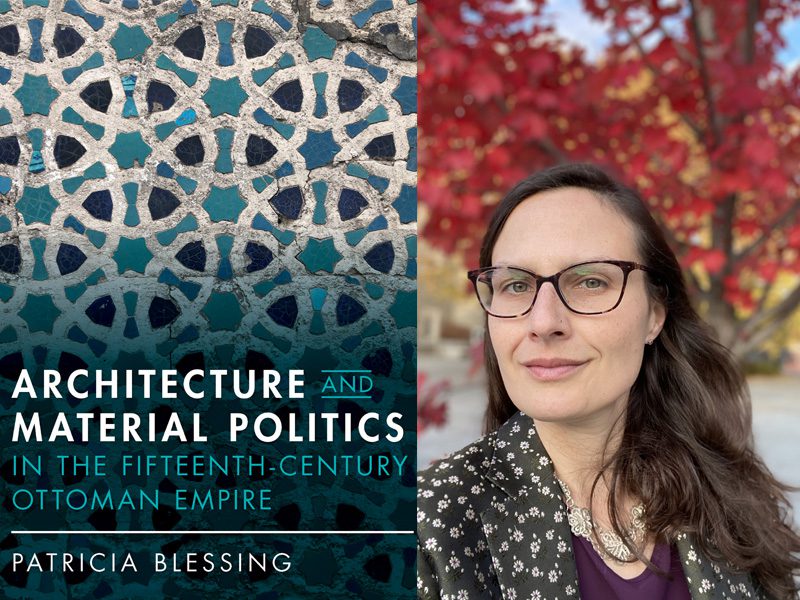

Patricia Blessing is Assistant Professor of Art and Archaeology. Her book “Architecture and Material Politics in the Fifteenth-century Ottoman Empire” was released in November 2022 by Cambridge University Press.

How did you get the idea for this project?

The project emerged from the epilogue of my first book, “Rebuilding Anatolia after the Mongol Conquest: Islamic Architecture in the Lands of Rūm, 1240-1330 (2014),” which was based on my dissertation. There, I reflected very briefly on continuities and ruptures between the period of Mongol presence in the region that I had worked on, and early Ottoman architecture. A visit to Bursa, the first Ottoman capital and a major site of patronage for centuries, had sparked my interest in understanding ties to earlier monuments in the same region, and beyond. Despite often separate historiographies, there is chronological overlap as the Ottomans first emerged as local rulers in northwestern Anatolia in the late thirteenth century, and the earliest extant monuments built under their patronage date to the 1330s, the same period that I had been studying for cities further to the east. From there, I eventually developed my project on Ottoman architecture in the fifteenth century although I did take a detour writing on medieval monuments in Spain for a few years. That body of work also allowed me to develop research in sensory art history, on which I draw in my new book, and also in the project I am working on now.

How has your project developed or changed throughout the research and writing process?

I started out with a plan to work on the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, to understand the first century or so of Ottoman architecture. The more I read, the more I realized that this period is quite well understood, due to the wonderful work of scholars like Suna Çağaptay, Oya Pancaroğlu, and Robert Ousterhout. I also detected a gap in the literature on Ottoman architecture, in that not a whole lot was available for the period between c. 1380 and 1453. That latter date of course marks the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople, the end of the Byzantine Empire, and the beginning of the transformation of this city into the Ottoman capital. Çiğdem Kafescioğlu studied that process in her book Constantinopolis/Istanbul (2009). As I continued my research, I realized that I did not want to treat 1453 as a breaking point – it was one, in many ways, but there was also much continuity beyond that date in Ottoman architecture. Eventually, I ended up writing on the long fifteenth century, drawing on examples dating from the 1380s to the 1510s, getting into the early modern period as well.

What questions for future investigation has the project sparked?

As I was writing my book, I became more and more interested in questions of design, and in the use of paper as a vehicle for it. I explored part of these questions in my book, as I examined how elusive (in the sense that they haven’t been preserved) paper templates could have played a role in how monuments and architectural decoration from stone to tile and woodwork were created. Such templates could also have traveled between sites along with the highly mobile makers who produced them, even though we lack physical evidence. I also kept running into the fact that interior decoration is often only partially preserved, and that even buildings that retain their original function, such as mosques, are filled with modern objects rather than historical ones. The latter are of course in museum collections, sometimes in their place of origin my more often dispersed around the world due to looting to supply the art market since the 19th century. Right now, I am working on a project in which I want to address two central questions: first, how interiors were designed and second, what we can understand of the relationship between buildings and the objects that furnished them. As I write this, I am in Istanbul for a semester of research, so my ideas are still very much forming, but I have been able to work on objects that are connected to specific, extant buildings, and will be part of my next book.

Why should people read this book?

The book is an architectural history of an empire that during the time covered spanned from the Balkans to southeastern Anatolia, and the border region between today’s Turkey and Syria. So the book offers insights into the architectural heritage of a wide geography, even though it is by no means a catalog of all monuments that have been preserved, let alone ones that did not survive to the present. Readers who are familiar with Ottoman architecture of the sixteenth century, such as several major mosques in Istanbul and Edirne, may be interested in the pre-history of that moment, when the Ottoman “star architect” Sinan took center stage. The book also looks at transregional connections to cities such as Venice, Cairo, Damascus, Samarqand, and Tabriz, cultural centers of the time that are also studied by scholars who work in intellectual history, political economy, and literature.

Learn more about other publications by Princeton University faculty in the humanities by exploring our Faculty Bookshelf.