By graduate students Brian Wright, Poorvi Bellur, Kate Carpenter, Kim Worthington, and Mateusz Falkowski

Old journals harbor many mysteries. Such puzzles might range from simple illegible scribbles to far more complicated head-scratchers, each in their own way demanding the archivist’s eye and the historian’s instinct to decipher. In these trying times, with research access widely curtailed or restricted, the Public Transcriptions Project, a Rapid Response Magic Project of the Princeton University Humanities Council, set out to turn some of the Princeton University Library’s nineteenth-century manuscripts into searchable digital articles for the growing online database of Special Collections. Historical research, especially these days, depends on reliable access to archival material. The Public Transcriptions Project seeks to make such material as accessible, readable, and user-friendly as possible.

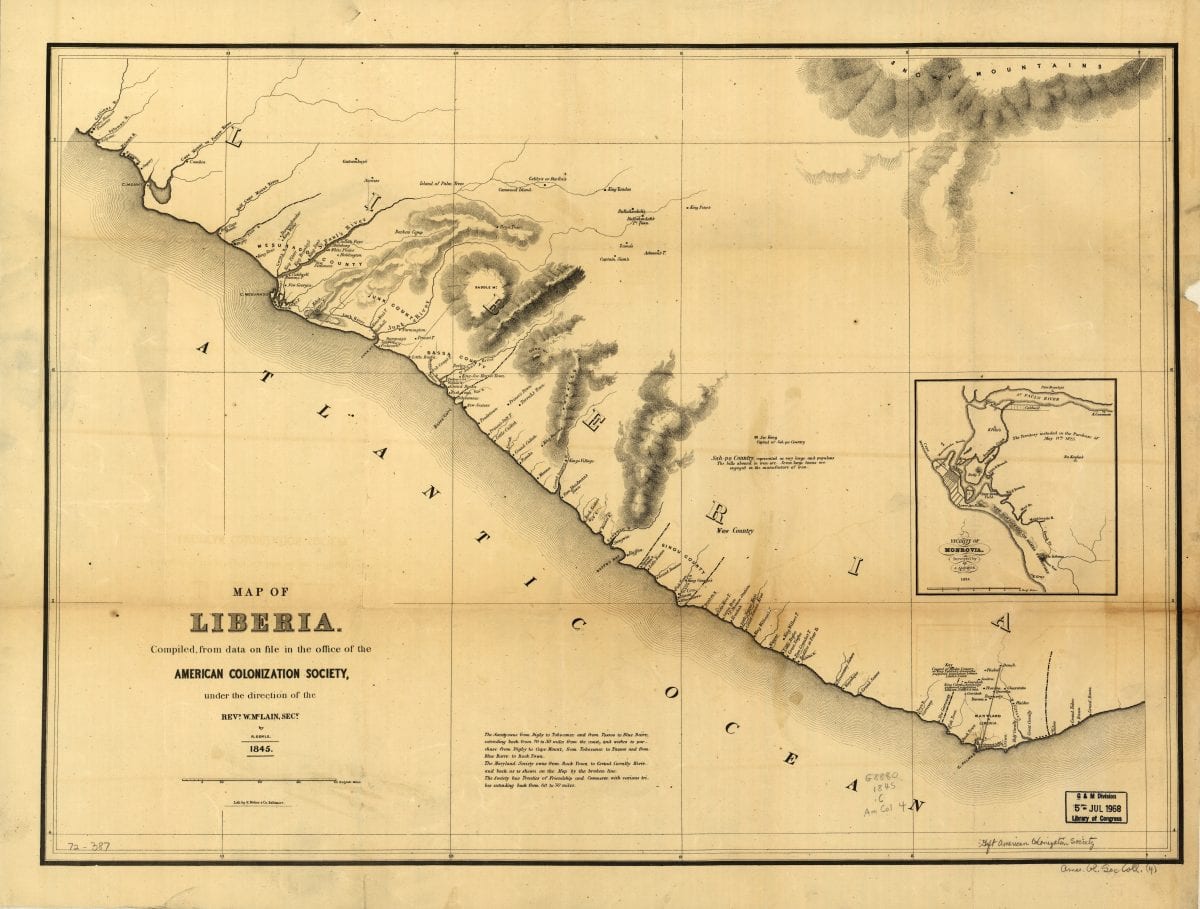

Five history graduate students—supervised by Martha Sandweiss (History) and Gabriel Swift (Librarian for Academic Programs, Special Collections)—are working in two teams. The first, comprised of Brian Wright, Poorvi Bellur, and Kate Carpenter, is transcribing diaries, journals, and scrapbooks from the University’s Western Americana collections. The second team, consisting of Kim Worthington and Mateusz Falkowski, is transcribing the extensive journals of Robert Wood Sawyer, Class of 1838, a seminary student who went to Liberia in 1841 as a missionary for the American Colonization Society.

A Nameless Author and a Lost Son

Our research into each journal’s author, context, and provenance has proven both rich and surprising. In fact, in transcribing the Western Americana team’s first journal, we confronted an archival mystery both utterly simple and endlessly complex: who wrote it? The author, an unnamed soldier posted at a U.S. Army fort in New Mexico during the Civil War, filled the journal with scattered musings of nostalgic afternoons in western Maryland, fiery political debates in antebellum Mississippi, and dreams of a “printing house” in San Francisco during the era of the gold rush.

What did these fragments add up to? After scouring census records, muster rolls, newspapers, legislative reports, and the correspondence of a certain Jesuit priest, we found our man: the itinerant printer, serial political commentator, and clerk to Kit Carson during the celebrity mountain man’s infamous 1863 campaigns against the Navajo, William Need.

