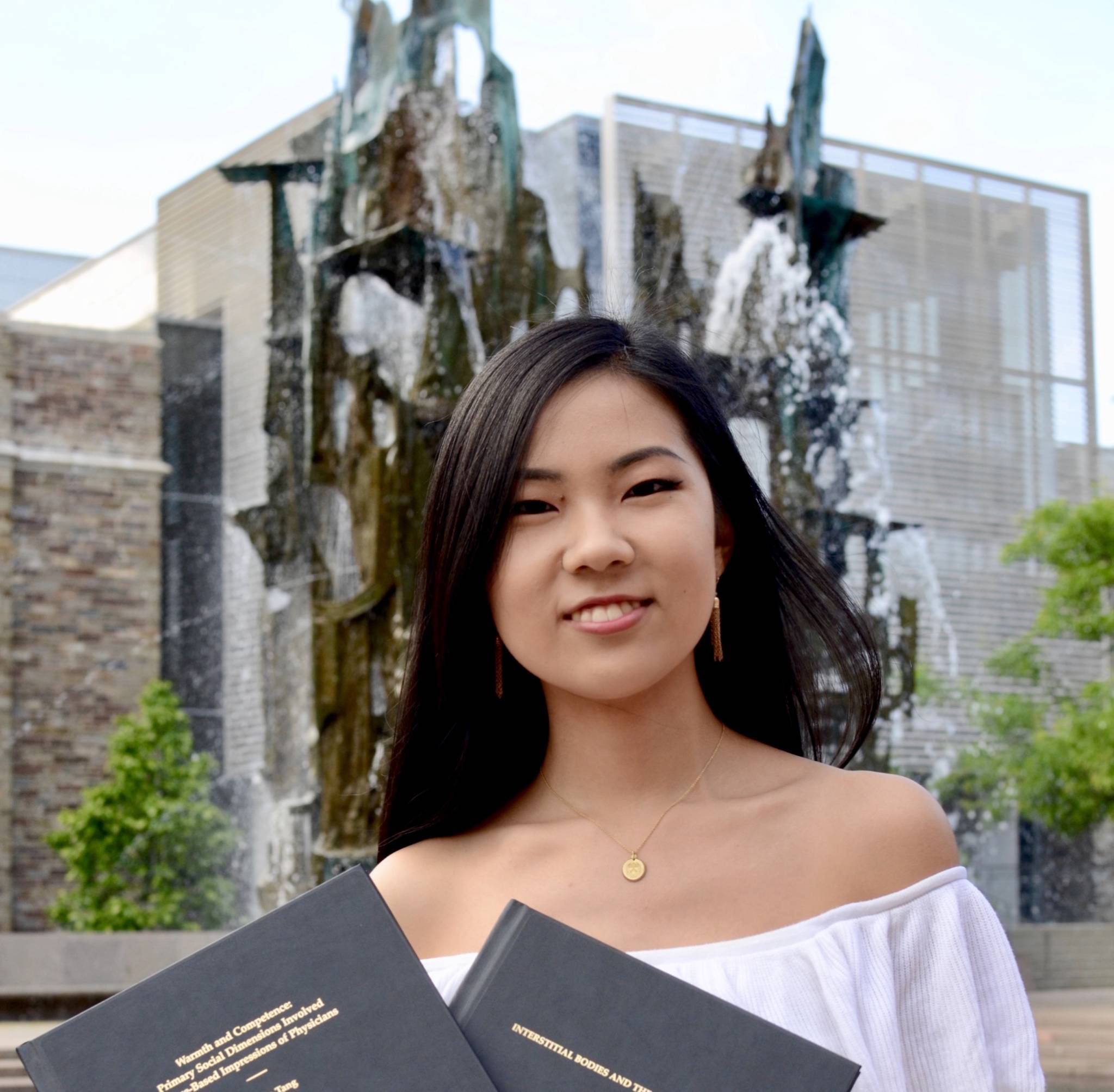

Originally from Perth Amboy, NJ, Victoria Tang ’19 graduated with a degree in Psychology as well as certificates in Neuroscience and Humanistic Studies.

Having participated in Interdisciplinary Approaches to Western Culture (“HUM Sequence”) as a freshman and the HUM trip to Greece as a sophomore, Tang explored an interest in the medical humanities through the HUM certificate, taking advantages of classes across multiple departments and working as a research assistant for the Bodies of Knowledge working group. Her senior thesis in psychology, advised by Alexander Todorov (Psychology), examined social dimensions involved in face-based judgments of physicians, focusing on the relationship between perceptions of warmth and competence and its potential implications for telemedicine. Victoria also completed a senior independent project for the HUM certificate, advised by Elena Fratto (Slavic Languages and Literatures), on the anatomical gaze and the specimenization of human bodies.

