By Jon Garaffa ’20, Humanities Council

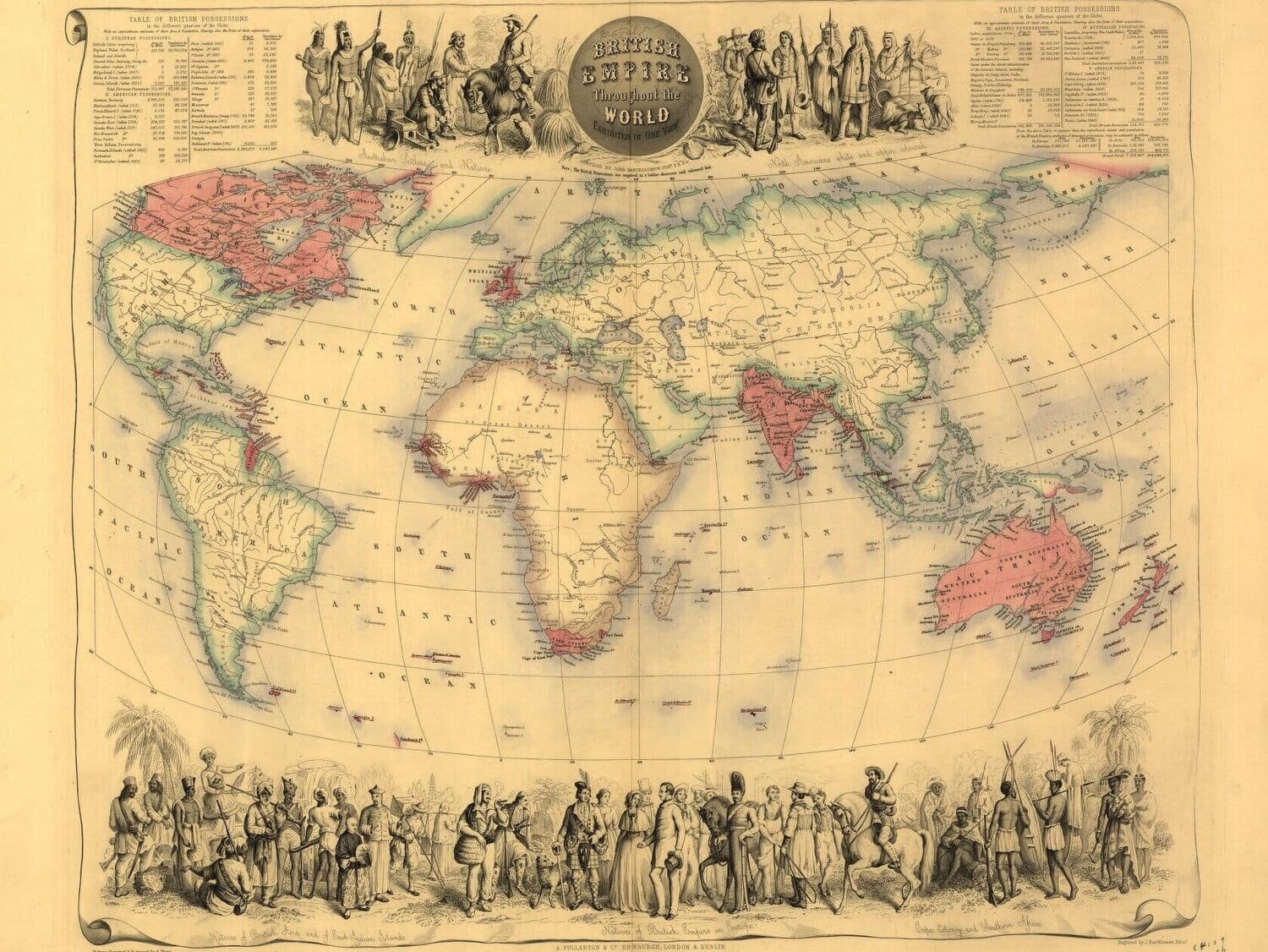

How have art and medicine shaped historical perceptions of minorities? Helping answer such questions, a Rapid Response Magic Grant of the Humanities Council has funded student researchers, image permissions, and further development of an existing website for the project “Pathologies of Difference: Mapping the Art of Colonial Medicine.” This digital resource examines how the interplay among doctors, pictures, and race in the British Empire spawned medical racism that still influences healthcare, even beyond the United Kingdom, today.

