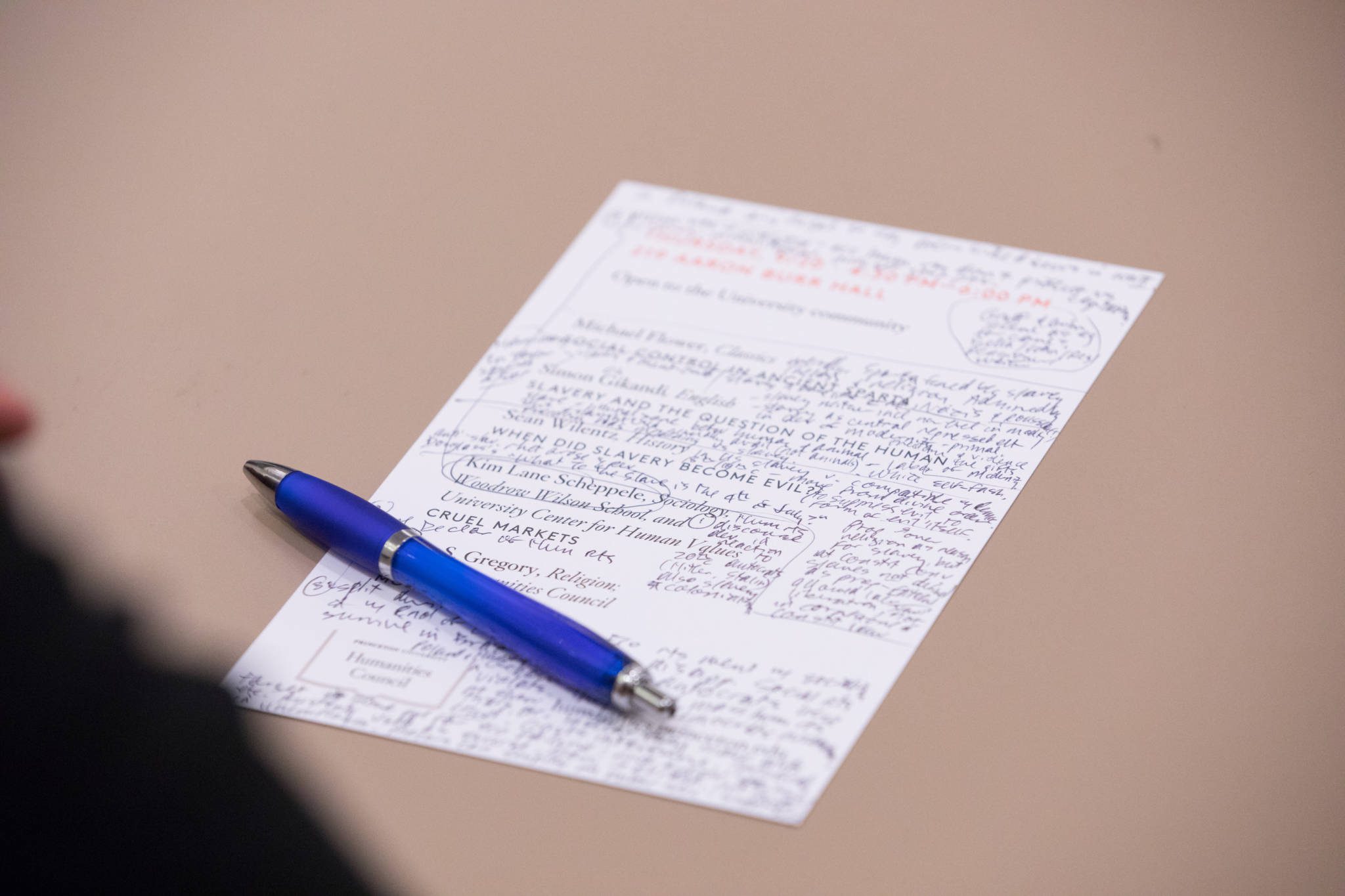

To launch each academic year, the Humanities Council invites the University community to reflect on a theme spanning the humanities. “Capturing the Human” formed the focus of the 12th Annual Colloquium on Thursday, September 20 in 219 Aaron Burr Hall.

“Captivity, bondage, and incarceration have long elicited both scholarly inquiry and activism from humanists,” Eric S. Gregory, Chair of the Humanities Council and Professor of Religion, said. “What might ‘capturing the human’ mean in our teaching and our research today, for the narratives we tell, the methods we adopt, the discipline we seek, and the dilemmas of representation in our work?”

Classics Professor Michael Flower noted that of the ancient Greek city-states, Sparta most controlled the lives of citizens. Yet it lasted generations longer than twentieth-century totalitarian governments did.

He attributed Sparta’s success partly, and perhaps most importantly, to its religion. Spartan male citizens participated in religious festivals, which legitimated the regime while inculcating certain values and ideals, as often as they trained for war. However, modern academics have largely focused on nonreligious factors.

“This oversight by scholars may result from a failure to take ancient Greek polytheism seriously as a coherent system of ritual practices and sincerely held beliefs with its own intrinsic rationality,” Flower said.

English Professor Simon Gikandi described enslavement, which includes cultural deracination, social death, unpaid labor, and violence, as a repressed mark of modernity. The new global narrative of freedom masks how black suffering enabled white self-fashioning.

“Slavery is one of the literal dirty secrets of modernity,” Gikandi noted. “Modernity came into being through acts of violence, acts directed at the bodies of those who are considered to be outsiders.”

On the other hand, a not-so-dirty secret of modernity is anti-slavery, History Professor Sean Wilentz said. He explained that in the remarkably short period from the mid-seventeenth to the late-eighteenth century, traditional rationalization for slavery crumbled, yielding to sensibilities identifying with the enslaved.

“The history of the modern West, and especially the history of what has become the United States, has flowed from this fundamental rupture — not the endurance of slavery, but the rendering of slavery as evil,” Wilentz noted. “Modernity has included the struggle to alleviate, overcome, and finally abolish sadistic oppression, above all the institution of property in human beings.”

He dated American anti-slavery back to the Revolution. On the eve of the Battles of Lexington and Concord, a group began organizing the first ever anti-slavery political society, later known as the Pennsylvania Abolitionist Society. Eventually, the effort birthed the world’s first mass anti-slavery political party, the Republican Party of Abraham Lincoln.

Kim Lane Scheppele, Professor of Sociology and International Affairs in the Woodrow Wilson School and The University Center for Human Values, said the modern understanding of human rights emerged after World War II. The international response addressed particular tactics, especially from the twentieth century, as well as the legacy of slavery, while slightly anticipating de-colonialization.

“The current state of human rights is only a set of protections against the kinds of abuses that were common in past authoritarian episodes. But we haven’t yet gotten ahead of the new autocrats,” she said.

Scheppele defined the new autocrats as those who, once elected by one constitutional democracy after another around the world, remove checks on power and substitute majority rights for minority rights. They undermine civil and political liberties by manipulating free markets. Examples include firing dissidents, having businesses bought in what look like voluntary transactions, and depriving enemies of domestic job opportunities so that they must emigrate. These offenses should count as violations of human rights too, Scheppele argued.

The Colloquium panel speakers are recently appointed Old Dominion Research Professors who will engage in the intellectual life of the Council and serve as Faculty Fellows in the Society of Fellows in the Liberal Arts for the academic year 2018-19.

Watch the full discussion here.

By Ruby Shao ’17