On campus, Victoria was involved with the Pace Center for Civic Engagement as co-chair of the executive board of Community House and co-founder of Generation Speak, a Community House project that emphasizes storytelling as a means of building community among local youth, students, and seniors. Victoria was also chair of the Princeton Internships in Civic Service (PICS) Student Advisory Council and a member of the club sailing team. Next year, Victoria will be working at the YK Pao School in Songjiang, China as a 2019-2020 Princeton in Asia (PiA) fellow before returning to the United States for graduate school.

You were a psychology major and also completed a certificate in neuroscience. What interested you in the HUM Sequence?

I went to an engineering-focused magnet high school, and while I greatly appreciated the skills I learned there, I came to Princeton knowing that I wanted to take advantage of the incredible humanities education here by pursuing something interdisciplinary. The HUM Sequence seemed like a fantastic opportunity to immerse myself in that world by building a broad foundation of knowledge, meeting students with a similar sense of curiosity, and challenging myself.

As I gradually defined my interests in psychology and neuroscience after freshman year, the HUM certificate continued to be a way in which I could both supplement and complement my “core” courses. For example, after taking SLA/HUM368 Literature and Medicine, I became involved in the medical humanities, which combined all of my interests through discussions ranging from neurodiversity to the relationship between horror and anatomy. I also had a lot of fun in bringing together my psych and neuro classes with my humanities ones – such as by taking PSY411 Psychology of Face Perception, where we discussed the neural basis of face perception and statistical errors in algorithm use, alongside ENG319 About Faces, where we thought about philosophical and aesthetic theories of the face and explored the collections at the Princeton University Art Museum; or, another semester, thinking about synesthesia in both SLA417 Vladimir Nabokov and PSY/NEU345 Sensation and Perception.

Were there any pivotal moments during the course which shifted the way you approached your learning?

Do they still ask for your favorite word on the Princeton application? My choice was between “intricacies” and “magnitude,” and I remember the first time I read a text and felt like I was finally getting closer to grasping both: its expansive implications and place in context, and at the same time, the complex internal structure and details that gave it such impact. It felt like everything I’d been learning in lectures, precepts, and each painfully slow paper-writing process was coming together, and beyond the sense that I’d learned something myself, I was finally gaining confidence in talking about my thoughts. That may be a small accomplishment, but it opened up the way I approached my learning – that sense of discovery pushed me to keep seeking out more information on my own, to do so with earnest enthusiasm, and to communicate more openly with others.

Why did you become a student mentor and what did you like about it?

It may sound cliché, but one of the best parts of having participated in the HUM Sequence has been the community and the friendships (much love to AW ’19, EM ’19, and IA ’20!). People are so passionate, so driven, and so intensely curious about so many things, and being in that environment was central to my own growth as a student and scholar – I wanted to consolidate what I’d learned and contribute in the same way to future cohorts of HUM students.

Having come into HUM without a strong humanities background, and having struggled with so many insecurities as I learned to do close reading, write papers, and engage in precept, I wanted to support students coming from similar situations.

What role do and should the humanities play in the lives of students today? What do you think that HUM/the humanities can offer students in the sciences?

I think almost every HUM student is familiar with these questions, which often come with the implied (or explicit) “Why are you studying this? What value does this add to your degree?” Even the first few days of the HUM Sequence teach so many of the core skills that we come to college to learn: how to listen, observe, and analyze; how to evaluate arguments in context and craft our own; even something as seemingly simple as how to speak up and add our own thoughts in precept or in office hours. That, for me, was actually one of the most valuable lessons I learned from HUM. Recognizing that even as (over)enthusiastic, naïve freshmen in college, we could add our thoughts to a humanistic tradition thousands of years old, and that these contributions were not only valid but also valuable – that’s a pretty incredible realization, and it carries over to so many other aspects of our lives as students. It helps teach us that being a student involves learning and contributing, and that both inside and outside of the classroom, we belong to this vast history of people thinking, feeling, creating, and exploring.

HUM has also changed how I think about being a student “in the humanities” or “in the sciences.” My readings for a neurobiology seminar may still be very different from those in, say, a Slavic literature class, but the strategies for approaching one can absolutely inform the other, and learning to make those connections has been one of the most important skills I’ve gained at Princeton. Contrary to what I used to think, working across both the humanities and the sciences isn’t about compromise – it’s about finding the many areas where they overlap, and understanding the opportunities that that richness of thought offers. The HUM program has been particularly great for this, and I appreciate how interdisciplinary and vibrant the community is. It’s given so much more depth and meaning to what I’ve learned, and continually pushed my sense of curiosity and wonder at how much more there is out there.

I’m not sure that I can even begin to adequately describe how the humanities enhance our lives as students, or list all the things they can offer the sciences, or put the value of a humanities education into words. If nothing else, however, through HUM I’ve met people who can answer those questions far more articulately and profoundly than I ever could, and that is absolutely part of its value as well.

Why did you choose to pursue independent work in the humanities, and what influence did the HUM program have in shaping your research interests?