In the summer, Anna Arabindan-Kesson (African American Studies, Art and Archaeology) started “Pathologies in Difference” as a series of webpages to add to her personal website. She developed it in collaboration with research assistants Jessica Womack GS, Phoebe Warren ’21, Bhavani Srinivas ’21, and Sydnae Taylor ’23.

The initiative evolved from Arabindan-Kesson’s Spring 2020 freshman seminar, FRS 120: “Pathologies of Difference: Art, Race and Medicine in the British Empire.” The class focused on how racial injustice, slavery, and colonialism highly influenced the construction of medical knowledge, as well as how medicine shaped conceptions of race.

In teaching the seminar, Arabindan-Kesson realized that the largely visual domains of art, medicine, and perceptions of race rarely receive consideration together, leaving a niche for her to investigate. Thus, project development started in Summer 2020 as a continuation of these course themes, and the database went live on her website in Fall 2020. Arabindan-Kesson also saw the course and project as ways of connecting art history with her own medical background. She worked as a Registered Nurse in the UK before completing her doctorate in African American Studies and Art History at Yale University.

“We are looking at examples of meanings about contagion and quarantine—how some of these discourses around geography and contagion came to be understood, along with how meanings about race came to influence the ways Black and white people were viewed by doctors, and treated differently,” explained Arabindan-Kesson.

According to its landing page, “Pathologies of Difference” seeks to shed light on the ongoing global pandemic. Responses to COVID-19 have highlighted healthcare injustices borne of longstanding, geographically distant histories of slavery and scientific racism.

“Though the project is situated in the British Empire, we are having to think about colonialism much more broadly,” Womack said. “As a culture, in order to grasp what people of color are going through right now in regards to COVID-19, we really have to think about the last two or three centuries, and how this has culminated in a healthcare system that does not attend equitably to all people in the U.S.”

Medicine formed an integral part of colonialism, with medical racism manifesting in the ways British doctors experimented on enslaved populations. Notably, British physician John Quier inoculated a population of 850 enslaved people in Jamaica with smallpox to test its effects. False beliefs circulated due to white supremacy and efforts to pseudo-scientifically justify racism, explained Womack. Later, artwork in the U.S. continued to depict people of color to their detriment. For example, a pamphlet by U.S. physician J. H. Van Evrie compared drawings of Black and white faces, portraying Black people as inferior. Additionally, U.S. doctors continued to experiment on Black enslaved people without their consent in order to invent new medical treatments and practices.

Arabindan-Kesson noted that COVID-19 has posed practical and logistical challenges for the project. The pandemic impeded the hands-on work required by the latter half of the course, when the seminar students originally planned to visit archives in London. Now that the course has finished, the project research assistants continue to work back in their homes, separate from one another and from many of the physical archives, collections, or objects that may help them.

Still, the researchers want to provide as authentic of an educational resource as possible amidst the circumstances. They must somehow present the project in a digital medium, telling the stories behind the images and objects without the physical collections themselves. Finally, the team members must coordinate with one another extensively, considering time zone differences when arranging meetings.

The project team has also created an Instagram page that contains educational images and captions describing the relationship between slavery and medical knowledge. For instance, one post contains a map from 1850 showing crossovers of art, medicine, and race in the British Empire and the United States. Others document experimental or artistic attempts to create a typology of racial difference, such as through the pseudoscience of phrenology, which claimed that the measurement of bumps on the skull could predict personality traits. Accompanying drawings fueled racist stereotypes.

“We are hoping that this will become a database for students and academics, to help them to direct their research,” said Arabindan-Kesson. She observed that scholars have understudied the many connections among art, medicine and race in terms of empire. “Pathologies of Difference” will strive to reveal how these histories interact and influence the ways in which we care for one another.