What Need chose to jot down in his diary left a tantalizing trail of clues, just enough for our team to find him. And yet the full story—all of Need’s personal anxieties and entanglements, his role at that remote fort in New Mexico Territory, the existential war ripping America apart in those years—would only emerge with the benefit of accumulated archival records, historical expertise, and plenty of hindsight.

Finding Need offered an object lesson in the power of collective historical research. Wright, Bellur, and Carpenter worked with Sandweiss and Swift to link fragments from Need’s journal to related primary and secondary sources. Even isolated within our homes, thousands of miles apart, our team marshaled Princeton’s digital resources and material from dozens of archives to make a remarkable discovery.

We are now discussing how we might spread Need’s story, as well as narrate in more detail how our team solved the mystery of the unidentified journal. Our approach might take the form of a journal article, a digital humanities website, or another public exhibition. We were struck by Need’s extensive movements across the hemisphere, his shifting politics on the fate of American slavery, and his conflicted attitudes toward the many independent Native American tribes disrupting U.S. Army prerogatives in New Mexico Territory.

After completing the transcription of Need’s journal, the Western Americana team moved on to its second set of journals, written by a surveyor and Indian agent named Thomas Adams. Adams’ journeys through the northern Great Plains in the 1850s document contentious treaty negotiations between the U.S. government and numerous Indigenous groups. Adams also apparently had a son with an Indigenous Flathead woman in 1862. We are currently piecing together Adams’ life after his adventures out west.

We are also investigating whether a young man photographed with a Coastal Salish delegation in Washington, D.C. in 1884 may have been Adams’ son. This discovery would at once reveal a taboo secret in Adams’ relatively unknown personal life. But it would also help capture, within one dislocated family, the individual passions, conflicts, and predicaments at the heart of America’s nineteenth-century conquest of the continent.

A Missionary at All Costs

The project’s second team is busy transcribing the second journal of Robert Wood Sawyer, Class of 1838, which covers his final year at the College of New Jersey, time at the Princeton Theological Seminary, work and relationships in and around the town of Princeton, calling to missionary work “among the heathen,” marriage, and eventually journey to Africa and arrival in Monrovia (his life is briefly explored in this Princeton and Liberia article). These events precede Sawyer’s death in late 1843.

