities by exploring our Faculty Bookshelf.