I first became interested in the medical humanities when taking SLA/HUM368 Literature and Medicine, and then became involved as a research assistant with the Bodies of Knowledge working group, which engaged with questions around illness, health, and the body from interdisciplinary viewpoints both within and beyond the humanities. My senior independent work came from research I did in HUM/SLA/EAS597 Authorship of the Body: Health, Illness, and Medicine in Global Perspective with Professor Amy Borovoy (Anthropology) and Professor Elena Fratto (Slavic). I had never taken a graduate seminar before, but after getting over the initial sense of intimidation, I was awed by the diversity of expertise and experience that my classmates brought to each conversation and wanted to try doing my own serious research.

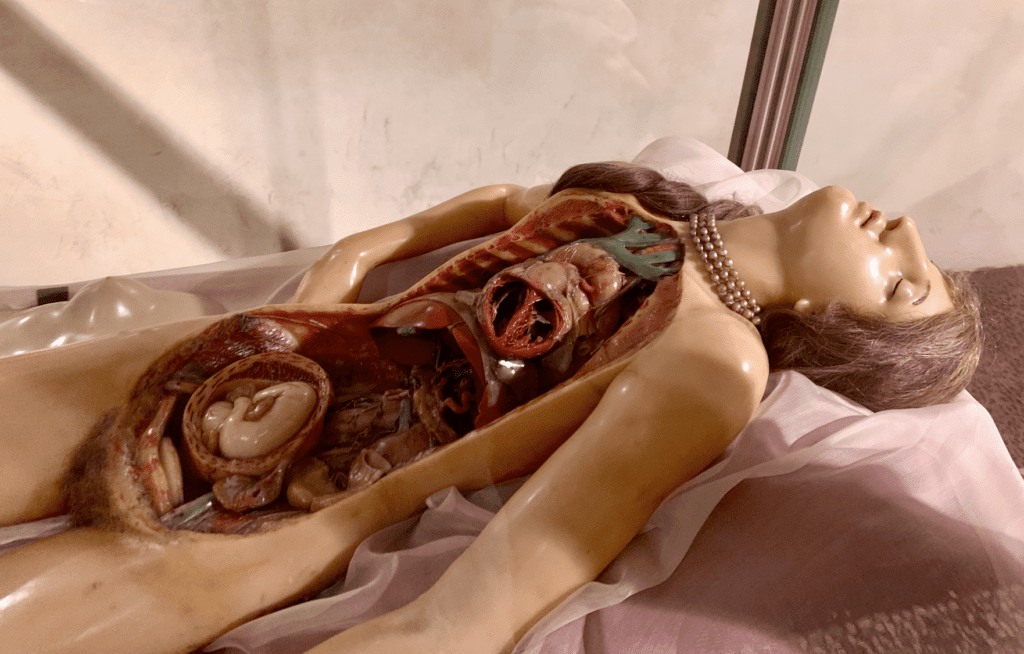

For my final project in that class, I wrote on the Mütter Museum’s Hyrtl skull collection and the balance between individuation and objectification in the display of human remains, which led me to the questions of specimenization, the anatomical gaze, and the body that I explored in my HUM “thesis.” Specifically, I was interested in what could be called “interstitial” bodies – specimens that exist somewhere between what we might consider fully “authentic” (such as a human skeleton) and fully “artificial” (such as a plastic model of a heart) – and how the processes of transformation involved in creating these bodies reflect various ideas of anatomy, authenticity, and humanity. The HUM program generously funded research in London, Florence, and Bologna to study some examples in person, and I was lucky enough to see the 18th century wax anatomical models that include the “Anatomical Venuses,” as well as the plastinated cadavers of the Body Worlds exhibits.

I am so grateful to the HUM program for having been continually supportive of my exploration in the humanities, from the moment Dr. Crown personally responded to my pre-freshman-year email about the Sequence all the way to our Class Day reception in Joseph Henry House. For all of the ways in which HUM has shaped my intellectual interests, it’s been the kindness, attentiveness, and encouragement of the staff and faculty that’s been most valuable to me and given me the confidence to pursue this work.

What are your plans after Princeton and did HUM have any impact on your decisions?

This August, I will be moving to Songjiang, China to begin a fellowship with Princeton in Asia (PiA) at the YK Pao School, a bilingual boarding high school that emphasizes “whole-person” education through co-curriculars, cultural programs, and international experience. As a Fellow in the Student Life Office, I’ll be working with the international exchange program, guiding students through the U.S. college application and essay-writing process, and supporting co-curricular programs. I’m excited to serve in a role that ties together my interests in civic service, mentorship, interdisciplinary education, and international exchange, and I know that I’ll be bringing lessons I learned in HUM with me (along with a couple of my favorite readings!).

HUM certainly contributed to my passion for interdisciplinary education and my interest in mentorship. It also inspired (and made possible) many of the international experiences I had at Princeton, such as the HUM trip to Greece and a summer program in Florence through NYU Gallatin, which led me to choose an international fellowship after graduation. After I return to the United States, I hope to further build on my education in the humanities in graduate school: my interest in the medical humanities has led me to consider a master’s in public health, and I hope to be able to combine those studies with further work in the history of science, medical humanities, and other interdisciplinary areas.