Sawyer was born in 1813 in Goshen, New York. He does not seem like a typical Princeton student. He presents a somewhat isolated figure, having a small circle of contact with fellow devotees while teaching or preaching to those on the social margins, such as older ladies in town. He spends most of his time in prayer, meditation, and study. He particularly aspires to master the original languages of the Bible. In one intriguing episode from Sawyer’s stay in Princeton, he agrees to tutor an African American servant and teach him to read, hoping that the experience will eventually improve his effectiveness as a missionary. The arrangement appears extraordinary for the place and time.

The journal offers a glimpse of how adherence to the strict work ethic of Presbyterianism and other Calvinistic values can shape one person’s life as well as the lives he touches. Until Sawyer steps on board the ship to Africa, the journal revolves around his spiritual progress and intellectual preparation for his missionary path. Interestingly, at no point does he clearly wish to work in a particular location or community. He simultaneously considers India, China, and Africa. He undertakes missionary efforts solely because of his strong faith and duty to fulfill God’s will, wherever He sends him. The realization of Sawyer’s wish comes and he departs for Africa, via Norfolk, on board the Saluda on October 6, 1841.

Notably, the journal reflects Sawyer’s singular worldview. The modern reader may be surprised, for example, at his absence of interest in the air of mystery and adventure associated with Africa at the time. His actions revolve wholly around the religious goal to convert the heathens and redeem their souls. Prior to his transatlantic journey, Sawyer never hints at any preparation for the missionary journey other than theological and spiritual. Still, attempts to compare Sawyer’s journal to the widely popular writings on Africa by the Victorian British explorers and missionaries such as David Livingstone, Sir Samuel White Baker, or Sir Henry Morton Stanley will always be unfair. It is important to remember that Sawyer’s journal was a deeply personal account, almost a record of his spiritual life, never meant for publication. In addition, the text is fairly poor from a literary point of view; Sawyer, for example, never goes back to previous entries to correct anything. His entries are not consistent either, with gaps sometimes spanning three or four months.

By the standards of contemporary American history, however, the silence of Sawyer’s journal may provoke more astonishment. His lack of engagement with any debates on slavery, colonization, and the “return” of black Americans to Africa is conspicuous, especially in the part of the journal after he learned that he would be going to Liberia.

While forgoing political commentaries or polemics, Sawyer’s journal remains a gem as regards the early history of American missionary efforts. It stands out as one of the earliest first-person accounts of a mission to Africa by an American, and as such deserves every bit of the attention of historians.

The team has so far transcribed roughly two-thirds of the journal. Sawyer and his wife have arrived in Africa and are about to start their work among local communities. We expect to continue working on the transcription. Upon completing this task, we intend to review the whole text, emendate previously dubious passages, and start footnoting the journal. Though Sawyer’s text centers on his own perspective, it contains many threads that we can expand to provide much-needed contextualization for the journal.

Conclusion

The musings within journals like that of Sawyer—and the journals as objects themselves—strike at the heart of a heated debate now underway amongst historians, archivists, and librarians: whose voices from the past populate our repositories and our stories? And how do these voices shape our understanding of our past and our present? Now more than ever, academic research requires constant communication, technological savvy, and intellectual self-awareness.

The Public Transcriptions Project will hopefully serve as an example of the value and potential of collaborative scholarship. Our teamwork has proven an exceptionally rewarding experience during the pandemic shutdown. The Project requires regular contact between fellow students and supervising faculty, rejuvenating the sense of Princeton’s intellectual community. Weekly meetings online, where all participants present the most recent progress, resemble a graduate seminar. Crucially, we agreed to hold these meetings on a regular basis at a set time during the week, which gives a certain structure to the otherwise disturbed academic life these days. The project, which heavily relies on the digitization efforts at the Firestone Library, also underscores the role that digital tools play in the humanities. The Project’s overall progress and individual discoveries—some particularly remarkable at such an early stage of our investigation—have shown that despite current challenges, important work can continue if planned and managed well.